Torpy at Large: Assembling ATL’s long-delayed south downtown dream

The future of downtown Atlanta is at the intersection of Mitchell and Broad streets. Or it will be if German money has any say.

It doesn’t look like much right now. Currently, the corner consists of a barber supply store, an incense shop and a vacant lot next to a candle distributor.

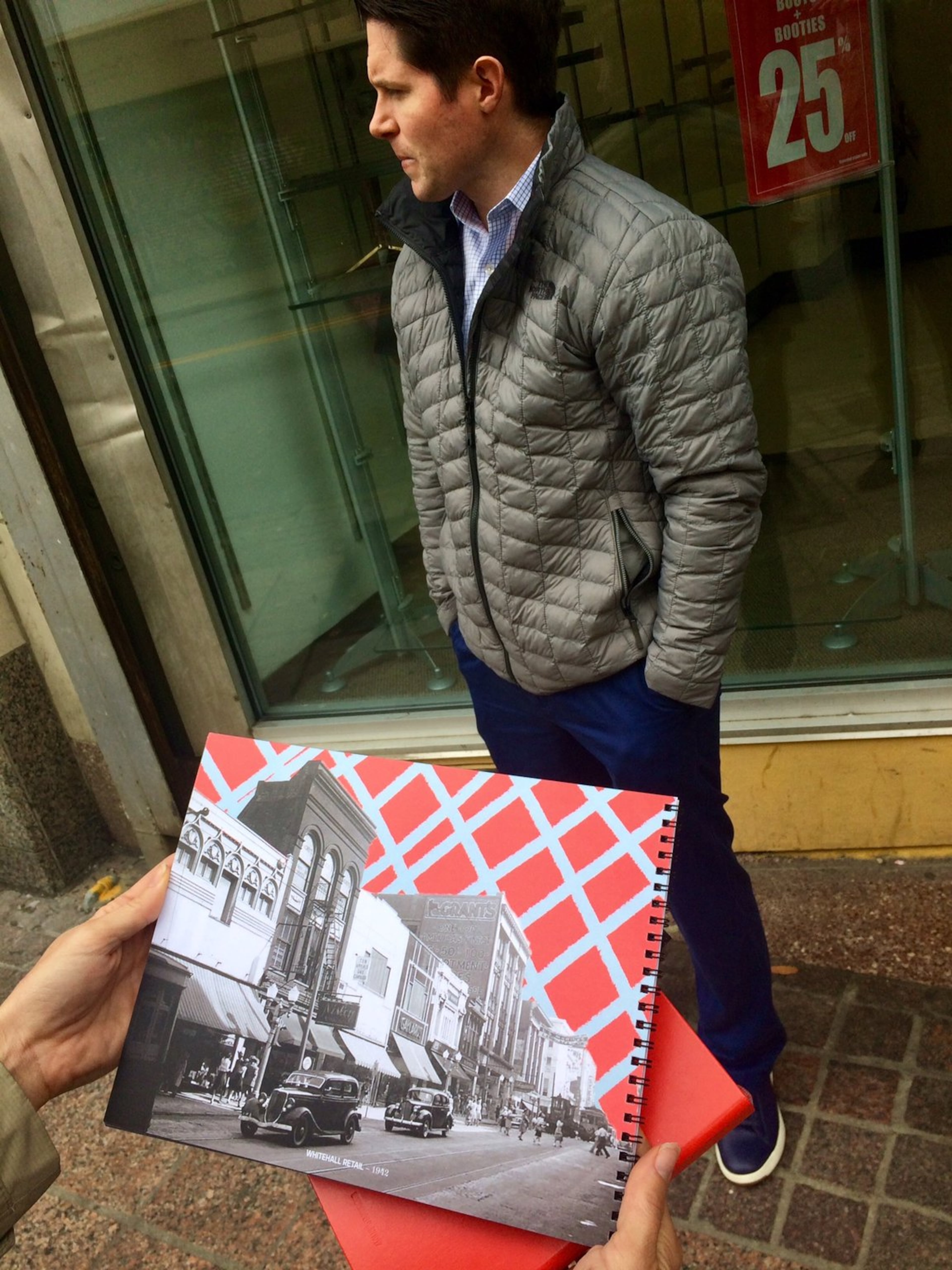

In July 2016, a baby-faced development exec walked a couple of investors from Hamburg to the corner and let it all sink in. … The possibilities. The promise.

Looking west down Mitchell street they saw the $1.6 billion Mercedes Benz stadium going up. To the east there was City Hall. And looking north up Broad street toward MARTA’s Five Points Station, they could see a festively (some might say garishly) painted collection of old buildings in need of some TLC.

"They couldn't believe why there was something like this here," said the exec, Jake Nawrocki, president of Newport US. "All these ingredients are here."

What puzzled the visitors was that here you are in the historic heart of a major city that likes to call itself world class and you’re surrounded by incense and candle shops and vociferous street people.

They wondered how all these century-old buildings survived intact. (I’ll answer that one: Atlanta developers never got around to knocking them down. The land wasn’t worth enough to bother.)

After canvassing about nine square blocks of south downtown, the visitors asked, “How many of these buildings can we buy?”

“Probably all of them,” responded Nawrocki, who used to work for the firm that turned the massive old Sears distribution center into Ponce City Market.

He wasn't off by much. Out of about 60 buildings in an area bounded by Alabama Street on the north, Pryor on the east, Trinity on the south and Spring Street (Ted Turner Drive) on the west, the investors gobbled up 47, as well as 4 acres of parking spaces. They spent about $90 million.

They knocked on doors, looked through tax records, asked shopkeepers for the names of building owners.

Often, the street-level retail was being utilized but the floors above were forgotten and boarded up. Sometimes they climbed ladders into upper floors to inspect the premises. While entering a Peachtree Street building, 15 members of their team climbed up and a guy stayed behind to guard the ladder. “We wanted to make sure it was still there when we came out,” Nawrocki said.

In all, there were 27 different owners, mostly long-timers who over the years had heard all sorts of schemes and dreams for south downtown.

Big plans for this area are by no means new. In 1984, Singapore developers wanted to spend a billion dollars to resurrect the area. Then-Mayor Andrew Young urged the area’s landowners not to get greedy and hold out for a financial killing. The Asian money men wanted 85 percent of the owners to sell at a “fair market price” for the deal to work. Young urged advocates to “pray hard” that it happened.

The prayers went unanswered.

A decade later, with the 1996 Summer Olympics looming in Atlanta, Mayor Maynard Jackson returned from the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona “absolutely bubbling about the need for downtown housing to be constructed in the empty floors above the south downtown retail spaces,” according to a 1992 AJC story.

“Every building I could see (in Barcelona) had commercial (space) in it and then five or six stories of residential (space) above it,” Jackson said at the time.

Sometimes it takes outsiders to see the value that locals can't. Maybe that's why South Carolinians are remaking the long-forlorn Underground. And California cash could redo the Gulch by Mercedes Stadium. Or perhaps that will happen with Seattle money, as in Amazon. Or maybe they don't know better.

Nawrocki, a product of Atlanta’s suburbs, said Europeans hadn’t surrendered their city centers to neglect as Americans had. They always saw value in downtowns and are happy to invest now that Americans again see them as a good bet.

The Newport folks have all sorts of grand plans for south downtown. They have released renderings with streets that are alive with cafés, shoppers, bicyclists and, perhaps most optimistic, a fashionable mom pushing a baby stroller. Nowhere is there a hint of a smelly man wrapped in a blanket muttering to himself as he wanders down the street.

The plan is not to force an unnatural development into the area. Organic growth, helped along by a majority owner looking at the long view, is the plan. A coffeehouse here, a bar there, some all-important residential dwellings, a few stores and, voila! You have momentum. They say they’ll grease that energy with $150 million more in funding.

Kyle Kessler, an architect who has lived in a condo in the area for 11 years, says the developers are employing a wise strategy.

“They’re not coming at it with preconceived notions; they can test various concepts,” he said. “It’s not like one 30-story, one-concept building. All their eggs are not in one basket.”

Two years ago, I wrote about this area after a condo resident got punched trying to scare off some crack dealers who congregate on Broad Street. The resident the other day said the dealers are still there blithely plying their trade.

A walk through the area finds numerous panhandlers and the occasional smell of weed.

Chris Yonkers, who founded the Mammal Gallery on Broad Street, said upon first moving there, “It was the most drug deals I’ve seen in blatant, open sight.”

However, he liked the deal he was able to cut in the rundown two-story building and has been able to carve out a cool music venue/arts space. He said he initially worried about the new owners but has worked out a deal to stay there for at least a few years.

Nawrocki said the artists “keep our area urban and edgy.” Street cred, grit without the threatening aspects.

Yonkers, himself raised in the ‘burbs, said Newport is “trying to do it in a light-handed organic approach,” adding, “To whitewash it and give it the Atlantic Station treatment would be terrible.”

But grit, art and coffeehouses don’t carry a deal. Creating the right vibe, getting the right mix of life and folks to live there will.

Perhaps Andy Young’s prayers will one day be answered.