5 days in America: Violent death, sacred remembrance

I, too, am America.

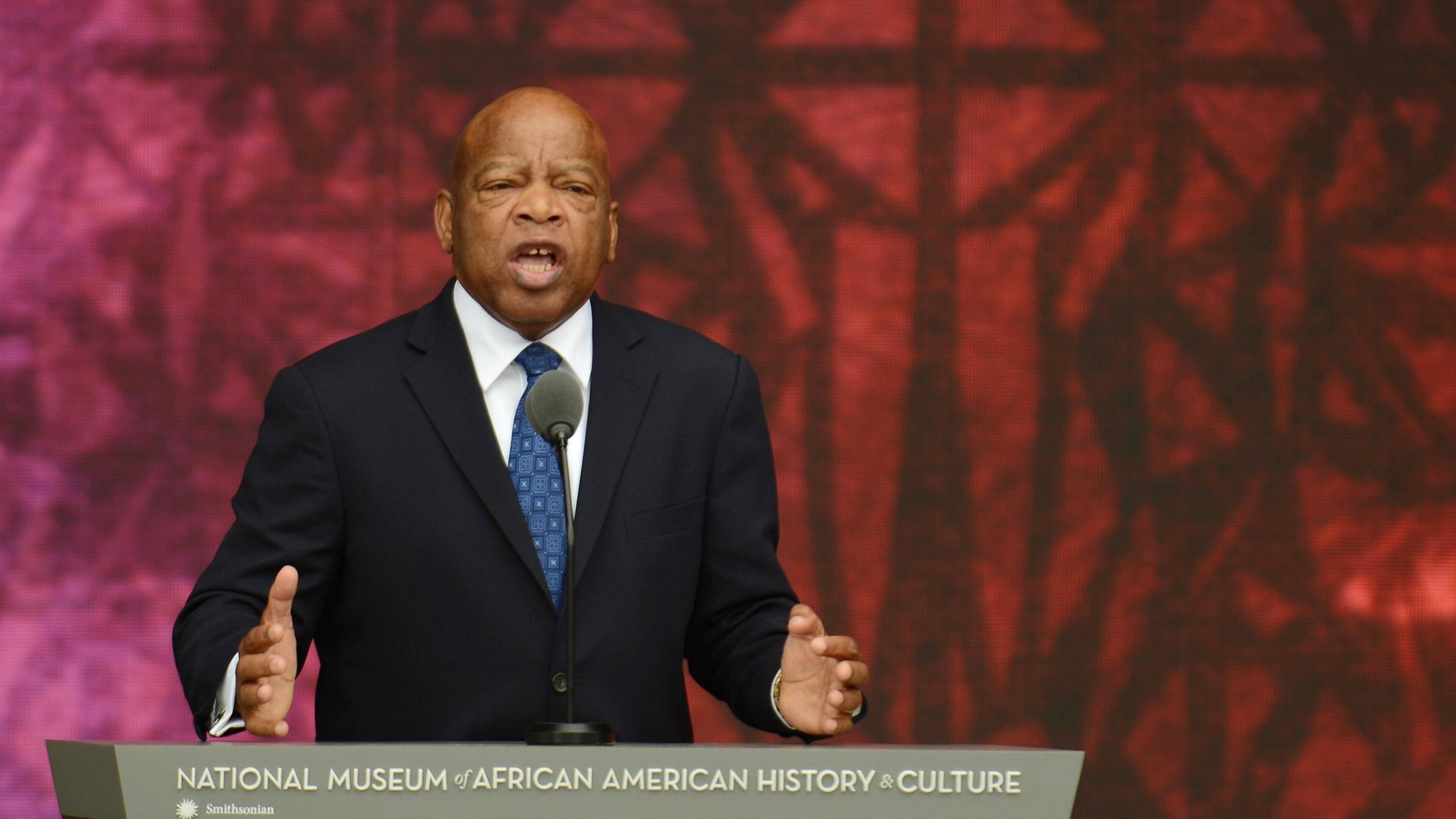

On Sunday, soon after I walked for the first time into the new and glorious National Museum of African American History and Culture, I was hit with those last four words of Langston Hughes’ 1926 classic poem, “I, too,” in large letters on the wall.

Perhaps never in the history of this country have Hughes’ words spoken so loudly.

Barack Obama, our country’s first black president, said the new museum “helps to tell a richer and fuller story of who we are.”

“By knowing this other story we better understand ourselves and each other,” Obama told us. “It binds us together. It reaffirms that all of us are America, that African-American history is not somehow separate from our larger American story. It is central to the American story.”

