Where is it? Testing to learn how many have had virus begins in Ga.

State and federal public health agencies plan to screen people in parts of Fulton and DeKalb counties over the next seven days for antibodies to the novel coronavirus to pinpoint who might have had COVID-19 and estimate how widely the virus has traveled.

The Atlanta-based Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state and local health boards in both counties will visit 420 randomly selected households through May 4 seeking volunteers to give blood samples.

Until recently, diagnostic testing for the coronavirus, which detects active cases, has been limited generally to the sickest individuals, first responders and health workers and people at high-risk for COVID-19. As a result, public health officials missed key insights into the full scope of the disease and how widespread it is.

Researchers hope antibody or serologic testing will fill in those gaps, reaching back in time to detect people who had the disease in the past. Antibodies are an immune response to infection, and the presence of them suggests the person was infected with the virus whether they showed symptoms or not.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said last week that an antibody testing survey had found more than one in five New York City residents showed signs of having had the virus. If accurate, the data suggests a far broader spread than previously known as well as much lower death rates.

In the long term, many scientists hope expansion of diagnostic and antibody testing to the broader population will help guide decisions to fight the virus and reopen the economy. Further analysis of antibodies could one day lead to treatments for COVID-19, but there is much left to learn about whether or not antibodies to this virus offer protections.

Results from some antibody tests to date have been dubious. The New York Times reported Friday that researchers found only three of 14 antibody tests currently on the market produced results deemed consistently reliable.

Serologic surveys in parts of California suggested far more infections than many predicted. But those surveys also have been criticized for flaws in how researchers recruited volunteers and the demographics of those tested, which might have skewed results.

The CDC did not make anyone available for an interview before deadline. The agency is conducting other similar studies across the nation.

In a press release, the agency said blood tests are voluntarily and only the randomly chosen households will be allowed to participate. Investigative teams will do interviews and take blood samples of all household residents if they agree to take part.

“Serology testing can tell us how many people may have been infected with the virus but it can’t determine if a person has an active COVID-19 infection at the time the sample is taken,” CDC spokeswoman Kate Fowlie said in an email. “It also can’t tell us for certain if someone has immunity right now. We don’t know yet if the presence of these antibodies can protect a person against a reinfection or how long the antibodies might protect someone.”

Judging by reactions on the Georgia Department of Public Health’s Facebook page, many Fulton and DeKalb residents might be skeptical of phlebotomists and epidemiologists showing up unannounced on their doorsteps.

“There is a lot of distrust right now,” one commenter said. “I think asking people to come to you would work a little better than knocking on doors.”

Dr. Kathleen Toomey, Georgia’s commissioner of public health, urged people contacted by the CDC and state and local health officials to participate.

“This is another way that Georgians can play a role in helping fight this virus,” she said.

Uncovering missing data

Georgia tested so few people early on, the number of confirmed cases of the disease statewide — about 24,000 — is likely a significant undercount, experts say.

The hope is antibody tests will help unlock some of that missing knowledge.

“From an epidemiological perspective we’re not seeing the full picture,” Allison Chamberlain, acting director of the Emory University Center for Public Health Preparedness and Research said in a recent interview.

Through Sunday, Georgia ranked 35th nationally per capita in diagnostic testing, according to an Atlanta Journal-Constitution analysis of national testing data. Experts say Georgia and the U.S. at large need a drastic increase in testing capacity to help contain the virus and to return to something that resembles normal life.

