Martin Luther King Jr. had a dream before the dream

ROCKY MOUNT, N.C. — Martin Luther King Jr. was about 12 minutes into what was supposed to be a seven-minute speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, when he was momentarily distracted by his friend and muse, Mahalia Jackson.

Standing before 250,000 people on that summer day in Washington, King said: “I say to you today, my friends…”

“Tell ‘em about the dream Martin,” the great gospel singer shouted. “Tell ‘em about the dream.”

King uncharacteristically paused.

“He sort of looked over at her,” said King’s former speechwriter Clarence B. Jones. “He took the text and moved it to the left side of the lectern. I looked at the person next to me and said, ‘These people don’t know it, but they are about to go to church.’”

King continued: “… So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.”

And with that, King launched into one of the greatest pieces of oratory in history. Americans, mesmerized by both the cadences and the content of King’s speech, didn’t know that “I Have a Dream” had been on his mind and on his lips for many months. Indeed, it may well have been born almost a year earlier in tiny Rocky Mount, N.C.

“When I first heard the March on Washington speech, it didn’t initially dawn on me that I heard it before,” said Rocky Mount resident Herbert Tillman, who in 1962 was one of more than 2,000 people who packed into his high school to hear King deliver a speech in which he repeatedly said, “I Have a Dream.”

“I started thinking about it and said, ‘You know, some of what he was saying in D.C. was some of what was said in Rocky Mount.’ But at that time, we didn’t have anything to recollect on but your own minds.”

Now he does.

‘Martin Luther King speech: please do not erase’

In August 2015, North Carolina State University scholar Jason Miller held a listening party for something many assumed had been lost forever — King’s Nov. 27, 1962, speech at Booker T. Washington High School in Rocky Mount. The speech might have been the first documented time King uttered the phrase, “I have a dream.”

“As a scholar, bringing something from the archives to the general public is a rare and exciting thing,” said Miller, who has taught English at NCSU for 10 years. “The citizens of Rocky Mount have known about this for 50 years. Now the nation and the world will know about Rocky Mount’s important moment in time.”

The search for the speech’s audio began in 2008, when Miller, a Langston Hughes scholar, started researching his book “Origins of the Dream: Hughes’ Poetry and King’s Rhetoric,” to connect the literary ties of the two.

Miller found a transcript of the speech in the state archives and visited and contacted libraries all over the country looking for the audio that produced it. Finally, in 2013, he sent a desperate email 50 miles east on Highway 64 to Rocky Mount’s Braswell Library, hoping for a lead.

The response was simple: “We have a copy.”

Traci Thompson, the local history and genealogy librarian at Braswell, said she came back from vacation in 2011 to find the reel-to-reel tape sitting in a beat-up old box on her desk.

It was marked in pencil: “Dr. Martin Luther King Speech, Nov. 27, 1962. Please do not erase.”

She doesn’t know who left it and never listened to it.

“I tried to find a place that could preserve it, but I wasn’t having a lot of luck,” Thompson said. “ Then Jason Miller came in. He flipped out.”

The reel was cracked and the end of the tape was frayed. Miller thought it might disintegrate at any moment. He drove it to Philadelphia, where a sound technician digitized and cleaned up the 55-minute recording.

Miller said he will make the audio available as an educational tool and he has not heard anything from the King Estate, which tightly controls the use of King’s image and words.

It will also be included in an upcoming documentary "Origin of the Dream," and a website www.Kingsfirstdream.com.

“I am not going to take and sell it. The only thing we are trying to do is make the audio available for the first time,” Miller said. “ This is historic stuff. This tape had just been sitting there. I wanted to be its advocate. People need to hear it.”

Calls to the King Estate were not returned.

‘To see him in person was a great joy’

The Rocky Mount that King visited in 1962 was a typically segregated Southern town in which the railroad tracks bisected the city and separated the poor and black from the white and well-to-do.

Herbert Tillman remembers the black and white water fountains and the segregated restaurants, movie theaters and schools. Whites attended eponymous Rocky Mount Senior High School.

“The serious civil rights movement was something we watched on television. Rocky Mount had a lot of relationships between blacks and whites that were long-established,” said the Rev. Tolokun Omokunde, who was 15 in 1962. “It was like, if you don’t bother me, I won’t bother you. There was no Bull Conner, but there was paternal racism.”

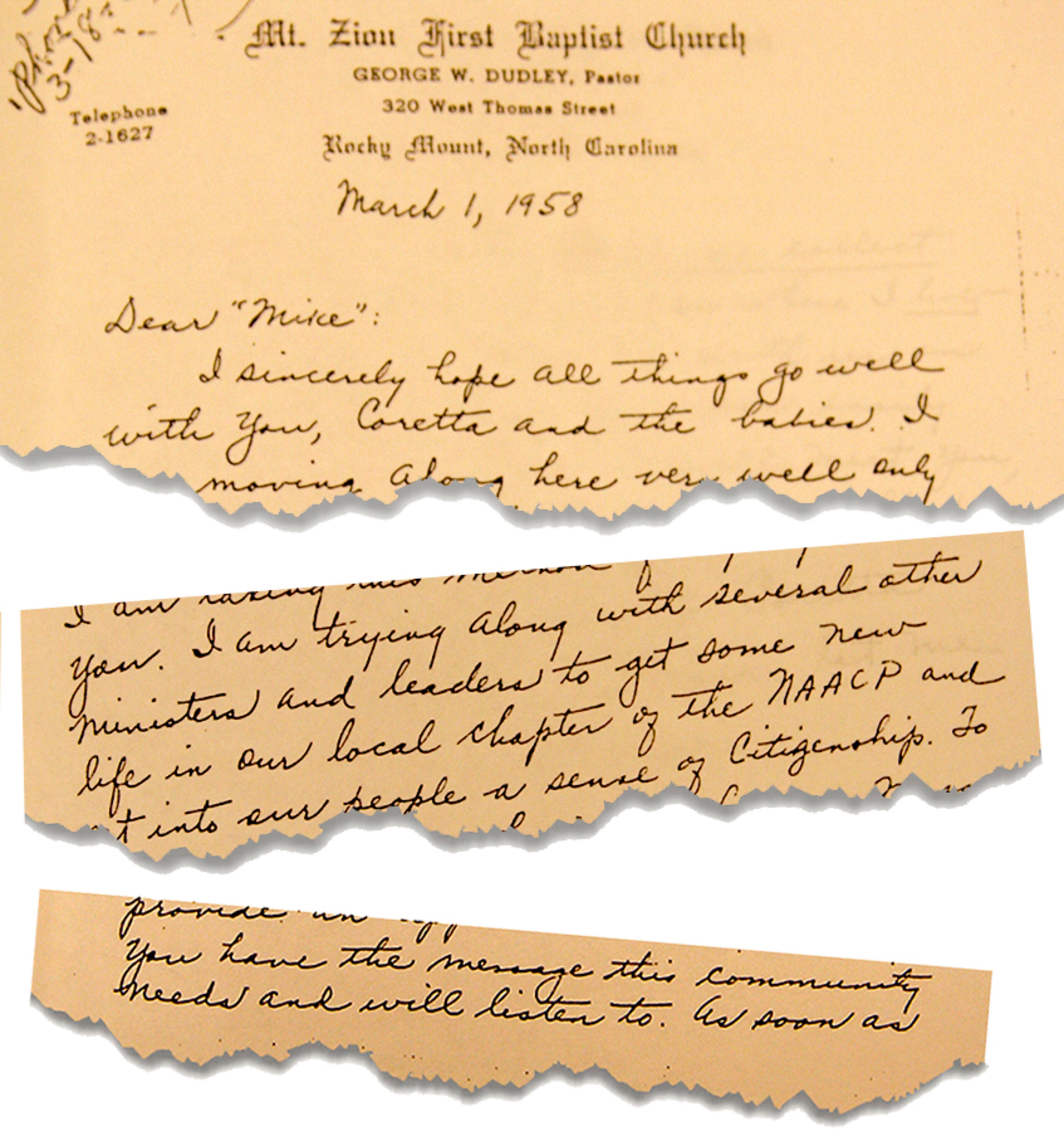

King was invited by the Rocky Mount Voters and Improvement League to help galvanize local efforts. There had been several downtown boycotts although there was never any real violence.

“To think that somebody of King’s stature would come here was a great big deal and everybody, including myself, was just so elated,” Tillman said. “To be able to see him in person was a great joy.”

Yet, when King spoke, only two newspapers – The Rocky Mount Evening Telegram and the black Carolinian – even covered it.

Neither recorded the speech.

‘The heartbeat and struggle of our people’

The links between the poems of Langston Hughes and the speeches of King have been hinted at for decades, but no one ever explored the relationship as deeply as Miller.

King started quoting Hughes as early as 1956 and the two often exchanged letters. In 1960, King wrote to the poet: “I can no longer count the number of times and places all across the nation, which I have used your poems. I can think of no better way to capture the heartbeat and struggle of our people.”

While King famously quoted Hughes’ “Mother to Son,” Spelman College English professor Akiba Sullivan Harper said, the connection goes deeper, and Hughes had been playing with the “dreams” trope for years.

In 1932, he published a collection of poems called “The Dream Keeper and Other Poems.” In 1935 in “Let America be America Again,” he wrote, “Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed.” In 1951 he published his most famous piece, “Dream Deferred,” where he pondered whether deferred dreams “dry up like a raisin in the sun?”

But the poem that most scholars point to is “I Dream a World,” where Hughes wrote: “A world I dream where black or white, Whatever race you be/ Will share the bounties of the earth And every man is free.”

“None of the images that King used were the same, but did he read “I Dream a World,” and become inspired by it? Probably,” said Harper, who edited “Langston Hughes Short Stories” in 1996. King was inspired and motivated by Langston Hughes’ use of dream imagery and metaphor.”

King openly quoted Hughes until rumors of being a communist started to dog King.

“Between April 1960 and March 1965, there was never a direct reference to Langston Hughes,” Miller said. “But you can see the ideas were still in the speeches. Hughes went to his grave believing that Dr. King’s dream was related to his own poems about dreams.”

