Torpy at Large: Historic building to be Wasted Away in Margaritaville

Sure, new plans in downtown Atlanta for a Parrothead Paradise topped with 200-some “vacation ownership units” might sound a bit tacky and touristy. But our city center can use all the development, foot traffic and eateries it can muster.

Hello, Wyndham Destinations and Margaritaville Vacation Club, a concept that is the result of Jimmy Buffett’s fans growing up and amassing some money. It would be 21 stories of tie-dyed luxury across from Centennial Olympic Park, within sight of the CNN Center and in the shadow of the monstrous Ferris wheel.

The project was born out of high-level negotiations between developers and the last mayoral administration. It would inject a $100 million-plus attraction into the local economy.

Not bad for an area filled with parking lots.

The only downside would be the project would bulldoze a couple of 100-year-old buildings, including one where the first country music hit was said to have been recorded. The connection would be apropos because Buffett started out as a country music crooner and then moved on to the lucrative niche of boozy beach ballads.

Like they say in development, to make an omelet, you’ve gotta crack some old buildings. I mean eggs.

Case in point is the narrow brick building at 152 Nassau Street, where in June 1923, Ralph Peer, an enterprising pioneer in a music recording industry, traveled from New York to record some local talent.

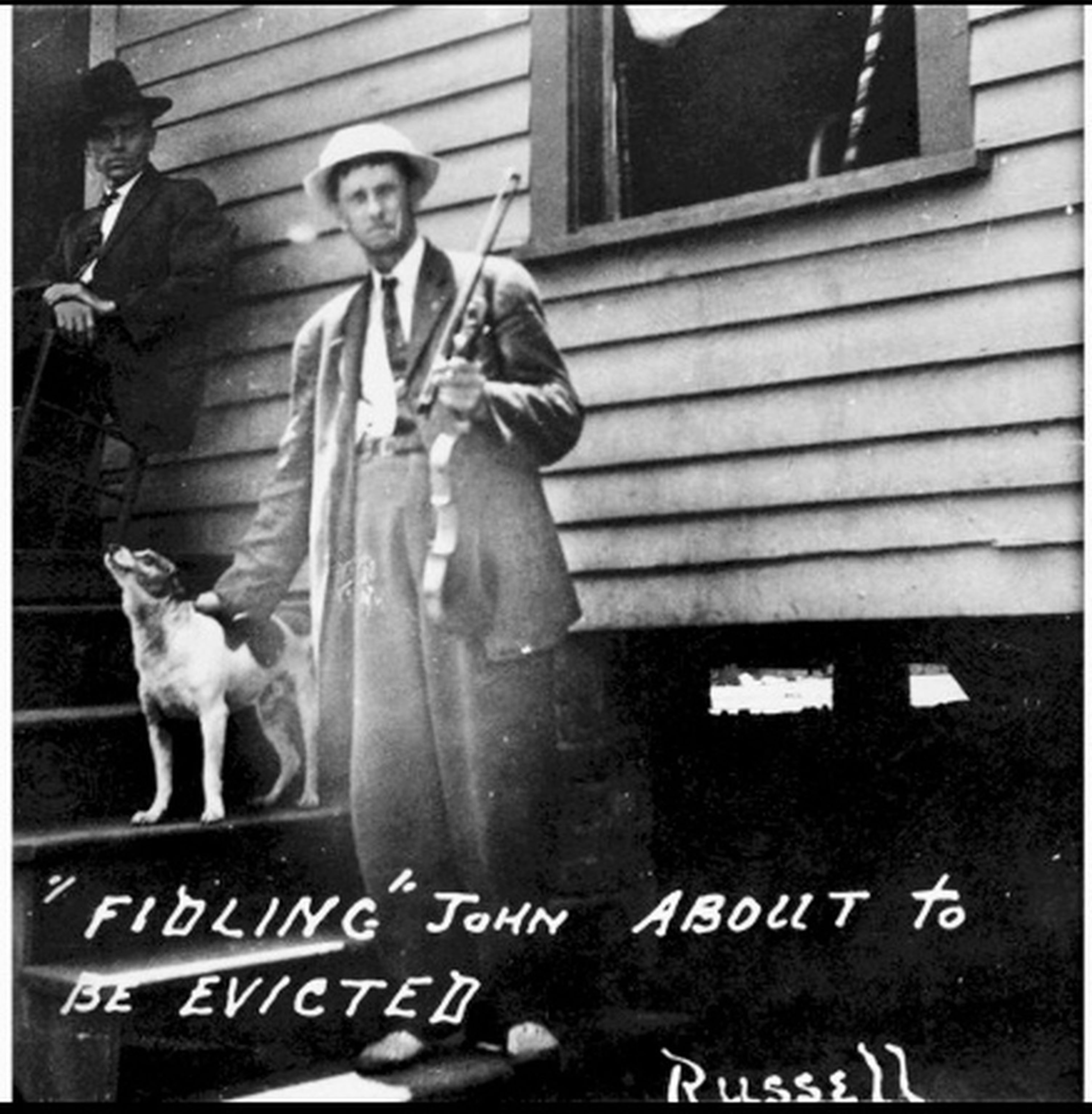

Here, he came across a cotton mill worker and moonshiner named Fiddlin’ John Carson, and music history was made.

“Peer’s first hit recording of Southern music was fiddler John Carson from Atlanta, Georgia, whose first recording of ‘The Little Old Log Cabin’ and ‘The Old Hen Cackled’ sold more than 500,000 copies nationwide,” according to the PBS program “American Experience.”

And from that, the "hillbilly" genre of recorded music was off and running, ultimately leading to Garth Brooks and Kenny Chesney sporting oversized cowboy hats and filling up stadiums. Peer, who also recorded black musicians, took credit for the terms hillbilly and "race music," according to the Country Music Hall of Fame's website. Peer belongs to that hall.

The exact site of those long-ago recording sessions on Nassau Street were hazy until a couple of years ago, when Kyle Kessler, an architect, downtown resident and preservationist, started digging into the matter.

Nassau is a short street with just a few buildings, so Kessler wondered whether the structure where the recordings took place still stood. In 2017, he came across a news clipping from the Atlanta Independent, a long-defunct black newspaper, that had the address.

At the time, developers had proposed building a Margaritaville restaurant, along with a large amusement park attraction to couple with the Ferris wheel.

Almost immediately, City Planning czar Tim Keane announced that Atlanta would designate 152 Nassau Street and a building behind it as historic, making it difficult for the developers to bulldoze them.

The developers threatened to sue. In July 2017, Lemuel Ward, an attorney for the developers, told city planners that the landmark-status process couldn’t start because his clients had already started mixing their Margarita.

According to AP, he called it a "basic issue of playground fairness." That's like not calling dibs on the teeter-totter when some other kid's butt is already occupying the seat.

The issue came to the notice of Mayor Kasim Reed, whose office helped ink an agreement to hold off on calling for the historic designation of those buildings if the developers build a top-flight hotel at least 10 stories tall and worth $100 million. The agreement called it the “golden ticket.”

Last year, the developers proposed adding 20 stories atop the Margaritaville, with a rooftop pool and all sorts of amenities that would make even the most well-heeled Parrothead squawk with delight.

However, the plan calls for a driveway on the backside of the structure between Nassau and Walton streets and knocking down the historic 20-by-100 foot building at 152 Nassau for a vital reason: You’ve got to put your garbage dumpsters somewhere.

I called J. Patrick Lowe, a senior partner with Strand Capital Group, a North Myrtle Beach firm overseeing the development. He said the effort is still on. “The brands we’re bringing in are not yet finalized,” he said.

Lowe said 152 Nassau Street is standing in the way of progress.

“I don’t think it can be configured around that and still go forward,” he said. “We couldn’t put together a parcel without that parcel.”

I asked about Fiddlin’ John and the other artists who recorded on the site where Margaritaville’s trash would go.

“We want to do the right thing to honor the history that may have happened there,” Lowe said.

Can you say plaque by the dumpsters?

Kessler, the guy who started the effort to save the building, noted there’s a vein of absurdity pumping through this saga.

"Margaritaville is a song about a fictional place," Kessler said. "What can help root that is a building with history. If I was choosing to place a music-themed attraction, placing it next to real music history would be of incredible value."

Keane, the planning chief, wasn’t part of the city’s negotiation with the developer to create the compromise. He likes the 21 stories of development but wishes the builders could keep one or both of the historic structures.

Because of the agreement inked by the city in 2017, “there’s nothing to stop them” if they follow the city’s rules, he said.

But, Keane added, “you can save old buildings and still build a development around it. Happens all the time. That’s just not the way they see the world.”

What would Jimmy Buffet do?