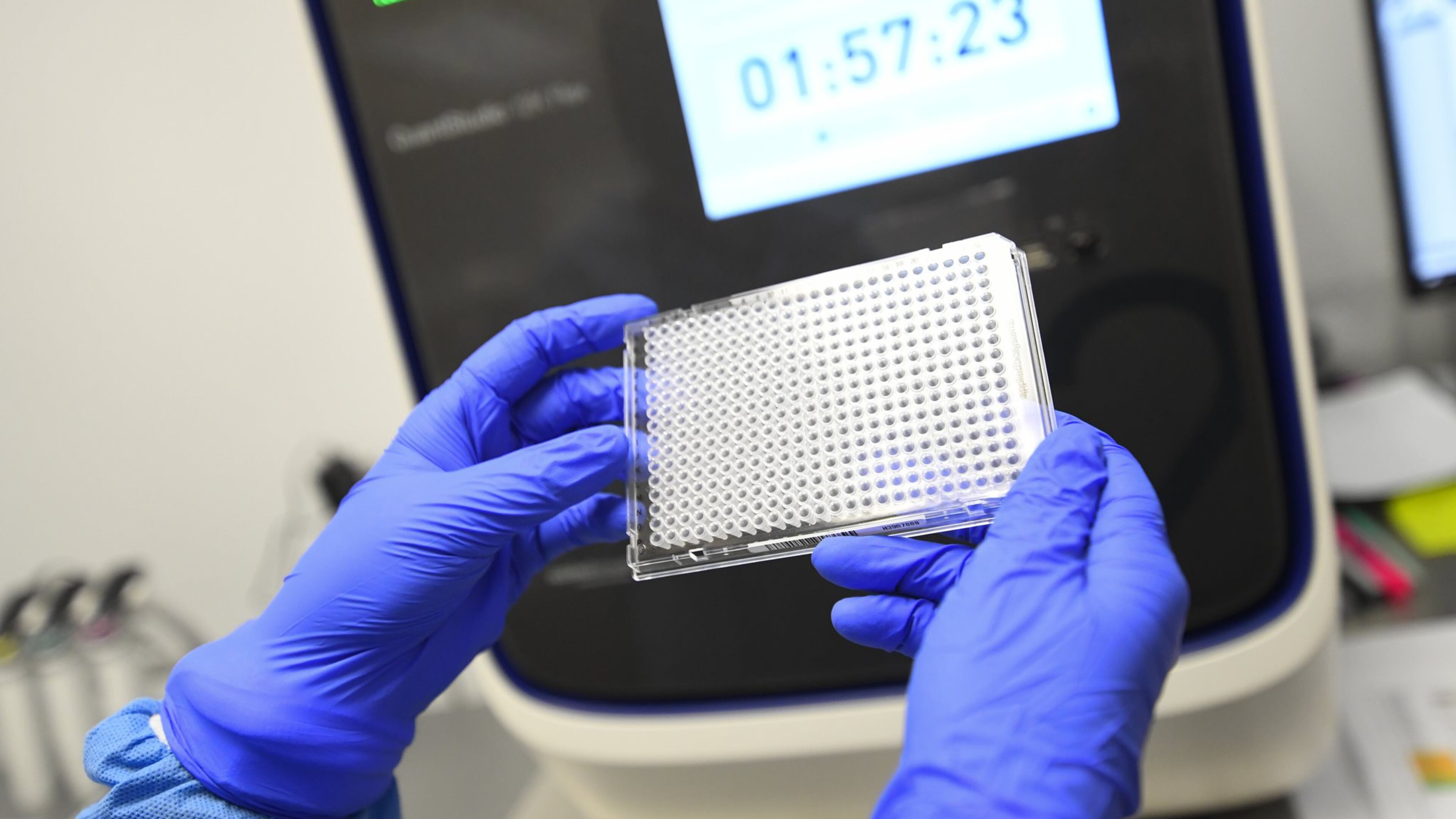

Emory scientists have developed a COVID-19 antibody test they hope to make broadly available by mid-June with capacity to test 5,000 people per day.

“The antibody test lets us know someone has been exposed to the virus in their body,” Dr. Aneesh Mehta, associate professor in the division of infectious diseases, Emory School of Medicine, said in an interview this month. “What we want to learn in the coming weeks is how well those protect someone from COVID-19 infection.”

Some countries have reported patients experiencing reinfections of the disease, according to BuzzFeed News.

Researchers also are trying to find the presence of neutralizing antibodies, a powerful immune response that prevents infection from happening. If scientist find these defenses, they might also develop a separate test to detect them, Mehta said.

They might also be able to develop therapeutic treatments against COVID-19. The goal is to pinpoint the protective antibodies and invite patients who have recovered from the disease to donate plasma to develop treatments.

In the long-term, Mehta said the antibodies might help develop better vaccines against the disease, he said.

‘The hard way’

Companies are rushing tests to market to detect antibodies.

Some nations, including Italy and the United States, are exploring if it might be possible to issue “immunity certificates,” documentation that a person is immune from COVID-19 and free to return to work, BuzzFeed News reported.

But the science for antibody testing isn’t there yet, said Drew Maloney, chairman of Capstone Healthcare, a molecular and genetics diagnostic lab in Sandy Springs.

Maloney said the rate of faulty results should be concerning.

In Europe, many countries purchased antibody tests from China that proved highly inaccurate, he said.

“The reason people focused on (antibody testing) is it seems like this answer is better than the hard answer, which is to do it the hard way,” Maloney said.

That hard way, Maloney said, is wide-scale diagnostic testing over the long term until scientists can develop a vaccine.

Antibody vs. diagnostic testing

An antibody or serologic test uses a blood sample to detect signs of immune response showing past infection. Diagnostic tests using a nasal or throat swab attempt to detect current infection. Testing at hospitals, clinics and drive-through centers in Georgia so far have generally been diagnostic tests.