Inflation 101: Here’s why you’re paying more for everything

It’s not your imagination.

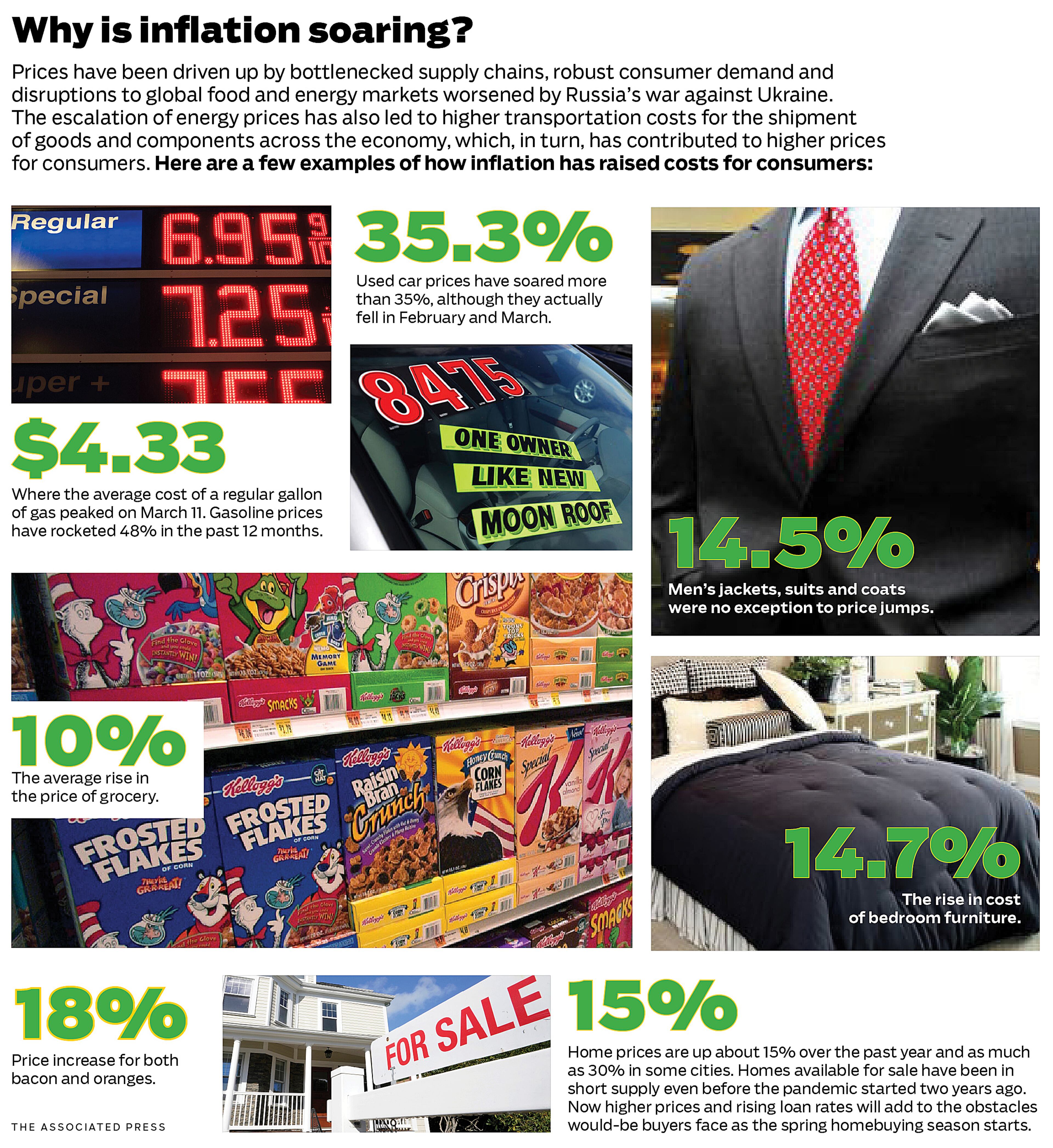

Everything from a loaf of bread to a gallon of gas has skyrocketed in price over the past year.

Airline tickets are up 24%, men’s suits nearly 15%, bacon 18%. Energy costs 32%.

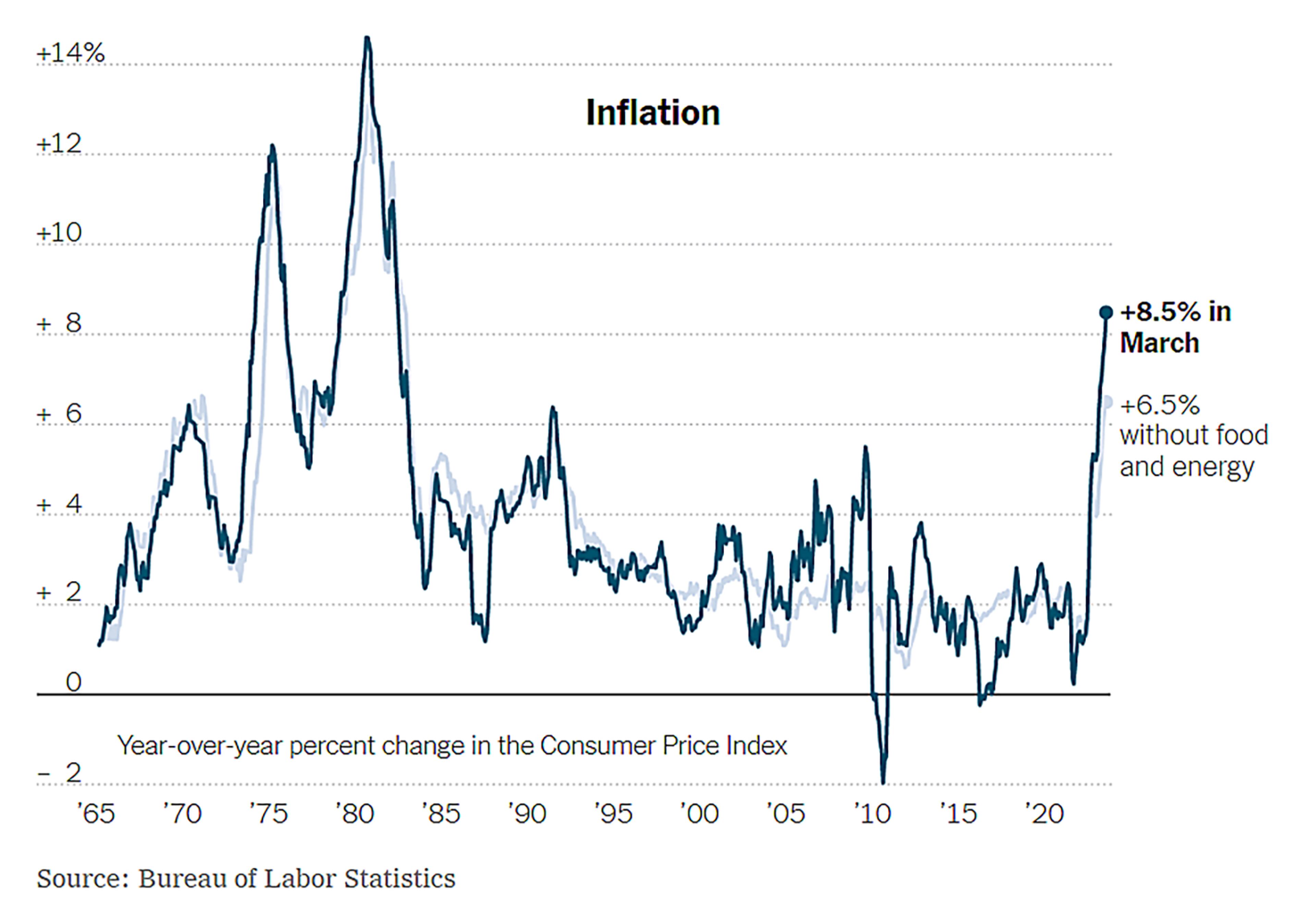

Inflation soared over the past year at its fastest pace in more than 40 years, the Labor Department reported this week.

For the 12 months that ended in March, consumer prices rocketed 8.5%. That was the fastest year-over-year jump since 1981, far surpassing February’s mark of 7.9%, itself a 40-year high.

Costs for food, gasoline, housing and other necessities are squeezing American consumers and wiping out pay raises that many have received.

Even core prices — which are other costs that do not include food and energy — climbed 6.5 percent over the year through March, up from 6.4 percent in the year through February.

When did all this begin?

Inflation, which had been largely under control for four decades, began to accelerate last spring as the U.S. and global economies rebounded with unexpected speed and strength from the brief but devastating coronavirus recession that began in the spring of 2020.

The recovery, fueled by huge infusions of government spending and super-low interest rates, caught businesses by surprise, forcing them to scramble to meet surging customer demand. Factories, ports and freight yards struggled to keep up, leading to chronic shipping delays and ultimately the ballooning of prices we are seeing today.

Who’s to blame?

Critics blamed, in part, President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package, with its $1,400 checks to most households, for overheating an economy that was already sizzling on its own. Many others argued that the Fed kept rates near zero far too long, lending fuel to runaway spending and inflated prices in stocks, homes and other assets.

A closer look

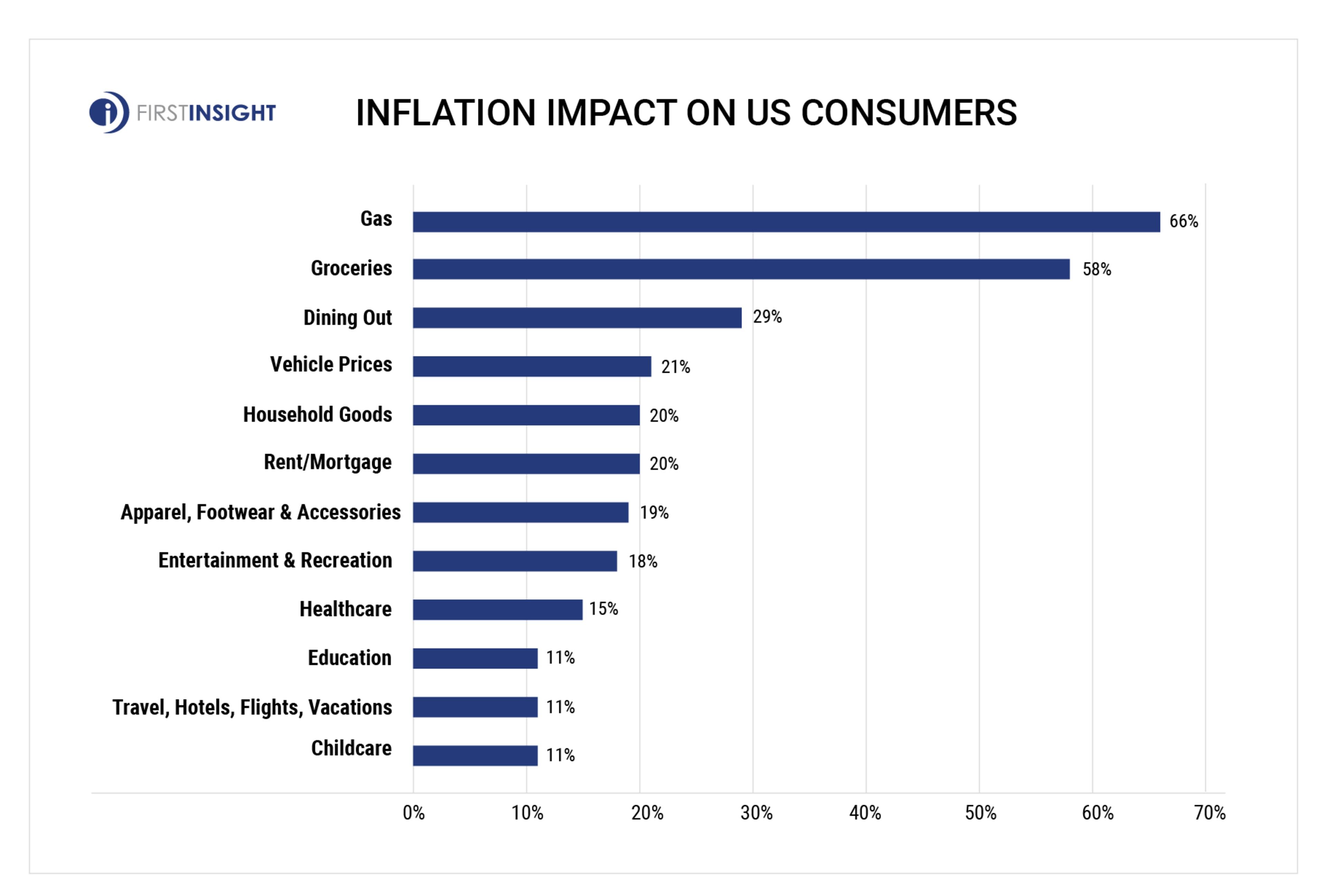

Prices were 8.5% higher in March than a year earlier. The following graphic is a look at the rise in year-over-year inflation, and which categories are doing the most to drive it.