And that story continues to be complex — and painful.

Just days before the museum opened, another black man — this one in Charlotte — died at the hands of police officers, adding to a national narrative that only seems like an epidemic because we all have camera phones now.

Four days after the death of Keith L. Scott, I joined thousands of others on the National Mall for the opening of the Smithsonian’s latest museum. It chronicles the breadth of African-American struggle and triumph from the slave ships through the election of Obama.

I stood on the Mall and listened to Obama and watched the daughter of a Mississippi slave ring a bell to officially open the museum. There was hardly a dry eye in the crowd. That night, in that same spot, I was in the middle of a delirious and multicultural mob of people listening to my two favorite hip-hop groups – The Roots and Public Enemy.

I was working, but the weekend was great. What a difference a few days make.

It is never a good thing to get a text from your boss early in the morning. But as I was literally on my way to Washington to cover the opening of the museum, I was told that I needed to go to Charlotte.

I wanted to get to Washington early to get the lay of the land, work in the bureau there and do a couple of stories. I went to high school with the museum’s lead architect and wanted to do a story on her.

But I knew why I was being called. Sure, North Carolina is my home state, but I was not in the mood to return there to cover something that has happened over and over and over again for the past 400 years — a black man killed by an authority figure.

So instead of flying to Washington to cover a celebration, I was flying to Charlotte to cover a riot.

I have been down this path before.

The early morning text to go to Ferguson for Michael Brown.

The early morning text to go to Charleston for Walter Scott.

Dallas for the police shootings. Orlando for the nightclub massacre.

Dispatched back to Charleston for the Mother Emanuel murders of nine churchgoers.

I arrived in Charlotte Wednesday afternoon and went directly to the spot where Keith Scott died, in the visitors space of an otherwise quiet and unremarkable apartment complex. But as a makeshift memorial grew, so did tensions. All across town, groups were gathering to tell the city and police department that they had had enough.

So hundreds of people marched, a tactic that fighters for equality and civil rights have employed for decades. But this was not to be the sort of peaceful resistance that Martin Luther King Jr. pursued so effectively. In short order the demonstrations became violent.

Vandals roamed the streets of downtown, breaking windows and looting drug stores and gift shops.

Police in riot gear lobbed canisters of tear gas, setting off stampede-like retreats. Demonstrators threw them back.

As my eyes burned with the gas that I had become so familiar with in Ferguson, as I stumbled over men and women crying and vomiting in the street, as I watched other journalists get attacked, I thought back to Missouri and wondered whether anything could possibly be worse than Ferguson.

Then a gunshot rang out and a man named Justin Carr was dead.

For no reason.

Dead because he came to protest the death of another black man.

That night might have been worse, but the violence subsided. By Thursday, demonstrators still roamed the streets, but it was calmer to the point where you hardly saw police in riot gear at all – replaced by National Guardsmen, who spent more time shaking hands than waving guns.

Thankfully, that was my cue to leave. I made it to Washington by Friday afternoon.

Just in time for a reception at the convention center hosted by Morehouse College.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Two days after sweating and running for my life and eating lousy food, I was in a nice suit eating risotto with giants like Andrew Young, David Satcher and Louis Sullivan. The contrast was striking. Here I was with 500 college-educated black men and women — many from Atlanta — in town to celebrate, while in many of our cities and towns black men are dying in the streets.

But everything in Washington told a different story, wrapped up in what was happening in Charlotte. Washington was about acknowledging our greatness, while understanding the struggle.

I can’t fully put into words how it felt to enter the museum to see remnants of a slave ship and a slab of rocks that slaves would stand on to be auctioned off. But as you wind your way up the museum, you see the black people who fought against slavery, the early politicians, the soldiers, the musicians, the institutions.

But there are the reminders. The Klan robes. The “whites only” signs. The brittle casket of Emmett Till, whose 1955 murder launched the modern civil rights movement.

The killing of Keith Scott — police are still investigating the shooting — and Justin Carr are reminders, too

Reminders that while we celebrate how strong, beautiful and black we are as a people and a country, we still have a long way to go. This wondrous new museum is America. But Charlotte and Ferguson and Tulsa are America, too.

I will remain on the lookout for early morning texts.

On a side note, Flavor Flav is sitting with me in the airport. The Public Enemy hype man is still complaining about never getting an invitation to the White House from Obama. That’s progress.

Tomorrow,

I’ll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody’ll dare

Say to me,

“Eat in the kitchen,”

Then.

Besides,

They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America.