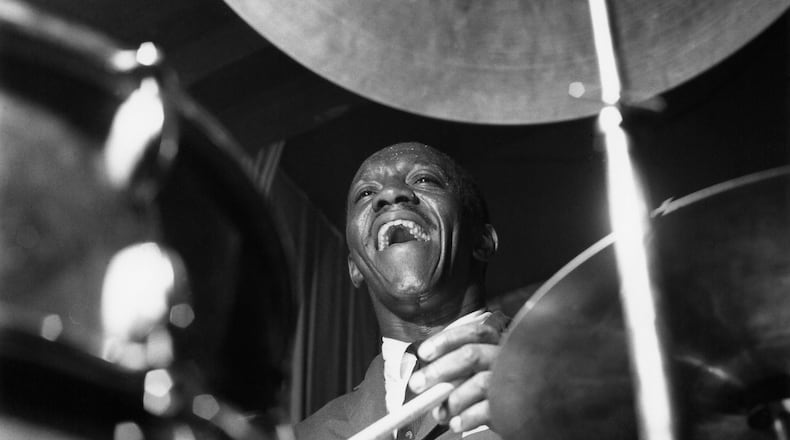

Jazz drummer Art Blakey brought a propulsive, irresistible swing to his playing, an intensity that drove his ensembles like dry leaves before the wild hurricane.

“He was a volcano,” said Gordon Vernick, coordinator of Jazz Studies at Georgia State University.

Blakey also maintained a work discipline that kept him on the road all his life, and made him give his utmost on the bandstand, whether he was feeling 100 percent or not.

Growing up in Pittsburgh during the Depression, he was orphaned as an infant when his mother died and his father ran off. Beginning at age 13, he worked full time to help support his foster family.

“I was a pianist and I worked in the steel mills and coal mines in the daytime and I played at night,” Blakey told documentary filmmaker Brett Primack. “It was just a matter of survival, cause I’m a Depression baby.”

Small and thin, but enormously strong, Blakey was tempered by the hard labor. He never stopped touring and never stopped wearing out musicians half his age.

“He was so strong,” said producer Michael Cuscuna, “if he grabbed your arm to say ‘hey, by the way,’ it was like somebody put a vice on your arm, he had so much strength in his limbs.”

That work ethic stayed with him throughout his music career.

“If I take a vacation and I’m off eight or nine days, I’m ready to climb walls,” he says, in Primack’s film. “I have to play because that’s what I love, that’s my job. When they pat me in the face with a shovel, then I quit.”

Blakey, who died at age 71, would have enjoyed his 103rd birthday this year. If he was still with us he would be able to look around and see his handiwork on all sides.

He would be celebrating former sideman Terence Blanchard’s success as the first African American composer to have his work performed by the Metropolitan Opera.

He could see another former sideman, Wynton Marsalis, presiding over the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, an institution that, for the first time, places jazz on a par with every other American art form.

He could see a musical landscape that has been shaped by the students who passed through his band, one of the great unofficial training academies for jazz excellence, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.

“I always tell people I was in the band for four years but I feel like I aged about 40,” said trumpeter Blanchard, 59, who joined the Jazz Messengers 40 years ago as the replacement for his mentor, Marsalis. “I learned so much about just being a person.”

Blanchard became Blakey’s musical director, and, like many of Blakey’s young recruits, began writing compositions and arrangements for the band. (Blakey was never known as a composer.)

“He encouraged us to write,” said Blanchard. “To develop ourselves. He would say ‘Man, you got to be working on your craft all the time.’ One of the things he also used to always say, is ‘you guys got to develop your own sound, your own period of the Messengers.’ But that’s hard, because as soon as he hit the drums, (expletive), that was the Art Blakey Messengers sound.”

Perhaps 150 musicians came through Blakey’s “Academy.” After Blakey died in 1990, saxophonist and alumni Jackie McLean said “School is closed.”

Members of the Messengers who would go on to lead their own bands and have a profound impact on jazz included Lee Morgan, Benny Golson, Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Bobby Timmons, Curtis Fuller, Cedar Walton, Keith Jarrett, Joanne Brackeen, Woody Shaw, Chuck Mangione, Wynton Marsalis, Branford Marsalis, Terence Blanchard, Donald Harrison and Mulgrew Miller.

Blakey’s early career was nurtured by the strong music scene in Pittsburgh. Switching from piano to drums, Blakey performed with other Pittsburgh natives, including pianists Mary Lou Williams and Erroll Garner.

Working in fellow Pittsburgher Billy Eckstine’s band in the mid 1940s, Blakey was exposed to the music of Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Fats Navarro and other founders of bebop, music that was new and exciting to him.

The later 1940s brought many changes to Blakey’s music and life. He traveled to Africa, converted to Islam and adopted the name Abdullah Ibn Buhaina (though he continued to perform under the name Art Blakey) and made his first Blue Note recording supporting pianist Thelonious Monk.

Blue Note co-founder Alfred Lion was entranced with Blakey’s playing, according to Cuscuna, and Blakey “became the heartbeat of Blue Note Records. He was on every session Alfred could pick the drummer for.”

(Cuscuna began his music career as a radio host and later co-founded Mosaic Records, which has carefully released exquisite box sets of historic Blue Note recordings, such as the “Complete Blue Note Recordings of Thelonious Monk,” many of them rescued from the Blue Note vaults.)

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

Lion put pianist Horace Silver and Blakey together, which led to the creation of the Jazz Messengers. Silver left the Messengers within a year, but Blakey kept the group together for the next 35 years, trading in his players for younger players on a regular basis.

“He would hire young guys, and when he felt that they were ready, if they didn’t leave on their own he would say ‘I want you to get out of here and form your own group,’” said Cuscuna. “A few people, like (pianist) Cedar Walton, he had to practically push them off a cliff to get them out.”

Blakey’s band pushed jazz in a new direction, playing a funkier, church-inspired swing that put audiences back on the dance floor. It came to be called “hard bop,” exemplified by such tunes as “Moanin’” and “Dat Dere,” both by Messengers pianist Bobby Timmons.

“To this day,” said Cuscuna, “I haven’t heard anyone that swings as hard as Art. He is joy personified. If you’re feeling low, throw on an Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers record. You’ll be fine.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured