Who shot the sheriff? Justice elusive for Georgia lawman gunned down 43 years ago

The call came in around midnight: a burglary at the Polk County High School.

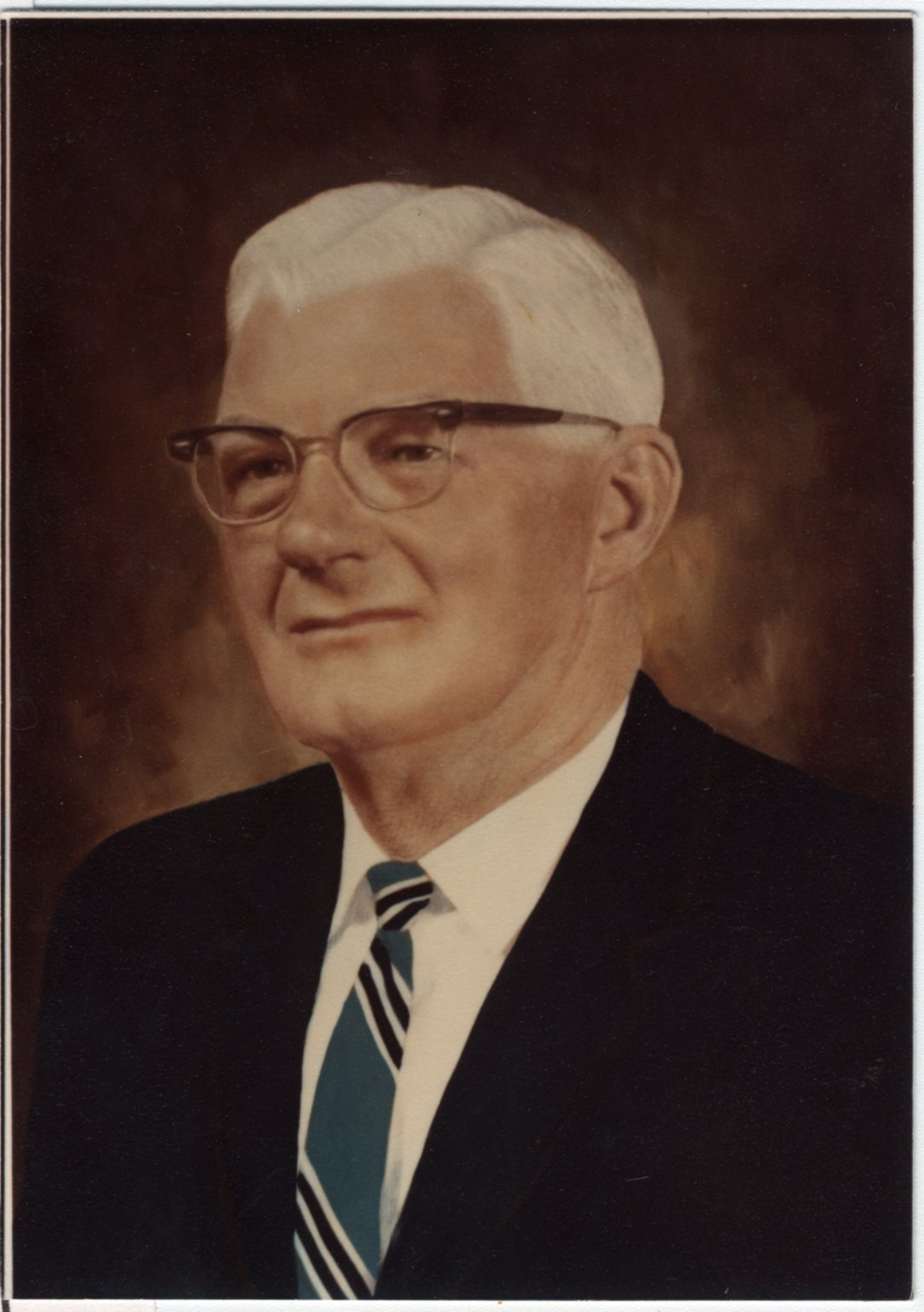

Sheriff Frank Lott, back from dinner with his family at the Bonanza Steakhouse, was minding the jail in Cedartown while the rest of his tiny force attended to a problem at nearby Hightower Falls. So, Lott enlisted Benny Clark, a 29-year-old “trusty” serving 90-days for DUI, to come along.

Near the main schoolhouse was a car that resembled the Gran Torino featured in the hit TV show “Starsky and Hutch.” Lott pulled up his patrol car nose-to-nose to block it in.

“Hey boy, what you doing up here?” the sheriff asked as he approached the headlights.

The driver answered by pulling the trigger on a .22-caliber revolver, hitting Lott three times and Clark once in the groin area.

“Take my gun and shoot him,” the wounded Lott shouted to Clark as the car sped away.

Clark radioed for help, loaded the wounded sheriff into the backseat and sped to the hospital.

“Benny, hurry up. I’m getting cold,” Lott urged.

The 66-year-old farmer-turned-lawman died soon after they arrived at the emergency room. It was June 22, 1974.

The killing rocked the small Polk County community, located in a rural stretch of northwest Georgia along the Alabama border.

Forty-three years later, no one has been convicted.

Technically, the case remains unsolved. But unlike a typical cold case — where the perpetrator remains unknown or at large — many in law enforcement believe they let Lott’s killer slip from their grasp.

Larry Harold Johnson was tried for the murder in 1999. But a jury acquitted him.

“As far as I’m concerned, it’s solved,” said Polk County deputy Mike Sullivan, who arrested Johnson for murder just months after being assigned to the case. “The guy got away with it, and he will never be tried again… I have no doubt in my mind that Johnson killed Sheriff Lott. Johnson just got lucky.”

‘People Forget’

There are several theories about why a Polk County jury voted to acquit Johnson when so many people were certain of his guilt.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reviewed court records and investigative files and interviewed those close to the case to create a picture of how the investigation progressed and the problems along the way that allowed the murder of a sheriff to go unpunished.

Too much time had passed, said Sandra Galloway, who was the court clerk at the time and was there every day for testimony at the trial.

“People forget. Evidence gets misplaced,” she said. “When you have a case like that, time, it is not good.”

But the case also became mired in turf battles as various lawmen jockeyed to solve the high-profile killing.

“Everybody … felt like if they could solve this case, they would be sheriff,” said the sheriff’s son, also named Frank. “They all went in different directions.”

Though the trial came a quarter century after Lott’s death, it emerged that Johnson had been questioned as a suspect just two years following the shooting. The examiner who administered a polygraph test to Johnson determined he either killed the sheriff or knew who did. Nonetheless, he was released.

COLD CASE: Beheading mystery confounds Georgia sheriff

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: The AJC’s crime and public safety Facebook is your source

Seals Swafford, who succeeded Lott as Polk County sheriff, didn’t share that information with the agencies running the investigation — the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, the FBI and the Polk County Police Department.

Swafford testified at the 1999 trial that he simply forgot to pass along the information.

But investigative records also show that Swafford felt left out of the probe. He complained that “not one time had anyone connected to the investigation, either with the GBI or local agencies, ever come by the sheriff’s department when they had a lead and had invited him to go with them.”

When Sullivan was given the old case file, he said it containted no record of Johnson’s polygraph taken in 1976. He only learned about it when he talked to the polygraph examiner who told him he thought Johnson “was a sociopath who had guilty knowledge of the crime.”

Sullivan thinks Swafford hurt the case when he testified about questioning and releasing Johnson as a suspect.

“Swafford was confused and scattered on the stand,” Sullivan said.

For instance, Swafford testified that he didn’t personally question Johnson. But Johnson testified that he did. And his account seemed to be backed up by a Miranda waiver in the old investigative file that Johnson signed and Swafford witnessed on Nov. 17, 1976.

There were also problems with ballistics and other physical evidence, said attorney Jimmy Berry, who defended Johnson.

A ballistics expert testified the bullet matched the revolver believed to be the murder weapon, but it had been tested so many times the grooves were worn. A palm print lifted from the door to the school had been destroyed the year before.

Juror David Hughes said the panel voted to acquit Johnson on Feb. 23, 1999, simply because “everybody thought he didn’t do it.” The evidence was lacking and the decision was “pretty easy,” Hughes said.

Swafford declined to be interviewed. Johnson, a month from his 70th birthday, lives in rural Leesburg, Ala., according to public records but he could not be reached for comment.

A history of violence

Johnson was a Vietnam veteran, honorably discharged in October 1968 after serving almost two years in the Army. He re-enlisted in 1981.

He also was a violent man, according to court records. He broke his first wife’s arm and leg. He choked his second wife unconscious and threatened to kill her after they divorced. In 1990, Johnson beat his third wife with a rifle, putting her in a coma, and she died in 2008. Johnson spent three years in prison for that attack.

Court records also show Johnson had three children with three different women. His first-born, a son, told investigators that his father abused him and his sisters.

But Johnson’s mother, Ellen, told investigators who came to search her Leesburg home that she had “brought him up to love the Lord” and if he “had in fact done something wrong it was because he had gotten into the wrong crowd.”

In between his stints in the Army and his time in prison, Johnson drifted from job to job and state to state. His only permanent home was a cabin without utilities that he built on his mother’s property.

That’s where he fled to after leaving Polk County in 1974.

For about a month, Johnson had lived with five others, including then-girlfriend Joan Miller, in Aragon, Ga. and worked a factory job in Rome.

But the day after Lott was killed, Johnson suddenly announced he had to leave Georgia. Johnson told friends he was worried that he fit the description of Lott’s killer, a man with “long, flowing blond hair.”

So, Miller’s brother drove Johnson to Interstate 20 about 30 miles away so he could hitchhike back to Leesburg.

After Johnson left, his friends in Georgia started discussing whether Johnson had killed Lott and in 1976 one of them, Bonnie Waller, reached out to then-Sheriff Swafford. She told the sheriff that Johnson had been “living like a hermit in a cabin in Alabama” but was back working in Georgia.

Swafford questioned Johnson and let him go despite the incriminating results of the lie detector test, records show.

Meanwhile, GBI investigators were floundering.

“We had suspects, but we eliminated all of them. (Johnson) never came to the GBI’s attention,” said GBI director Vernon Keenan, then a new agent sent to the Cedartown area to help with interviews.

“It was very frustrating,” said Lewis Evans, who was the primary GBI agent assigned to the investigation.

‘I hated to publish the verdict’

But in October 1997, Sullivan, the Polk County deputy, was asked to give the cold case a fresh look and soon an informant came to see him.

“I’m going to tell you who killed Sheriff Lott,” Sullivan recalled the informant saying.

Larry Harold Johnson was the name.

In following up, Sullivan had people describe Johnson as mean, strange and weird. A former girlfriend who told Swafford about Johnson repeated for Sullivan what she had told the then-sheriff two decades earlier.

Lott’s family was stunned.

“We had resigned ourselves to the fact that we would never know who did it,” said the sheriff’s son.

When Sullivan visited Johnson’s mother, he came away with key evidence — photos of Johnson taken in 1974 and a “short” 22-caliber revolver that turned out to have been the murder weapon.

The state’s ballistics expert said the gun was a 99 percent match. But the bullet taken from Lott’s body in 1974 had been worn by repeated testing so officials exhumed Lott on Feb. 12, 1999, in the hope a bullet still in his body could be tested; it could not.

Still, Clark — the trusty from the jail who had been with Lott that fateful night — easily identified Johnson from two photo line ups.

“Benny looked for him all these years, always looking over his shoulder because he was the only witness,” Sullivan said.

Johnson, then working for a fencing company is Alabama, surrendered on Feb. 21, 1998, but still asked why he was being charged. “Johnson stated that he had been cleared of the Lott murder in 1976,” according to records.

He went on trial in the summer of 1999.

“I believed he had done it. We had too much evidence,” Sullivan said.

The jury didn’t agree. On July 9, 1999, Galloway, the former court clerk, announced the verdict.

“When I looked at it, I hated to read it. I hated to publish the verdict,” she said. “I think we expected it to be resolved. But it was just over.”

Two years later in a strange coda of sorts, Benny Clark was killed by his wife. She was also represented Berry. She, like Johnson, was acquitted of shooting Benny Clark.