He received his orders in 1942. Franklyn Dailey would be the gunnery officer on the USS Edison, a destroyer. Ensign Dailey and his shipmates had no illusions: With a world at war, a world aflame, they would certainly sail into troubled waters.

But that is just one chapter in a story that stretched more than 10 decades and only ended March 19 in Milton, where Dailey died at 104. Yes, 104.

From his early days as a latchkey kid, before the term had been invented; to his training at the U.S. Naval Academy; to his deployment to fight in the Atlantic and Mediterranean; to his postwar work and research in manufacturing and technology; and to his final days when he led sing-alongs at a metro area senior-living home, Dailey — sailor, aviator, author and more — lived a life whose horizons stretched far as any ocean.

Add another descriptor: dad. With his wife, Marguerite, the couple had eight children.

Franklyn is predeceased by Marguerite Virginia Parker Dailey, and a son, Paul McGary Dailey. The seven surviving children and their spouses are Franklyn Edward III (Patricia), Michael Parker (Maureen), Philip Talbot (Sally), Elizabeth Valentin (Michael), John Lasher (Cindy), Thomas Ambrose (Frances) and Vincent Christopher (Naviza). Survivors also include 18 grandchildren, 27 great-grandchildren and two great-great-grandchildren.

Dailey’s death highlights time’s steady march among the ranks of those who served in that 1941-45 global conflict. In 2023, an estimated 119,000 American World War II veterans were alive. A year later, that number had dropped by almost half — 66,000.

In military and professional travels, Franklyn and his wife made a loving home in 16 sites before settling in Wilbraham, Massachusetts, for 45 years, and then retiring to Georgia to be close to family. Franklyn made friends at all of his stops in his childhood, military, civilian, married, religious and family life.

Franklyn Dailey was born Feb. 5, 1921, in Brockport, New York, to Franklin and Isabel Louise Dailey. By the time he was 10, the Great Depression had grabbed hold of America and wouldn’t let go. One lean year followed the next, forcing Franklyn’s mother to seek work. She found it — in New York City, more than 300 miles from home. Franklyn and his sister were on their own.

“He was basically alone in a giant house,” said son Michael Dailey, at 78 the second-oldest of the Dailey children. With the help of a friend, Franklyn learned to trap, skin and eat wildlife, selling pelts to help make ends meet.

But not all enterprises ended well. Once, Michael Dailey said, his dad caught a skunk before going to school. The nuns who ran the school took one whiff of their young scholar and sent him home to change clothes.

That may have been the only time that, as a student, he stunk.

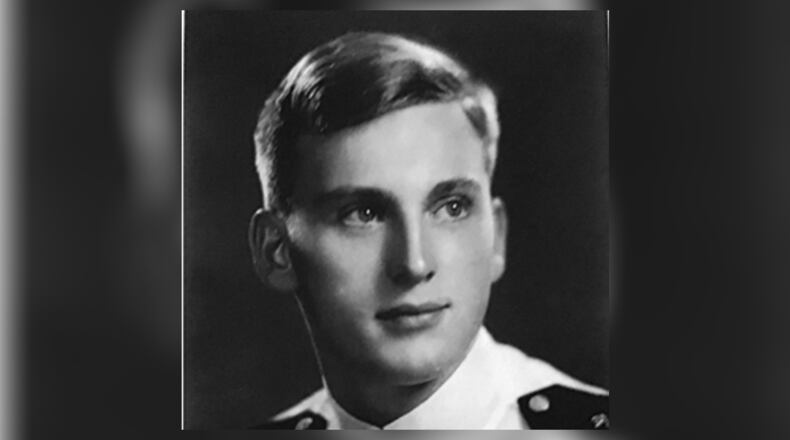

Young Dailey placed out of several high school classes and graduated at the age of 14. He worked for a few years at Kodak, in nearby Rochester, before applying to the U.S. Naval Academy. He entered in 1939. There, he accomplished the unthinkable: Midshipman Dailey scored a perfect grade on his navigational finals. The next year, he did it again.

Dailey earned a bachelor’s degree with distinction and later would get a postgraduate degree in electrical engineering, following that with a degree in applied physics.

In 1942, he became the gunnery officer on the USS Edison, a warship active in the Atlantic and Mediterranean. The destroyer served in campaigns from Casablanca to southern France, once firing so incessantly in battle that the ship’s barrels turned white-hot.

The Edison was also instrumental in forcing to the surface one of the Third Reich’s submarines — U-boats — that prowled the oceans. The Edison rescued 11 German sailors from the crippled U-73 as it emerged from the depths. Later, the U-boat’s captain asked Dailey why the ship fired on his sailors, Dailey had a quick reply: “Because you were shooting at us.”

In early 1944, the Edison returned to the U.S. for repair. Dailey took advantage of his shore leave. On April 1, 1944, at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City, he wed Marguerite Virginia Parker. That union lasted until her death on May 26, 2017.

In 1945, Adm. Henry Hewitt, commanding officer of the U.S. Navy’s 8th Fleet, commended the young gunnery officer for his service during the Edison’s invasion of southern France the previous year. By then, Dailey had eyes for something else — the sky.

He transferred back to the States and got his wings, all shiny gold. For the rest of his naval career, he piloted an array of aircraft. He patrolled the Aleutian Islands while eavesdropping on Soviet broadcasts. In another duty station, Dailey flew one airplane while using radio controls to operate another — an operation that presaged the use of drones in warfare.

Credit: Courtes

Credit: Courtes

It’s unfair to discuss his military life without mentioning that torpedo.

During a mid-1950s training exercise off the coast of California, two subs fired torpedoes in a test to determine the military’s capability to defend against biological weapons unleashed in an ocean attack. One vanished, lost not far from shore. Dailey’s job: find it. He may as well have been looking for a marble in a meadow.

“Did you ever find it?” Michael Dailey once asked his dad. “Hell no,” the elder Dailey replied.

Dailey left the Navy and shifted to the Naval Reserve, training on weekends. He reached the rank of captain before retiring in 1963.

The Dailey family settled in Massachusetts. Not everyone was pleased with dad’s choice, said Tom Dailey. At 67, Tom is the second youngest of the Dailey children.

The family home had a fine, big backyard, said Tom Dailey. The Dailey kids’ old man gave them a choice: pool or tennis court?

“Naturally, we all voted for a swimming pool,” Tom Dailey said. “And, of course, we got a tennis court.”

Franklyn Dailey was an avid tennis player.

Dailey the civilian focused his energy on engineering and planning. He worked in telecommunications, technology and plastics before going to Scott Graphics Inc. There, he helped invent updatable microfiche, a procedure that greatly enhanced how the photo-based document storage system could be used.

In 1976, he founded Image Technology and Application, a consulting business. His work captured the attention of federal officials, who tapped him to help advise preservation procedures for the National Archives.

He was busy at home, too. Dailey wrote “Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945,” “The Triumph of Instrument Flight: A Retrospective in the Century of U.S. Aviation” and “My Times with The Sisters and Other Events.”

In 2007, after decades in the Northeast, Marguerite and Franklyn Dailey moved to metro Atlanta to be closer to family members.

Dailey was a man of many talents, said Edith Ivey, who met the retired captain seven years ago at Mansions Independent Living in Alpharetta. He was fun, courteous, and …

“He had great legs for a man his age,” said Ivey, 95 and a retired actress. “We whistled at him all the time.”

Dailey had a habit of bursting into song at mealtimes. Within moments, he had the entire dining room joining the chorus.

“When you hear ‘The White Cliffs of Dover’ being sung when you’re having dessert, that’s fun,” Ivey said.

When his fading memory required Dailey to move to other accommodations, the good folks of the Mansions offered him a send-off only a sailor could fully appreciate.

“All the rooms, they came out and sang ‘Anchors Aweigh’” as he left the building, Ivey said. “He was everything you’d want to be if you lived that long.

“We miss him terribly.”

The funeral will be held at Saint Peter Chanel church in Roswell on Friday at 10:30 a.m. Burial and graveside ceremony will be held at Gate of Heaven cemetery in Springfield, Massachusetts, on April 11 at 1 p.m.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured