Virus, lack of preparation lead to Fulton County election disaster

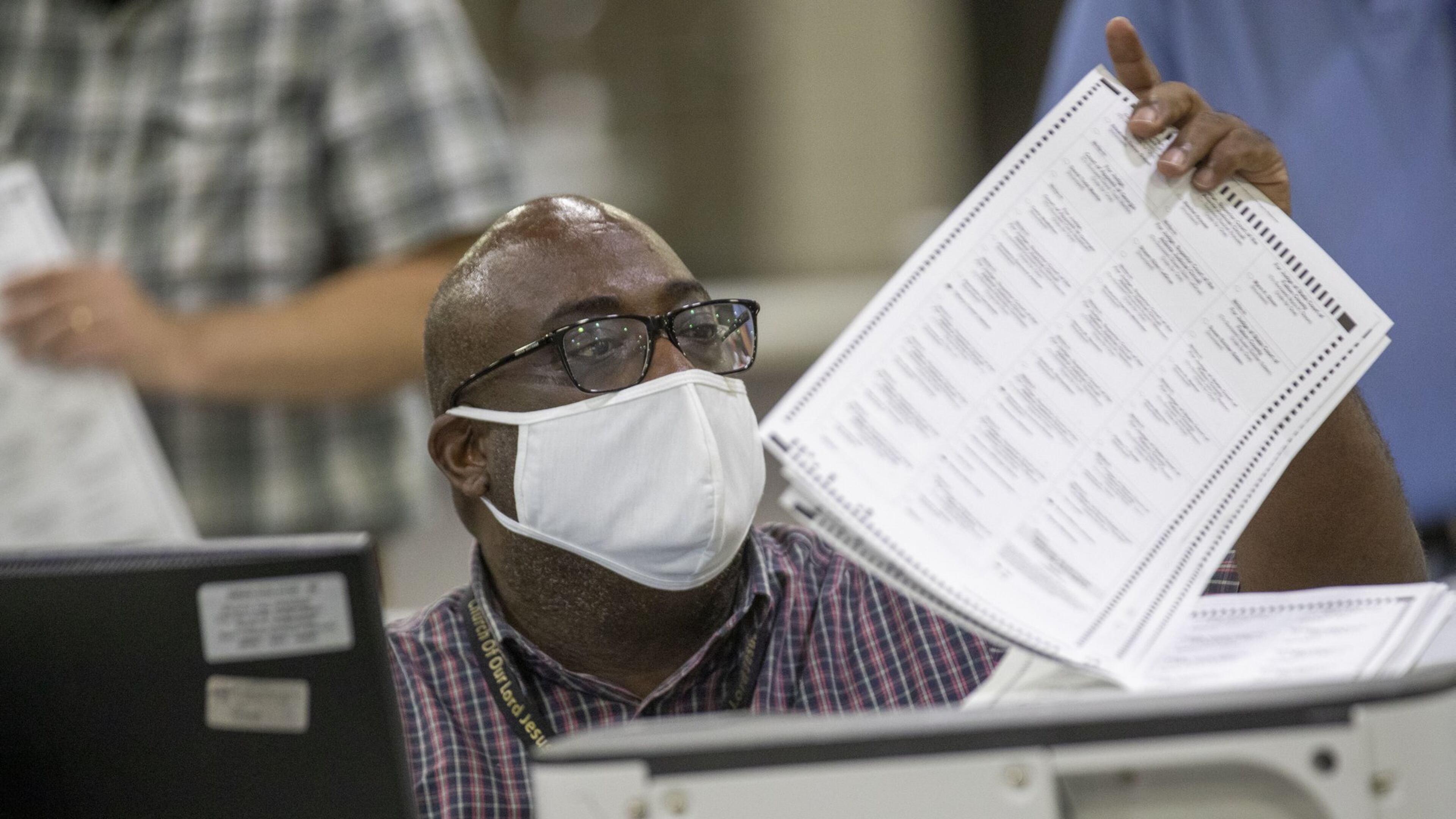

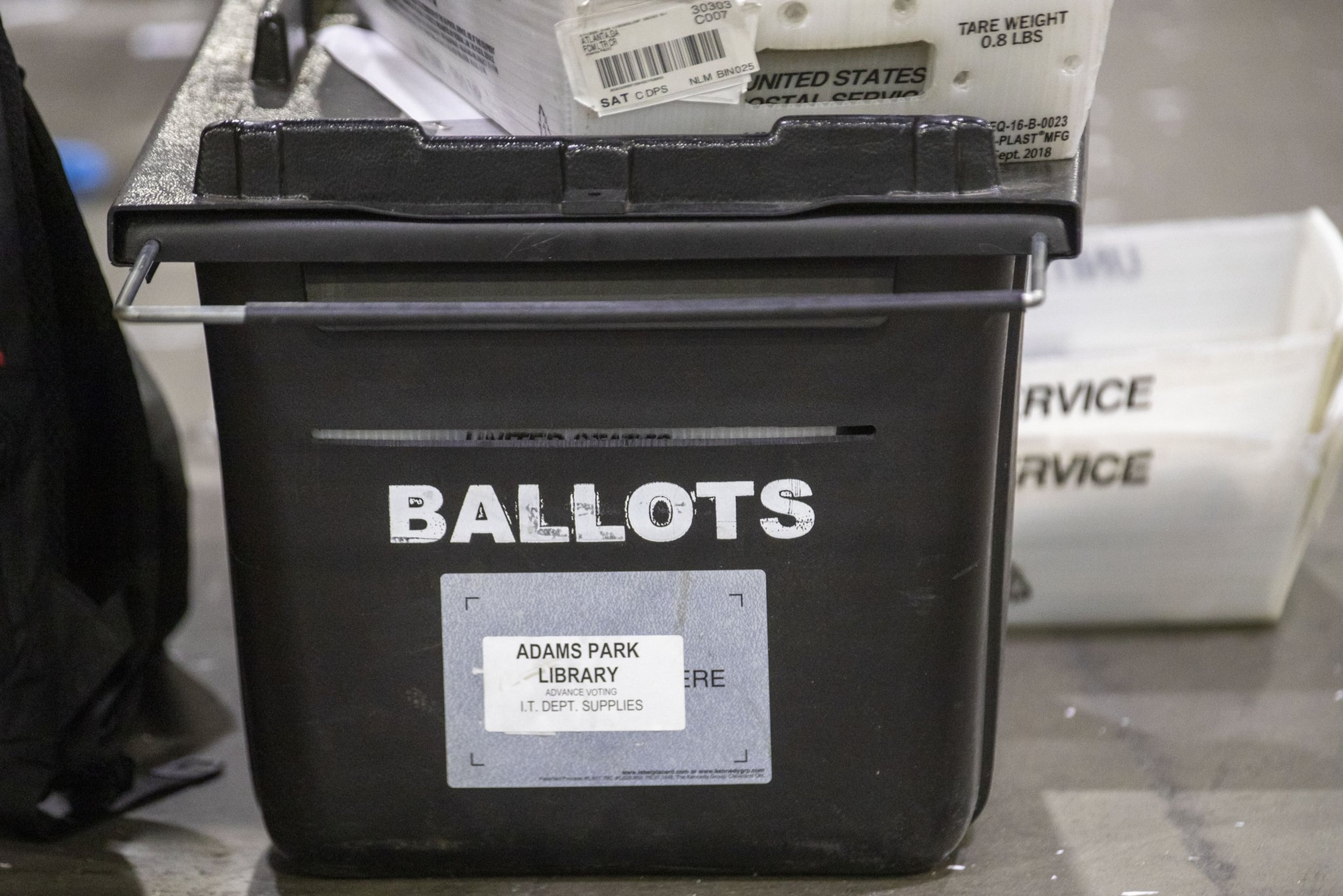

As county staff spent Wednesday deep in the Georgia World Congress Center counting mailed absentee ballots, the world took stock of another disastrous election in Fulton County.

For reasons that are both simple and complicated, bi-partisan and polarizing, voters waited hours Tuesday to cast ballots in a county known for Election Day foibles.

“I still don’t understand what all happened,” Fulton Commissioner Lee Morris said Wednesday.

Morris and many others frustrated by the county’s performance said conditions were building for a perfect storm of failure. New voting machines, unprepared precincts and a global pandemic all added to the chaos.

Final vote tallies aren’t expected until Friday.

Fulton Commission Chairman Robb Pitts announced Wednesday he is forming a task force to figure out what happened, and how to fix it before the August runoff and November general elections. Pitts said the group will be chaired by County Manager Dick Anderson and comprised of county executives, business leaders and a consulting firm.

Tuesday’s problems should have surprised no one, because they were slow-moving like a hurricane. But the magnitude did surprise even those who’d weathered storms before.

