Wyomia Tyus: Sprinter raced through racism, winning gold in 2 Olympics

At the 1964 Summer Olympics, in a race for which she was not even expected to qualify, Georgia native Wyomia Tyus emerged as the fastest woman in the world, winning gold in the 100 meters.

Throughout those Games in Tokyo — where Tyus tied Wilma Rudolph’s record during the semi-finals — all eyes had been on Tyus’ teammate and classmate Edith McGuire, a fellow Georgian whom Tyus had never beaten until the finals. McGuire finished with the silver.

Even Ed Temple, Tyus’ legendary coach on both the Tennessee State University and United States Olympic track teams, didn’t expect Tyus, at 19, to win. Temple brought her along so she could experience high-level events in preparation for the future.

Still, the coach made clear that while Tyus’ Olympic victory was unexpected, even shocking, it was not a fluke and would not be a one-time thing.

“This Tyus is not something to sneeze at,” Temple told Sports Illustrated in a 1965 article. “If I had her and Rudolph, I’d have to flip a coin. And she’s still young, just 19. Wilma was 20 when she won her three gold medals (in 1960). For Tyus, her year will be 1968.”

He was right.

From the first day of the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, Tyus supported the Olympic Project for Human Rights by wearing black running shorts instead of the team-issued white ones.

On the night of the 100-meter finals, she’d done the “Tighten Up” in front of the starting blocks while Jamaicans played bongos near the starting line. Some call that the first pre-race dancing at the Olympics. Tyus dealt with two false starts from other runners. But on the final go, she had the fastest start in her life to finish in 11.08 seconds, win the gold medal and set a world record.

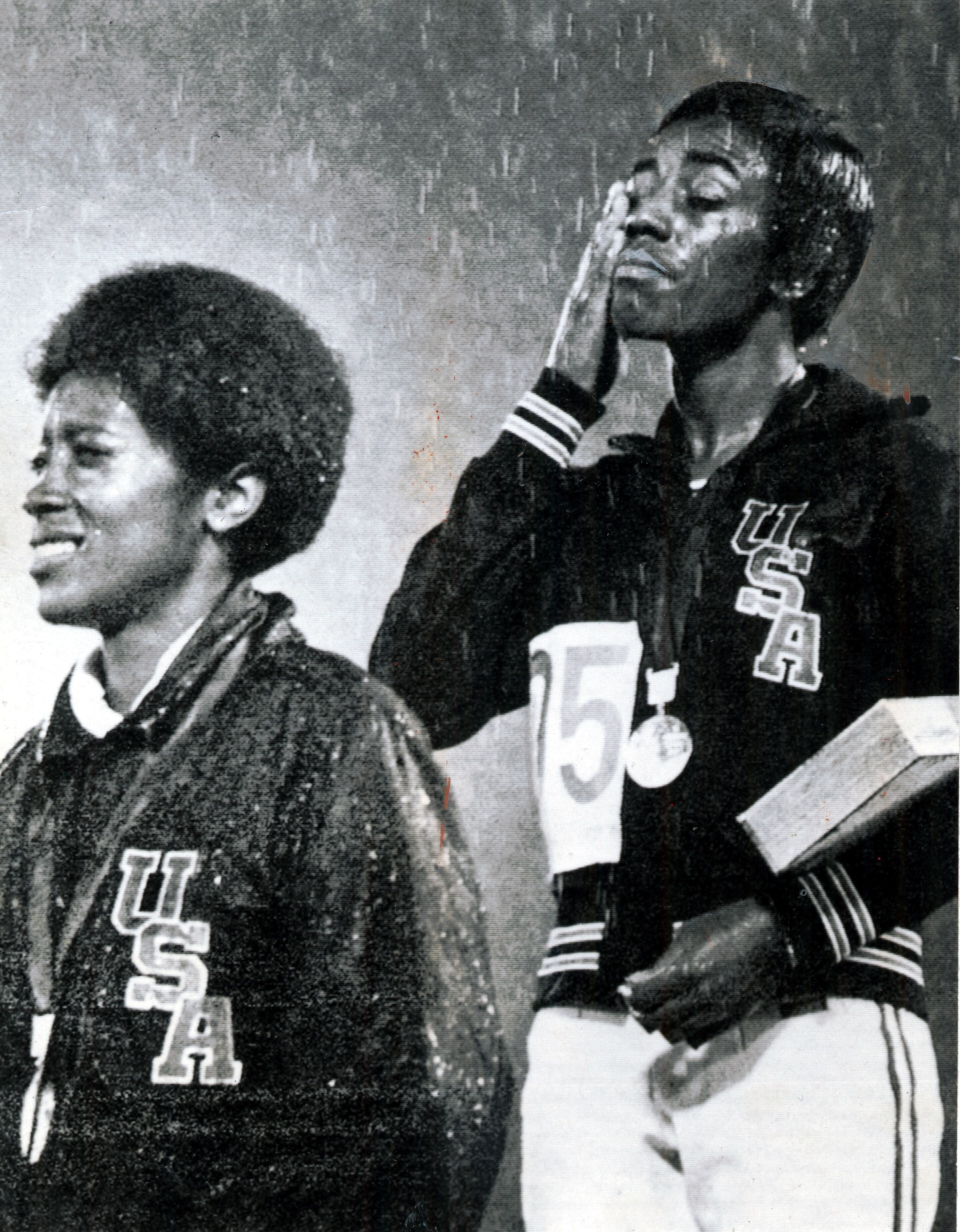

Tyus made history as she leaned forward to cross the finish line just as the rain started to pour: She’d just become the first person, male or female, to win back-to-back gold medals in the 100-meter race.