According to one of the latest studies detailing the impacts of inflation on consumer spending, the top twelve categories affecting consumers' daily lives the most include:

- Gas

- Groceries

- Dining

- Vehicle Prices

- Household Goods

- Rent/Mortgage

- Apparel, Footwear & Accessories

- Entertainment & Recreation

- Healthcare

- Education

- Travel, Hotels, Flights, Vacations

- Childcare

Passing costs on to customers

Amazon.com announced this week that it will add a 5% “fuel and inflation surcharge” to fees it charges third-party sellers who use the retailer’s fulfillment services as the company faces rising costs.

The company said in an announcement on its website that the added fees, which will take effect on April 28, are “subject to change” and will apply to both apparel and non-apparel items.

The turn to such measures by corporations like Amazon boils down to simple economics: with demand up and supplies down, costs will predictably rise. But companies find that they can easily pass along the higher costs in the form of higher prices to consumers, many of whom have managed to pile up extra savings during the pandemic.

How did we get here?

When the pandemic paralyzed the economy in the spring of 2020 and lockdowns kicked in, businesses closed or cut hours and consumers stayed home as a health precaution, employers slashed a breathtaking 22 million jobs. Economic output plunged at a record-shattering 31% annual rate in 2020′s April-June quarter.

Everyone braced for more misery. Companies cut investment and postponed restocking. A brutal recession ensued.

But instead of sinking into a prolonged downturn, the economy staged an unexpectedly rousing recovery, fueled by vast infusions of government aid and emergency intervention by the Fed, which slashed rates, among other things. By spring of last year, the rollout of vaccines had emboldened consumers to return to restaurants, bars, shops, airports and entertainment venues.

Suddenly, businesses had to scramble to meet demand. They couldn’t hire fast enough to fill job openings or buy enough supplies to meet customer orders. As business roared back, ports and freight yards couldn’t handle the traffic. Global supply chains seized up.

With demand up and supplies down, costs jumped. And companies found that they could pass along those higher costs in the form of higher prices to consumers, many of whom had managed to pile up savings during the pandemic.

Why it matters?

Many Americans have been receiving pay increases, but the pace of inflation has more than wiped out those gains for most people. In February, after accounting for inflation, average hourly wages fell 2.5% from a year earlier. It was the 11th straight monthly drop in inflation-adjusted wages.

Did anyone see this coming?

The Federal Reserve never anticipated inflation this severe or persistent. Back in December 2020, the Fed’s policymakers had forecast that consumer inflation would stay below their 2% annual target and end 2021 at around 1.8%. Yet after having been merely an afterthought for decades, high inflation reasserted itself last year with brutal speed. In February 2021, the government’s consumer price index was running just 1.7% above its level a year earlier. From there, the year-over-year increases accelerated — 2.6% in March, 4.2% in April, 5% in May, 5.4% in June. By October, the figure was 6.2%, by November 6.8%, by December 7%.

How long will this last?

Elevated consumer price inflation could endure as long as companies struggle to keep up with consumers’ demand for goods and services. A recovering job market — employers added a record 6.7 million jobs last year and are adding 560,000 a month so far this year — means that Americans as a whole can continue to splurge on everything from lawn furniture to electronics. Many economists foresee inflation staying well above the Fed’s 2% annual target this year. But relief from higher prices might be coming. Jammed-up supply chains are beginning to show some signs of improvement, at least in some industries. The Fed’s pivot away from easy-money policies toward an anti-inflationary policy could eventually reduce consumer demand. There will be no repeat of last year’s COVID relief checks from Washington. Inflation itself is eroding purchasing power and might force some consumers to shave spending.

Is there any relief in sight?

President Joe Biden has announced he’ll suspend a federal rule and allow the sale of higher-ethanol gasoline this summer, trying to tamp down prices at the pump that have spiked during Russia’s war in Ukraine. Most gasoline sold in the U.S. is blended with 10% ethanol. The Environmental Protection Agency will issue an emergency waiver to allow widespread sale of a 15% ethanol blend that is usually prohibited between June 1 and Sept. 15 because of concerns that it adds to smog in high temperatures. Senior Biden administration officials said the action will save drivers an average of 10 cents per gallon, but at just 2,300 gas stations. Those stations are mostly in the Midwest and the South, including Texas, according to industry groups.

What’s next?

Measures of inflation will likely worsen in the coming months because recent reports don’t reflect the consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which began on Feb. 24. The latest evidence of accelerating prices will solidify expectations that the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates aggressively in the coming months to try to slow borrowing and spending and tame inflation. The financial markets now foresee much steeper rate hikes this year than Fed officials had signaled as recently as last month. The overall economy is healthy, with a robust job market and extremely low unemployment. But many economists say they worry that the Fed’s steady credit tightening will cause an economic downturn.

Edited and compiled by ArLuther Lee for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.