George Thomas Heery Sr. was a giant in architecture, known as much for his inclusivity as for his industry innovations.

“He was an anti-racist. He lifted everybody up,” said George Heery Jr., who watched his father embrace the civil rights and women’s rights movements, and hire some of the first Black and female architects in the U.S.

“He was profoundly progressive,” said Merrill Elam, an Atlanta-based architect hired by Heery in 1969, when women comprised 3 percent of architects in the U.S., according to the American Institute of Architects. Elam went on to become one of the first female principals of an architect firm.

Heery, 93, died Jan. 21 at his Atlanta home, following a brief illness. The family plans a memorial service in the future at Oconee Hill Cemetery in Athens, Georgia.

He spent the day before he died watching the presidential inauguration. “In many ways, I think it was his dying wish to see the change in government,” said daughter Laura Heery. “He shared many values with Joe Biden.”

Born in Athens in 1927, to an architect and homemaker, he always knew he wanted to be an architect like his father, Wilmer Heery. He designed his first building at age 14 for one of his father’s customers. Following high school and two years in the U.S. Navy, Heery enrolled at the Georgia Institute of Technology, graduating in 1951. He had married the year before and began an architecture practice in the spare room of their home. It eventually becoming Heery International Inc., with 600 employees and offices around the world.

Heery was only 36 when his career was boosted by the building of Fulton County Stadium to attract the then-Milwaukee Braves, a project his company completed from design to construction in a record-breaking 17 months. He went on to design and manage construction of major league and collegiate stadiums and arenas across the U.S. — including Atlanta’s Georgia Dome —as well as major corporate and government projects around the world. His clients included Atlanta’s world-wide brands —The Coca-Cola Company, Lockheed, Delta Airlines. He headed design and construction of 999 Peachtree office building and The Wakefield luxury cooperative, as well as projects for Morehouse, Emory and Georgia State universities, Spelman College and Georgia Tech.

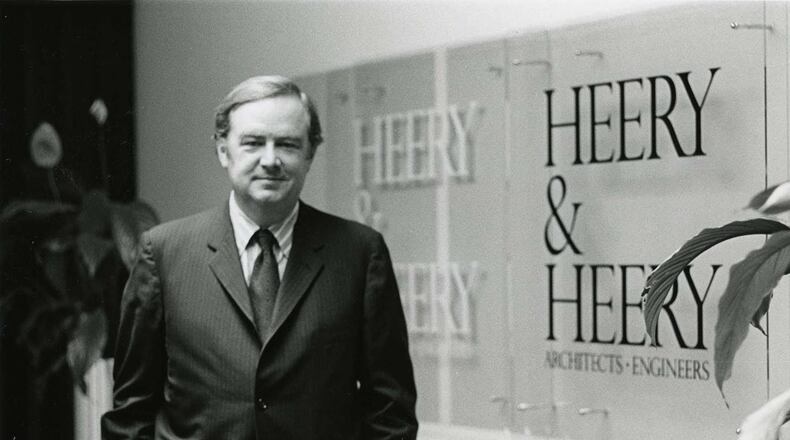

Credit: Rich Addicks

Credit: Rich Addicks

“The biggest names in business trusted George,” said former Atlanta Mayor Sam Massell.

Heery created better methods to get things done by controlling time, costs and risks, such as construction program management, that are followed by firms around the world.

The company was sold in 1986, when it was ranked 195 in Engineering News-Record’s Top 500 Design Firm list. Afterward, he and two children formed the Brookwood Group, where he continued to work daily until he was 88.

“There was no leisure for George, but it was all fun to him. He had more fun doing what he did than anyone I’ve ever known,” said Atlanta architect and longtime friend Walter Ennis Parker Jr., who directs the group of masters-level Construction Program Management courses Heery initiated at Georgia Tech.

Heery lived his beliefs on equality.

“George looked for talent — whoever, wherever, whatever that looked like,” said Elam.

He endorsed Andrew Young’s 1970 bid for Congress and served on the board of Spelman College. At home, he and his family hosted friends of various ethnicities, professions, and political views. He and his wife formed the Jazz 30 Club with 14 other couples, flying Black jazz musicians into Atlanta for private concerts. He surrounded his family with progressive thinkers.

In the 1990s, Heery started Metro Group, a watchdog organization, which held local government officials accountable for justice and fiscal responsibility. Using his expertise, the group called out in 2002, for instance, the multiple layers of politically connected consultants given contracts in the $5.2 billion Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport expansion as confusing, redundant and unnecessary.

“George founded this group as though it was his responsibility,” said Massell. “He felt Atlanta’s success and proper functioning was his duty.”

Heery’s children said their father, despite his position, treated everyone well. He would pause to ask taxi drivers about their lives.

“He really did celebrate everybody,” said George Heery Jr.

Survivors include his wife of 70 years, Maude Elizabeth “Betty” Heery; daughter Laura Heery of Atlanta, New York City, and Miami; sons Shepherd “Shep” Heery of Whitefish, Montana, and San Francisco;, and Neal Heery and George Heery Jr. of Atlanta; and seven grandchildren.

Memorials may be made to the George and Wilmer Heery Professorship Fund in the School of Architecture, College of Design, Georgia Institute of Technology, 760 Spring St., Suite 400, Atlanta, Georgia, 30308.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured