Torpy at Large: Cyclists, e-scooter users refuse to be a fifth wheel

You often hear about the “one percenters,” the well-to-do who alternately draw surges of envy, admiration and anger from the rest of us 99 percenters.

Today, I’m going to talk about another 1% — those in Atlanta who commute to work via bike.

Actually, it's 1.2% in Atlanta, according to a 2017 report by the League of American Bicyclists. Now, you'd think that number was much greater because they've occupied a pretty good soapbox the past few years and have slowly made inroads to getting bike lanes and infrastructure built for their safe passage.

On Wednesday, they were out in force for a rush-hour protest in Midtown, blocking off a lane of West Peachtree Road north of 15th Street as confused motorists crept through the busy intersection, wondering whether a race or a bike-a-thon was going on.

About 60 protesters and their bicycles formed a “human protected” bike lane that blocked the curb lane from traffic. They called for more protected “LIT lanes” (Light Individual Transport) because the term “bike lanes” is so 2017 with the advent of escooters and motorized skateboards and such. (I can’t say LIT lanes with a straight face, so I’ll stay with bike lane.)

The event was a spinoff from a morning rush-hour event in April, when about 100 bicyclists did a "slow roll" down DeKalb Avenue to protest the city of Atlanta deciding against bike lanes along that arterial street. (Note to those protesters: There is little goodwill to be gained by a bunch of white guys on bikes making people late for work.)

The protesters this time — a more diverse bunch — picked 15th and West Peachtree because a week earlier, William Alexander, a 37-year-old man riding a scooter, was crushed to death after falling beneath the rear tire of a bus. On Thursday, police said there would be no charges. It was Atlanta’s second scooter death.

Wednesday's protest was mostly bicycle folks trying to bring the scooterites under their umbrella. But there really is no scooter "community." Rather, it's just a bunch of random smartphone-toting folks who jump on the contraptions and ride. The city says 12,700 scooters have been permitted, with about 5,500 on the streets.

Niklas Vollmer, an organizer of Wednesday's event, said the lack of protected bike lanes may have contributed to the recent fatal accident. West Peachtree is on the list of ReNew Atlanta and TSPLOST projects and is supposed to be eventually retooled to allow for bike lanes and other improvements.

Vollmer said the city and the state “are culpable for not funding that” road improvement.

“We feel there was a victim on the scooter and a victim driving the bus,” Vollmer told me. “Other cities are building infrastructure (for bikes and such) and we’re not doing that.”

Vollmer and another organizer of the event, Andreas Wolfe, talked about how the city has fallen down on its promise to build “complete streets,” which have wider sidewalks, narrow car lanes, bike lanes and better lighting. The city has at least 15 such projects on its wish list.

Asked by a TV reporter for examples of “complete streets,” Wolfe pointed to Lynhurst Drive in southwest Atlanta.

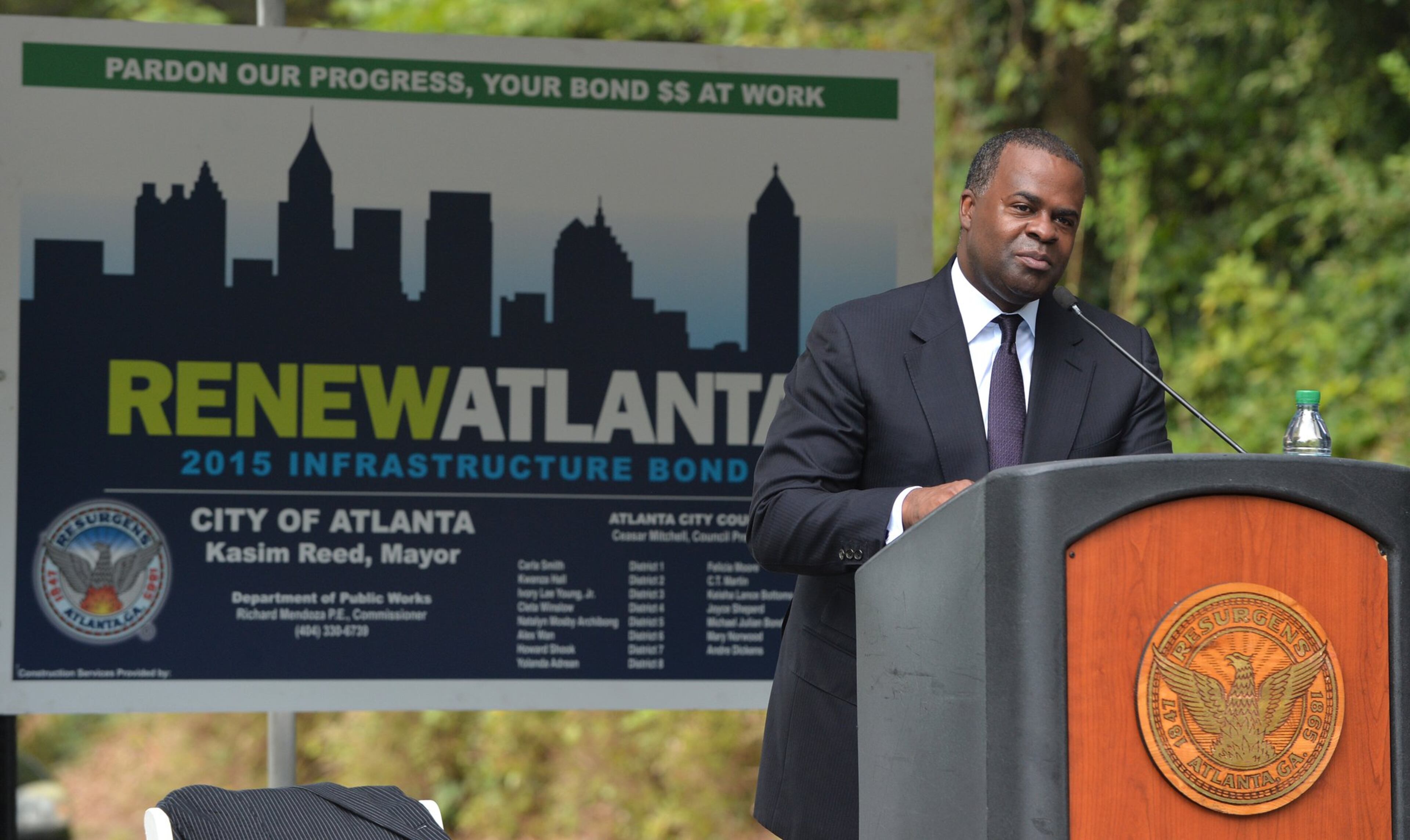

However, Lynhurst may not have been the best example. That “complete street” was the among the first Renew Atlanta projects completed and was unveiled by former Mayor Kasim Reed, just in time for the 2017 election of his favorite candidate — current Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms. Both live not far from that project.

The 2.2-mile renovation cost $6.3 million for new sidewalks on both sides, fancy brick pavers and some 300 ornate pedestrian lights that are so bright some residents jokingly say "it's lit up like the circus."

Complete streets may be great, but they are expensive. And that’s part of the problem, because Atlanta has lots of infrastructure needs — more than a $1 billion list and growing, but less than half of that in funding.

In 2015, Atlanta created a $250 million Renew Atlanta fund. And in 2016, voters passed a sales tax to raise perhaps $300 million over five years ending in 2022. But much of that has already been spent, and an audit noted considerable “soft costs,” as opposed to, ahem, “concrete costs.”

Last spring, a mayoral spokesman said $51.4 million had been spent on design and salaries and $115 million had gone into actual construction. He added that “startup costs” are more prevalent at the start of a project.

Vollmer pointed out, as did others, that the fancy pedestrian bridge built near Mercedes Benz park is now up to a cost of $33 million, according to a report in ThreadATL. Much of that funding came through Renew Atlanta money. Imagine all the complete streets and paving and pedestrian-friendly walkways that could have been paid for with that cash.

The shortage of funding has caused the city to “rebaseline” projects, meaning do fewer of them. This has neighborhoods and interest groups across the city hollering for their “fair share,” and has City Council members struggling to determine what to fund where.

At the protest, Josh Mendez rode in the impromptu bike lane on the unicycle he uses to commute from Midtown to his job at Emory University.

I mentioned that bike commuters are just a tiny segment of the population. (“Light individual transport” buffs say the 1.2 percent rate for bike commuters is misleading because some part-time bike commuters are not counted. And people take all sorts of short trips on bikes. And there’s that new batch of scooter riders.)

Mendez said there’s a sense “that if you build it, they will come. If you give people options, they will take it.”

Although drivers are often hostile to bicyclists, he said motorists usually give his unicycle a wide berth because there’s a sense, in their minds, that he’s wobbly.

So, I asked, why the beef from drivers?

“People see bicyclists as not-full adults, someone holding us all up in traffic and keeping us from our real destinations and real jobs,” said the unicyclist who’s also a physicist.