The rain continued to fall as she stood on the podium wiping the drops from her face. Tyus said many people assumed she was crying, but she was preparing for the future.

“While I was up there I was thinking, ‘Gosh, now it’s over. Now I’ve got to start a new career,’” Tyus told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in a recent interview. “And then I was all of sudden saying to myself, ‘You need to be enjoying this moment.’ After the Olympics I started to think more about it like, ‘What a great feat that is.’”

Tyus had graduated from Tennessee State a few months earlier, and at the time there weren’t many opportunities for her to continue competing, or to monetize her success.

There was also no fanfare following her historic win, other than one interview with Howard Cosell. No one brought out banners or draped Tyus in the American flag.

In her book, “Tigerbelle: The Wyomia Tyus Story,” she wrote, “At the time, they were not about to bathe a Black woman in glory. It would give us too much power, wouldn’t it?”

Plus, when people hear “1968 Olympics,” they remember something that took place after Tyus made history. Images of Tommie Smith and John Carlos usually come to mind. After winning gold and bronze in the 200-meter race, Smith and Carlos made a now-iconic protest on the podium, standing shoeless with bowed heads and raised black-gloved fists while the United States national anthem played.

The two were kicked out of the Olympic Village. And when Tyus and her team — made up of Barbara Ferrell, Margaret Bailes and Mildred Netter — won gold in the 4x100 meter relay, she dedicated her medal to Smith and Carlos.

*** *** ***

Wyomia Tyus grew up on a dairy farm in Griffin, about 40 miles south of Atlanta, with three brothers and her mother and dad. She was 14 when her father died.

By the time she was 15, she’d already taken up track and qualified for the state meet in Fort Valley. That’s where she met Ed Temple, who recruited her for a summer camp at Tennessee State and an opportunity to train like a Tigerbelle.

The Tigerbelles, the decorated Tennessee State track team, won 34 national championships in 44 years. Temple, who died in 2016, trained 40 black female Olympians who won 23 Olympic medals overall, 13 of them gold. The Tigerbelles also dominated U.S. track and field in the 1960s. This was before the passing of Title IX, the federal civil rights law that, among other things, created equal opportunities for women to participate in collegiate sports.

Tyus often quotes Temple — whom she respectfully calls Mr. Temple — and reveres him as someone who helped to make her who she is today. She repeats phrases he used, such as “track opened the doors, education would keep the door open,” and still remembers beliefs he preached, such as supporting your teammates and making friendships outside of sports.

“To see that Mr. Temple could do these things with all black women, accomplish all these things and also give these women an education, not just in college but see the world … That was so mind-blowing,” Tyus told the AJC.

The Tennessee State summer camp changed everything for Tyus.

Temple would bring 20 to 30 girls from throughout the South to the university and allow them to train, watch films and learn what it was to be a Tigerbelle.

Tyus didn’t have the words for it back then, but the Tigerbelles became her role models and expanded her worldview.

Her father always told her she could be whatever she wanted, but the Tigerbelles were living examples. When she and her camp mates watched films of eight-person races, six of the competitors would be Tigerbelles. Tyus also met a Tigerbelle who majored in math. Before then, she hadn’t known any woman who’d majored in math.

“I grew up thinking I’d become a teacher or a nurse, but when I went to Tennessee State, I realized, ‘No, you don’t have to be the nurse, you could be the doctor,” she said.

Tyus’ journey had its lows. At the 1967 Pan American Games, after suffering a leg injury, she performed horribly in the 100 meters. But she refused to go back to Tennessee without any success, so she persuaded Temple to put her in the 200 meters. She won.

RELATED: Mamie “Peanut” Johnson: Pitching pioneer

RELATED: Simone Biles: Gold medal Olympic gymnast soars to new heights

RELATED: High-flying Hawks: Maryland Eastern Shore hoops broke HBCU barriers

Tyus said playing with her brothers as a kid in Griffin fueled her competitiveness.

“I always wanted to be the person who could run the fastest, ride my bike the best, climb the tree farther than anybody else, throw the ball,” Tyus told the AJC. “And that was just everyday practice, every summer.”

Tyus also said she always had a desire to be more, but when she was growing up, women who ran were rarely encouraged to keep going.

She laughed as she recalled the things she was told. “‘Muscles are ugly on women, and no man would want a woman with muscles.’ How wrong were they? ‘You would not be able to have children.’ How wrong were they? Those kinds of things. ‘No man would want you if you’re better than they are.’ Well you don’t need to be with that person anyway, that was my way of thought.”

Tyus persevered, set records, and was inducted into state, national and international halls of fame.

“Every time they talk about the 100 meters, they have to mention my name,” Tyus wrote in her book.

In 1999, her hometown of Griffin, which displayed “Coloreds Here” and “Whites Only” signs during Tyus’ childhood, unveiled the Wyomia Tyus Olympic Park. The 164-acre park in Spalding County has soccer and baseball fields, picnic areas and a lake.

Twenty years later, the park’s existence still astounds her.

“People always tell me, ‘I was at your park, I was at your park,’” she said. “And when you read about it, ‘Tyus park,’ I’m like, gosh,” Tyus said. “It’s kind of like, my goodness, OK, I’m winning the Olympics all over again.”

BLACK HISTORY MONTH

Throughout February, we’ll spotlight a different African-American pioneer in the daily Living section Monday through Thursday and Saturday, and in the Metro section on Fridays and Sundays. Go to AJC.com/black-history-month for more subscriber exclusives on people, places and organizations that have changed the world, and to see videos on the African-American pioneer featured here each day.