Morris, a former Atlanta city councilman who has voted in every Fulton election since 1981, said the scale of Tuesday’s problems may be unprecedented.

“This may be the worst of them,” he said.

The county commission doesn’t run the election, but it does appoint the elections board chairperson, currently Mary Carole Cooney. Her board works with Richard Barron, Fulton’s director of registration and elections, to plan and execute the election.

The board plans to discuss the week’s mishaps during an 10 a.m. virtual meeting Thursday.

The causes range from poll workers not showing up, to issues using new voting machines being used for the first time. But all of the problems were either created or worsened by two things: a backlog of absentee ballots that forced voters to the polls, and voting machines that didn’t work properly because of staff errors or late deliveries.

MORE | Voting machines and coronavirus force long lines on Georgia voters

That was the assessment of Fulton Commissioner Bob Ellis, who said his first inkling of trouble Tuesday came at 7:15 a.m., when a friend messaged him about problems at a Milton precinct. Ellis saw dozens more complaints when he logged on to social media.

“There are both Democrats and Republicans who are not happy with the way anything went down yesterday,” said Ellis, who like Morris is a Republican.

Problems around the state caused judges to keep the polls open longer Tuesday, but Fulton was the epicenter.

“If there’s going to be a problem anywhere in the system, it’s going to show up in your largest county,” Ellis said.

READ | Georgia's election problems blasted as November vote looms

The problems came quick in Fulton, mostly because many poll workers had never had their hands on the equipment before.

Georgia awarded Dominion Voting Systems a $104 million contract last summer to provide more than 75,000 new computers and printers. The 18-year-old electronic machines in Fulton lacked a paper ballot and were being replaced with a patchwork of touchscreens, printed ballots and scanners.

Ellis said the elections staff could have expected issues, considering in-person poll workers training ended in March due to COVID-19. He said the lines grew Tuesday as poll workers had trouble getting technical help from the county when things went wrong.

“This is mismanagement on Fulton County elections’ part,” Ellis said. “This particular elections board has got to look critically at the leadership and management within the elections department.”

MORE | New voting machines lead to lines and problems on Georgia election day

Barron told reporters late Tuesday night that he and the board of elections plans to bring in a consultant to analyze what went wrong, especially with their system to distribute absentee ballots.

An unknown number of emailed absentee ballot applications got stuck in a county server, leaving many voters confused and forced to vote in person amid the pandemic. That’s exactly what Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger was trying to avoid when he mailed absentee ballot request forms to the state’s roughly 6.9 million voters.

The county couldn't process applications, Barron said, because of lost time when one staff member died from COVID-19 and the leader of registrations missed work for weeks after contracting the virus.

The office had to be sanitized and people had to mourn, he said.

The day of that death, the county received the majority of their mailed-in applications. Then servers jammed. In the rush, Barron said applications that were printed might have been left at a printer or somehow not processed.

In the weeks leading up to Tuesday, Barron assured the public that all applications would be processed and people would get their ballots in time. But that didn’t happen for many people.

Then Barron said they were going to review emails to make sure no applications were missed, but many were. So voters got in line at the polls — which were fewer in number after 44 locations pulled out over fears of COVID-19, forcing the county to combine precincts.

Barron said the county also lost about 300 poll workers, who feared the virus.

DIG IN | Expanded AJC election results

Many voters stuck in massive lines on Friday, the last day of early voting, said they were there because they hadn’t received their absentee ballot. The county also opened fewer early voting precincts, assuming more people would mail in their votes. Barron said they’ll open as many early voting sites as they need to next time.

Then over the weekend, there was a rush to hire 250 poll workers, incentivizing people with a sweetened $255 a day. They were trained via video and some couldn't set up polling places the night before.

Some voters decried the problems as intentional voter suppression, former Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton among them. Clinton on Wednesday tweeted: "What happened in Georgia yesterday was by design. Voter suppression is a threat to our democracy."

State Sen. Jen Jordan, D-Atlanta, agreed. “In some ways that’s correct. If the secretary of state views their role in the minimalist way, and they know there are these same issues year after year, it effects, let’s be frank, large Democratic counties,” she said.

Because the failure was so publicized, Jordan worries progress is now less likely: “What I’m concerned about is that this is going to be politicized and it’s going to devolve into just partisanship, and then nothing’s going to get done and we’re going to be right back where we were yesterday.”