‘Monumental event for Rocky Mount’

In 1962, the only place big enough to accommodate King in Rocky Mount was the gymnasium at Booker T.

“This was a monumental event for Rocky Mount,” Omokunde said. “This was bigger than colored day at the Rocky Mount Fair.”

Because he was a top student at Booker T. Omokunde was one of two students chosen to meet with King before the speech in 1962. Omokunde wore a brand-new blue suit, new shoes and had a crisp $5 bill in his wallet, which he said was a prop that he had to return to his parents. His hair was brushed to the side and dressed with olive oil.

“When I sat down with him, I asked him about world history, Gandhi and nonviolence. He had coffee and I had a Coke,” said Omokunde, 67, now the pastor of Timothy Darling Presbyterian Church in Oxford. “He was like an uncle or a father in that conversation. He was so guiding in the conversation that I was ready to join his movement and go forward. I left there with a swollen head, because he made me feel that I was really somebody special.”

King called his Rocky Mount speech, “Facing the Challenge of a New Age.”

“And so my friends of Rocky Mount, I have a dream tonight. It is a dream rooted deeply in the American dream,” King told the crowd. “I have a dream that one day right here in Rocky Mountain, North Carolina, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave-owners will meet at the table of brotherhood, knowing that out of one blood God made all men to dwell upon the face of the earth.”

Miller said the speech was “part civil rights address, part mass meeting and part sermon.”

“I never heard anything like it,” Miller said. “I never heard him this on-point for this long a time. In and of itself, it is quite remarkable.”

‘The earlier versions were not as good’

Clayborne Carson, director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University, said King’s language and imagery were ever-evolving.

“When you look at the earlier versions they are not as good,” Carson said. “What is happening is he is working it out in front of an audience in Rocky Mount and places in between that we don’t have recordings of. When we get to the March on Washington and he begins to speak extemporaneously, he hones it.”

On June 21, 1963, King delivered a speech in Detroit where he said: “I have a dream this afternoon that one day, right here in Detroit, Negroes will be able to buy a house or rent a house anywhere that their money will carry them and they will be able to get a job.”

There is no surviving audio, but sitting in the audience was Mahalia Jackson.

On the evening before the March, King’s advisers gave him notes on the speech, which in an early draft was titled, “Normalcy-Never Again.”

Clarence Jones wrote several pages and handed them to him, before King retired.

“I honestly didn’t know that he was going to use what I had written,” said Jones, a scholar in residence at Stanford and a visiting professor at the University of San Francisco.

‘If it didn’t happen that way, it should have’

Jones, 84, said the first seven paragraphs of the speech — including the passage about America giving the Negro a bad check, that has come back marked “insufficient funds” — were from his notes.

King’s speech was wrapped in images of the Bible, the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. There were no references to “dreams” in the typed text.

Against the din of a quarter-million people hanging on his every word, legend has it that King heard Mahalia Jackson — who had earlier sung two spirituals, “I Been ’Buked and I Been Scorned” and “How I Got Over” — call to him.

But Carson said there is no evidence that Jackson actually encouraged King at that moment on any of the audio and video recordings he has heard of the speech.

“Maybe it was a loud stage whisper,” Carson said. “It is an interesting story and if it didn’t happen that way, it should have.”

Jones, in his book “Behind the Dream,” swears he heard Jackson say it. Sen. Edward Kennedy told the same story in his autobiography.

Regardless, it was there that King cast aside his prepared text and delivered the remainder of the speech extemporaneously.

‘He could mentally cut and paste’

“I have a dream,” King said, moving from prose to poetry and borrowing from Rocky Mount. “That my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!”

“Using a current analogy, he could mentally cut and paste as he was speaking,” Jones said. “ He was going into his memory bank. People underestimate the sheer brilliance and power of this man.”

Last week in Rocky Mount, Tillman tried to visit the gym at old Booker T. — which has been converted to a community center — but it was closed for repairs. Instead, he drove about a mile up the road, where a statue of King stands at the center of a park recently named for him.

“When I heard the tape it stirred up a lot of emotions and memories in me,” Tillman said. “For Rocky Mount, I think it means that we are, as a people and city, part of Martin Luther King Jr.’s movement, whether we realize it or not. A lot of people don’t give credit to King, but Rocky Mount will always be indebted to him for coming here.”

The March 21 documentary 'The Last Days of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.' on Channel 2 kicked off a countdown of remembrance across the combined platforms of Channel 2 and its partners, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and WSB Radio.

The three Atlanta news sources will release comprehensive multi-platform content until April 9, the anniversary of King’s funeral.

On April 4, the 50th anniversary of Dr. King’s assassination, the three properties will devote extensive live coverage to the memorials in Atlanta, Memphis and around the country.

The project will present a living timeline in real time as it occurred on that day in 1968, right down to the time the fatal shot was fired that ended his life an hour later.

The project will culminate on April 9 with coverage of the special processional in Atlanta marking the path of Dr. King’s funeral, which was watched by the world.