Black Marine Archeologists

Hundreds of sunken slave ships are scattered across the floors of the Atlantic Ocean. Many of them never to be seen again.

But Diving With a Purpose, a group of predominantly Black divers, has been on a quest to document and research slave wrecks salvaged from the deep to learn more about the Middle Passage. While DWP as a group has concentrated its efforts on one slave ship, its members have helped research shipwrecks across the globe.

Kamau Sadiki, a retired Washington, D.C. engineer, is one of DWP’s most active divers and instructors. He has participated in over 20 dives, some with DWP and some with other organizations. He says it can be a unique encounter that reconnects you to your roots.

Sadiki says he had his first such spiritual experience several years ago while on a mission to find the Sao Jose Paquete de Africa, a Portuguese slave ship that crashed and sank off the coast of Cape Town, South Africa in 1794. More than 200 enslaved people died when it capsized.

When Sadiki and his crew spotted a piece of the wreckage entrapped on a huge bed of rocks, he realized he was on hallowed grounds.

“I just remember approaching that piece of wood, reaching out and touching it. And almost instantaneously I could hear the screams and crashing waters, the horror, pain and suffering that went on,” he told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

36,000 voyages across Atlantic

There were more than 36,000 voyages across the Atlantic between 1514 and 1866 that “forcibly transported” nearly 12.5 million enslaved Africans to the New World, according to Harvard University’s Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade database.

No one knows for sure, but scholars estimate between 500 and 1,000 slave ships sank during the tortuous journey. Only five sunken slave vessels have been discovered. The Sao Jose was the first salvaged vessel that sank while slaves were on board.

As many as 2 million enslaved Africans died during the Middle Passage, the perilous stretch of the slave trade when ships sailed across the Atlantic, according to researchers.

Divers have recovered shackles, iron bilboes and slave pens used to imprison captives during the voyages, and other artifacts that crystallize how enslaved Africans were stowed beneath deck in the hulls of ships as cargo.

“It’s critically important for us to connect directly to these stories,” Sadiki said. “Bring these stories from our ancestors out into the public square and talk about it.

“If we don’t do that, we’re going to always be wandering around lost and disconnected,” he added.

Adventure in the Florida Keys

DWP was formed in 2005 and has spent nearly two decades searching for the elusive Guerrero, an outlawed Spanish slave ship that sank in the Florida Keys while being chased by the British Navy in 1827. Forty-one enslaved Africans on board the Guerrero died when it went down.

DWP’s conquests are chronicled in a six-week National Geographic podcast series called Into the Depths that debuted this month.

In 2020, DWP was featured heavily on Enslaved, a six-part docuseries hosted by Samuel L. Jackson that focused on the 400-year slave trade.

“Documenting these ships has its own history. And each ship has its own story,” said Diving With a Purpose co-founder Ken Stewart. “I think now is a critical time in this country’s history because they’re trying to change the narrative. That our ancestors who were enslaved, that they were immigrants and came here willingly. We know that’s not true.”

The Origin Story

Stewart and former Biscayne National Park marine archeologist Brenda Lanzendorf founded DWP together with the mission to find the Guerrero.

Lanzendorf also said she knew the site of the sunken slave ship inside the national park just south of Miami. According to Stewart, she pledged to train DWP divers how to document shipwrecks and was preparing to take them.

“She always said that when she thought we were ready, she would take us to the site of the Guerrero and let us be the first people to document it,” Stewart said.

But Lanzendorf died in 2008 after a six-month bout with cancer. She never told Stewart and company where the Guerrero was.

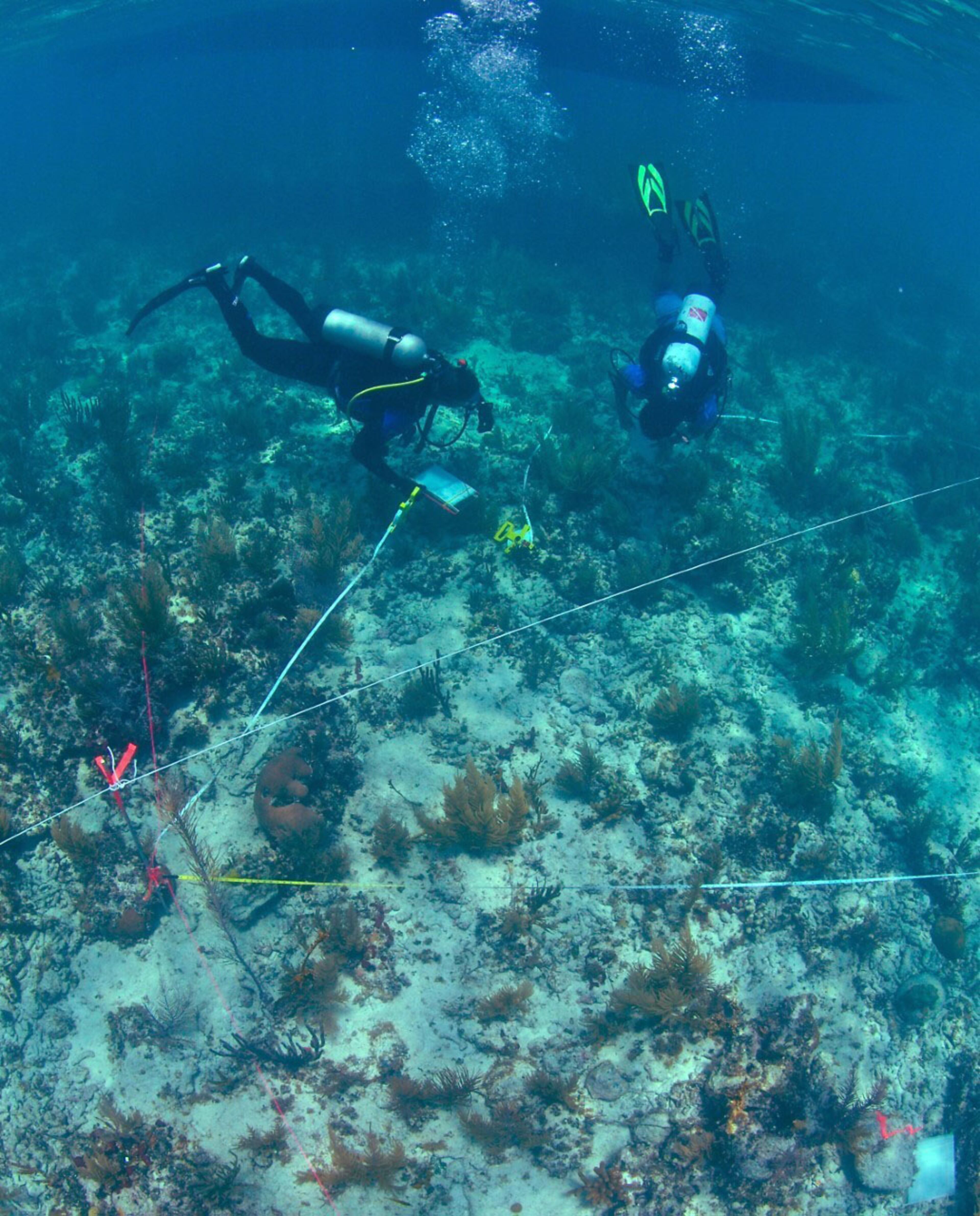

Each summer, DWP meets at a marine sanctuary in Key Largo for an intense week of marine archeology training offered to veteran divers. The group’s flagship is a summer diving camp at Biscayne National Park that teaches divers between 16 and 23 underwater archeology.

DWP has also partnered with researchers from the Mel Fisher Maritime Museum, who think the Guerrero’s in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary about 150 miles south of Biscayne National Park.

Corey Malcom, the museum’s director of archeology, suspects parts of the ship have likely been reduced to scattered pieces of debris at this point. “That’s what we’re dealing with., Malcolm said

In addition to diving for slave wrecks, another of DWP’s primary focuses is preserving the ocean’s natural habitat.

Kramer Wimberly, a diver with more than 35 years of experience, speaks passionately when describing the “delicately balanced ecosystem” that exists underwater. He leads DWP’s coral reef research and restoration program, which shows students how to observe and document the condition of the ecosystem.

Coral reefs cover less than 1% of the ocean floor but are responsible for producing at least half the oxygen on the planet, according to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Ecologists say reef habitats have shrunk an estimated 30%-50% since the 1980s and could disappear in the next 20 years.

“There is no more important thing to do today, in my estimation, than addressing the issues of the health of the coral reef ecosystem,” Wimberly said. “It’s in decline. It’s dying. And we’re doing things to kill it.”