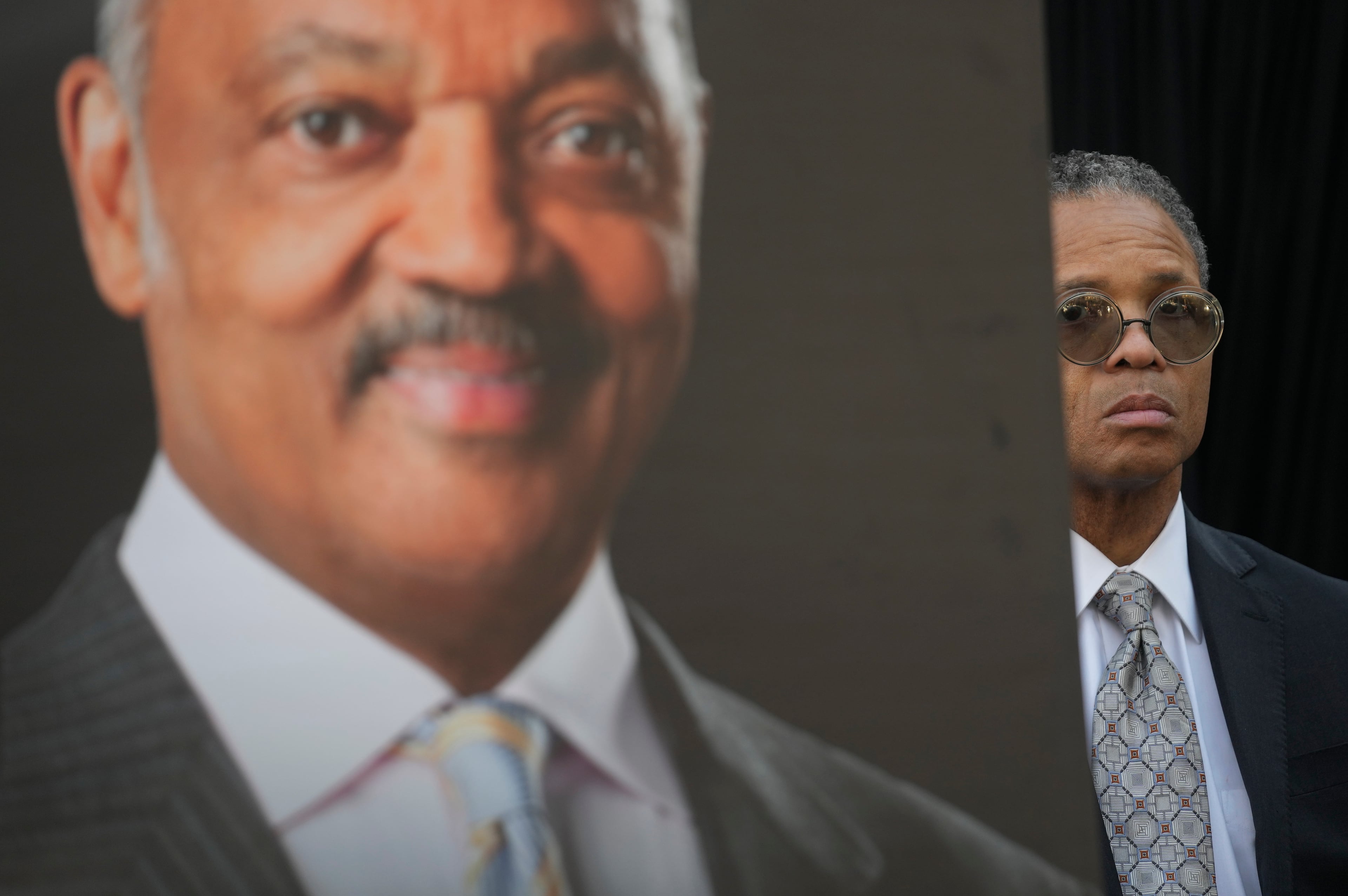

Dr. Lee Shelton blazed paths from Marines to hospitals

In 2023, officials from the Montford Point Marine Association tracked down Lee Shelton to help award him a Congressional Gold Medal, one of the highest awards given to a civilian or a group. The medal honored his service as a Montford Point Marine — the first African Americans who were allowed to enlist in the U.S. Marine Corps in 1941.

It was one of many firsts for Shelton.

“He was never a sharer,” said his older daughter Marva Shelton. “He didn’t talk about his time in the Marine Corps. We didn’t know much about it until they showed up here with the medal.”

Dr. Lee Raymond Shelton became well-known among medical circles as an excellent surgeon, a dedicated physician and a civil rights advocate. On Sept. 7, he died at home at age 96, not far from the hospital where he worked for more than 20 years. His daughter Marva said he told her he was ready to go, and after receiving Communion at home, he did.

Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, he was the oldest of the three sons of Mabel and Lee Shelton, who raised him in Wilmington, North Carolina, where he learned to play the trumpet. After high school came the Marines. After returning home, he used the G.I. Bill to attend Howard University.

While in college, Lee Shelton would form musical groups and find paying gigs to supplement his G.I. Bill college funds Band leader Fletcher Henderson tried to recruit him, Marva Shelton said, but he stayed in school. All three brothers attended Howard University and completed medical school.

Later, at parties and galas featuring live music, Lee Shelton usually came with his trumpet mouthpiece in a pocket, and if asked, was happy to join the band.

After finishing at Howard, he did a residency in general surgery at the Tuskegee Veterans Administration Hospital in Alabama. While there, he participated in civil rights boycotts in nearby Montgomery in the late 1950s. Shelton received further training at Hughes Spalding Hospital in Atlanta, where he and his wife Deloris and their children relocated.

Marva Shelton said her father desegregated the staff of Holy Family Hospital, which had been started in the 1940s by Catholic nuns wishing to help Black families. It was later renamed Southwest Community Hospital. With surgery becoming specialized, Shelton went back to school and became an emergency medicine doctor, running Southwest’s emergency room. The hospital closed in 2009.

The 1960s saw Lee Shelton involved in several significant firsts. In 1962, he was one of the first two African American doctors admitted to the Fulton County Medical Society. In 1963, Deloris and he took a bold step to eat dinner at Herren’s, a downtown power-broker restaurant on Luckie Street that was the first Atlanta establishment to serve African Americans.

“He did say that was a very pleasant evening and that was the best steak dinner he ever had,” Marva Shelton says.

In 1964, Southwest Community Hospital became the first in the Southeast to allow Black and white doctors to work together.

When Deloris became plagued with medical problems, Lee Shelton became her caregiver. Initially, he didn’t tell the children the full extent of their mother’s ailments, including that she had Alzheimer’s, Marva says. “He was a real trooper.”

Ever the private person, he had made arrangements to give both his and his wife’s body to science, “so we wouldn’t have to worry about it,” his daughter says.

In addition to his daughter Marva, Lee Shelton is survived by daughters Fawn and Gia, son Raymond, three grandchildren and five great grandchildren. A celebration of life will be held later this fall.