At 5:07 p.m. Tuesday, the youngest of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s children let out a virtual cry of deliverance.

“Whew,” Bernice King wrote on Twitter. “I can now take a breath.”

Exactly five minutes earlier, a jury in Minneapolis had announced its verdict in the trial of former police officer Derek Chauvin: guilty, on all counts, in the killing of George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man. His death stirred massive protests and inspired a reckoning with the nation’s history of institutional racism.

Across Atlanta and the nation, King’s relief was echoed at informal memorials to Floyd, in social media posts, and in conversations in barrooms and living rooms alike. A measure of often-elusive justice been served in the death of a Black person at the hands of a white police officer, and a reprise of the sometimes destructive unrest that followed Floyd’s death appeared to have been averted.

“There would’ve been rioting in the streets, no question about it” had there been an acquittal, said Kendric Smith, who watched the verdict announced at Manuel’s Tavern in Atlanta.

Manuel’s patron Sheila Bailey called the guilty verdicts an affirmation of the American judicial system. Any other outcome, Bailey said, would have raised doubts about ever holding police accountable.

“I was so glad they found him guilty on all counts,” she said. “It leaves no room for doubt.”

At a mural honoring Floyd on Atlanta’s Edgewood Avenue, civil rights activist Porch’se Miller called Tuesday “a good day for Black America.”

“We needed this win so bad,” she said.

Credit: AJC staff photo

Credit: AJC staff photo

But for many, jubilation over the verdict was tempered by the losses of Floyd and others killed by police violence.

“Finally, we’re getting some type of justice,” said Jamiliah Robinson, a mental health therapist. But “they’re still going to kill Black people. It’s been happening for hundreds of years now, and I don’t think much is really going to change.”

Floyd’s death — and Chauvin’s trial — brought unprecedented attention to killings by police in America. In Atlanta, thousands of protesters marched in the streets last year, some for months, and confrontations with police officers sometimes turned ugly. At the state Capitol last spring, officers fired tear gas and rubber bullets at protesters, and elsewhere in the city, police in riot gear cleared the streets when nightly curfews took effect.

The Atlanta Police Department was criticized both for not protecting property from looting and for using excessive force on demonstrators. Six officers faced criminal charges after pulling two college students out of their car near a downtown protest.

Then, 18 days after Floyd’s death, an Atlanta officer shot and killed 27-year-old Rayshard Brooks after a scuffle in the parking lot of a Wendy’s restaurant south of downtown. More protests erupted, demonstrators set fire to the Wendy’s, and an 8-year-old girl, Secoriea Turner, died when shots were fired into her mother’s car.

MORE: Rayshard Brooks’ final 41 minutes

Suspects in Secoriea Turner shooting remain at large

Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, like numerous other political leaders, issued a statement Tuesday celebrating the verdict in Minneapolis. She did not mention the unrest that roiled Atlanta after Floyd and Brooks died.

“While I am grateful that the verdict is guilty on all three counts, there is no verdict or punishment that will bring George Floyd back to his family,” Bottoms’ statement said. “As tragedies have propelled our nation into a level of needed consciousness and action in the past, it is my sincere hope that the tragic death of George Floyd will forever be our reminder that the work towards reform, healing and reconciliation is not a one-time event.”

For some, the Chauvin verdict brought to mind another trial. In April 1992, a California jury acquitted Los Angeles police officers charged with beating motorist Rodney King after a high-speed chase.

Said Sewell was a Morehouse College senior at the time and joined a march from the Atlanta University Center to the state Capitol to protest the verdicts in the King case. On Tuesday, Sewell, now an educator at the center, watched with “my stomach in knots,” hoping for a different result.

“I’m saddened that ... even though we saw a man killed on television, I was still worried that justice may not be as blind as it should be,” said Sewell, director of the center’s division of academic affairs, sponsored research and student success. “I’m overjoyed that justice was served, but saddened that we were worried it might not have been this way as it has been in previous cases. We still have a lot of work to do.”

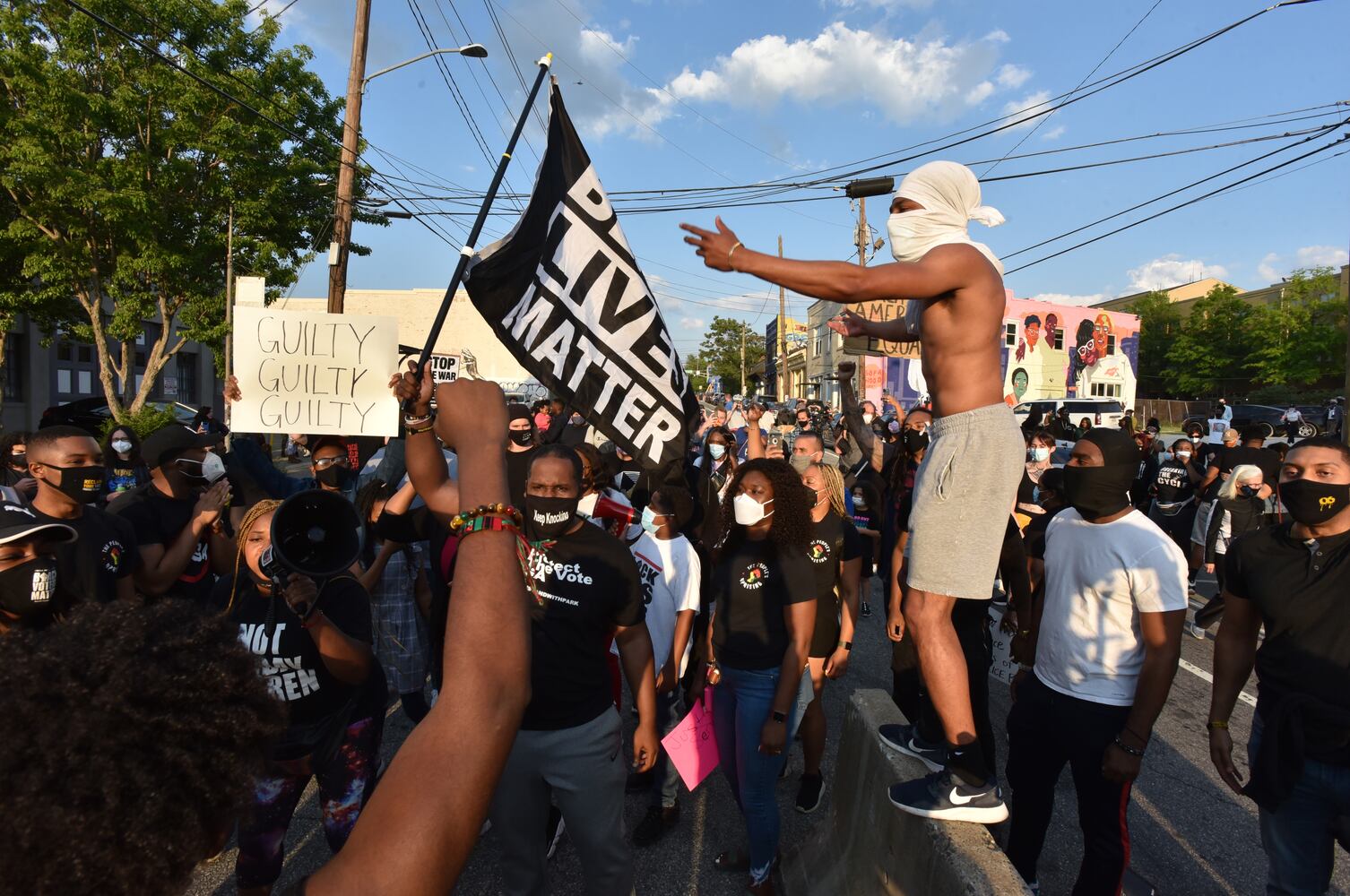

As news spread of the verdict on Tuesday, several dozen people gathered at the Floyd mural, preparing to march to Centennial Olympic Park.

“Guilty, guilty, guilty,” the marchers chanted. Jerome Trammel, a television producer, arrived at the park holding a sign that read, “Jail Killer Cops Now.” Onlookers in cars or buildings along the procession held up fists in solidarity or recorded the marchers on their phones.

“We were outside for 150 days” protesting after Floyd died, Atlanta attorney Gerald Griggs told the marchers. “We didn’t just march for George,” but also for Brooks and others killed by police, he said. He urged Congress to pass legislation to hold police accountable.

“This isn’t about a few bad apples,” Griggs said. “The system has a problem.”

Marcher Sugga Myrick, said the video that showed Chauvin pinning Floyd’s neck to the pavement for more than nine minutes before he died turned her stomach. A retired nursing assistant, Myrick said a stiff sentence for Chauvin, who faces as much as 40 years in prison, might cause other officers to take more care with the lives of Black people.

“I hope they don’t just give him a slap on the wrist,” Myrick said. “I want the max.”

For many at the Floyd mural, the verdict felt personal. Melodee Lovett said one of her friends is the sister of Rayshard Brooks.

“This is just the beginning,” she said of the Chauvin verdict. Still, “it feels like a weight has been lifted off my shoulders.”

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Staff writers J.D. Capelouto, Bill Rankin, Chris Joyner, Tyler Estep, Ernie Suggs, Sheila Poole, Kristal Dixon, Wilborn P. Nobles III, Arielle Kass, Christian Boone and Tia Mitchell contributed reporting.

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured