Torpy at Large: Another ‘chance of a lifetime’ awaits South Downtown

Morris Habif seems to be a visionary when it comes to Atlanta real estate. Or maybe it’s just that if you hang around long enough, you’ll look smart.

In 1968 — half a century ago, mind you — The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Constitution, the AJC’s predecessors, both ran an article about Habif headlined, “Downtown Gets a Private Renewal.”

Habif, then a 41-year-old transmissions parts wholesaler, was buying up what the news story described as “old, vacant buildings which blight the downtown fringe of the Southeast’s most dynamic urban community.”

At the time, many buildings in the section of Atlanta known as South Downtown had gone vacant because garment wholesalers and other businesses had fled their aging and cramped quarters for the modernity of ample space west of the city along Fulton Industrial Boulevard.

Rather than betting on the booming ‘burbs, Habif said he was “very enthusiastic about the future prospects of downtown.” His was a lonely opinion in a city also being hollowed out by white flight.

I came across Habif while writing about the rash of out-of-town entities looking to revitalize South Downtown, which has languished for decades despite several false starts.

Currently, a California firm wants to build a $5 billion development in the Gulch; South Carolinians want to rebuild the Underground; and a German company has bought dozens of old buildings with the aim of recreating the downtown of old.

During my research I learned that out-of-towners eyeing opportunity south of Five Points is nothing new.

In 1984, some Singapore investors wanted to gobble up a 19-block area of South Downtown for a billion dollars. Then-Mayor Andrew Young, who later revived the Underground (for a while, at least), pushed hard for locals to sell to the foreign group.

Habif agreed with the mayor, telling the AJC: “If this doesn’t take place, I don’t see anything happening in my lifetime of any major consequence.”

That plan fizzled out and the deal of Habif’s lifetime flitted away. Unless …

I called Habif Properties and soon was talking to the man himself, who is now 91 and has lived long enough to see another Deal of a Lifetime roll along. Habif is a small, spry fellow who comes to work every day, still looking for ugly-duckling opportunities.

Habif is a vanishing connection to an era when hardworking merchants toiled in family-run businesses on Atlanta’s near-south side, the city’s original center. There were retail shops that grew into department stores, there were plenty of wholesalers and some small manufacturers.

“Jews had to make their own way,” said Habif, a Sephardi Jew whose family came from Turkey. “They wouldn’t hire you in many Atlanta companies. We knew that growing up. There was discrimination. So you found a need and filled it.”

Habif, the son of a haberdasher, attended Commercial High School on Pryor Street, and after classes did the books for a couple of nearby garment shops.

“They were manufacturers of dresses up on the second story of old buildings,” he said. “It was all ladies (sewing in those shops). It was like the sweatshops in New York.”

The area housed numerous clothing and apparel wholesalers and, said Habif, “the merchants from the small towns would come into Atlanta to replenish their supply.”

David Roos, a contemporary of Habif’s whose family has operated a store display and fixture company for nearly a century, told me that retailers from the “country” would flood Atlanta on Wednesdays and Thursdays to restock.

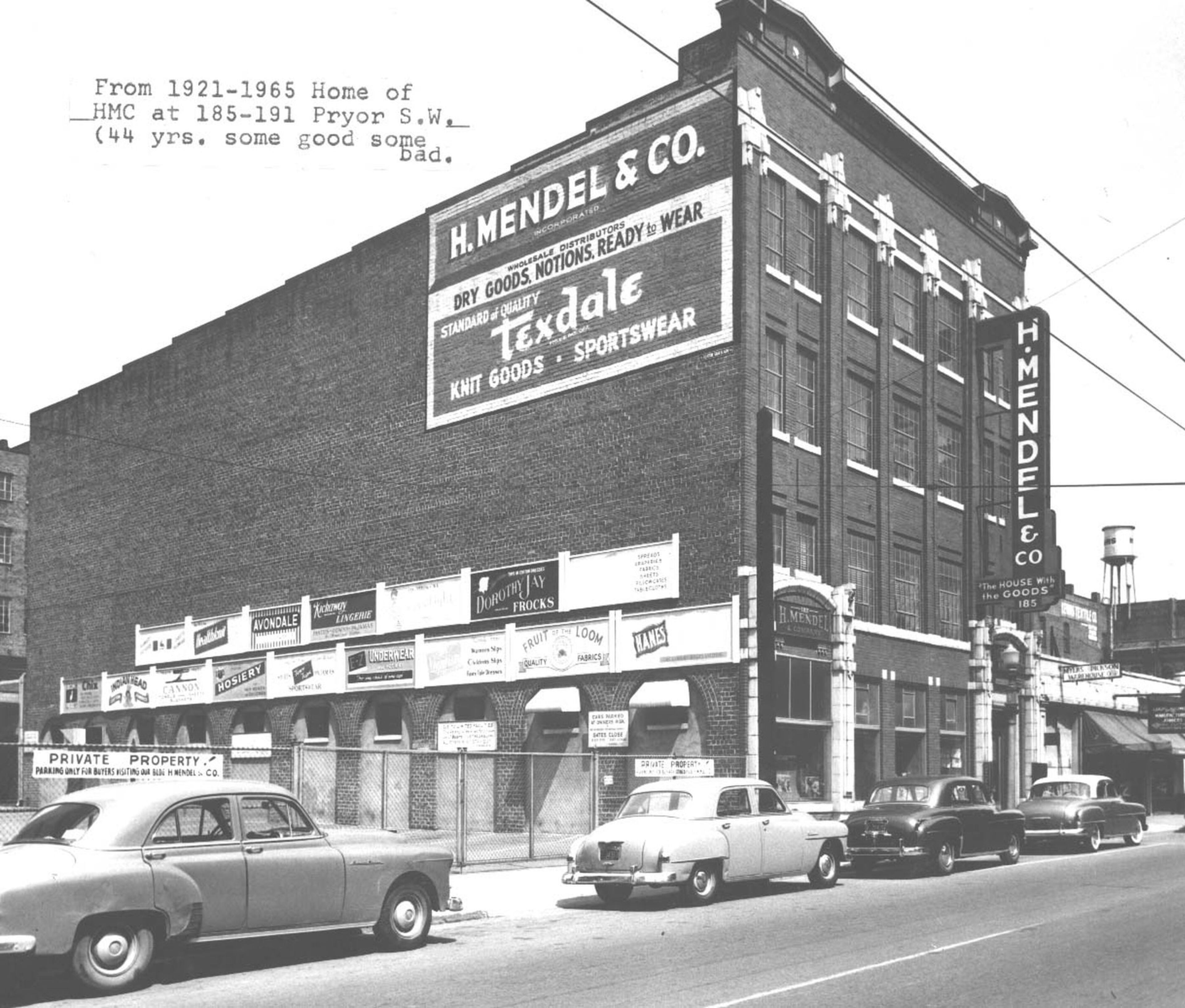

In the 1960s, Roos said the owners of H. Mendel & Co., a large clothing wholesaler on Pryor Street, bought land on Fulton Industrial and moved to larger digs with more loading room and ample warehouse space. Most of the other wholesalers nearby followed.

Habif had moved his distributorship to Garnett Street in 1965 because he got a great deal on space. And then he started buying up vacated properties, including the Mendel property.

The area “was depressed; the city didn’t seem to care,” said Habif. “Anytime someone wanted to sell, they had to come to me. I was the only one buying.”

He ticked off the names of streets where he bought land — Forsyth, Peachtree, Central, Mitchell, Broad and Pryor. He was good at squeezing income out of unwanted assets, either renting out space to artists, lawyers and bail bondsmen or tearing down dilapidated buildings to create parking.

“One of my best skills is finding tenants,” he said as we drove around South Downtown. “People wouldn’t know what to do with a building, so I’d buy it.”

In the early 1980s, he and other investors bought the vacant Southern Cross Bedding C0. factory near Oakland Cemetery and rented out space to small businesses and artists. It is now the Mattress Factory Apartments.

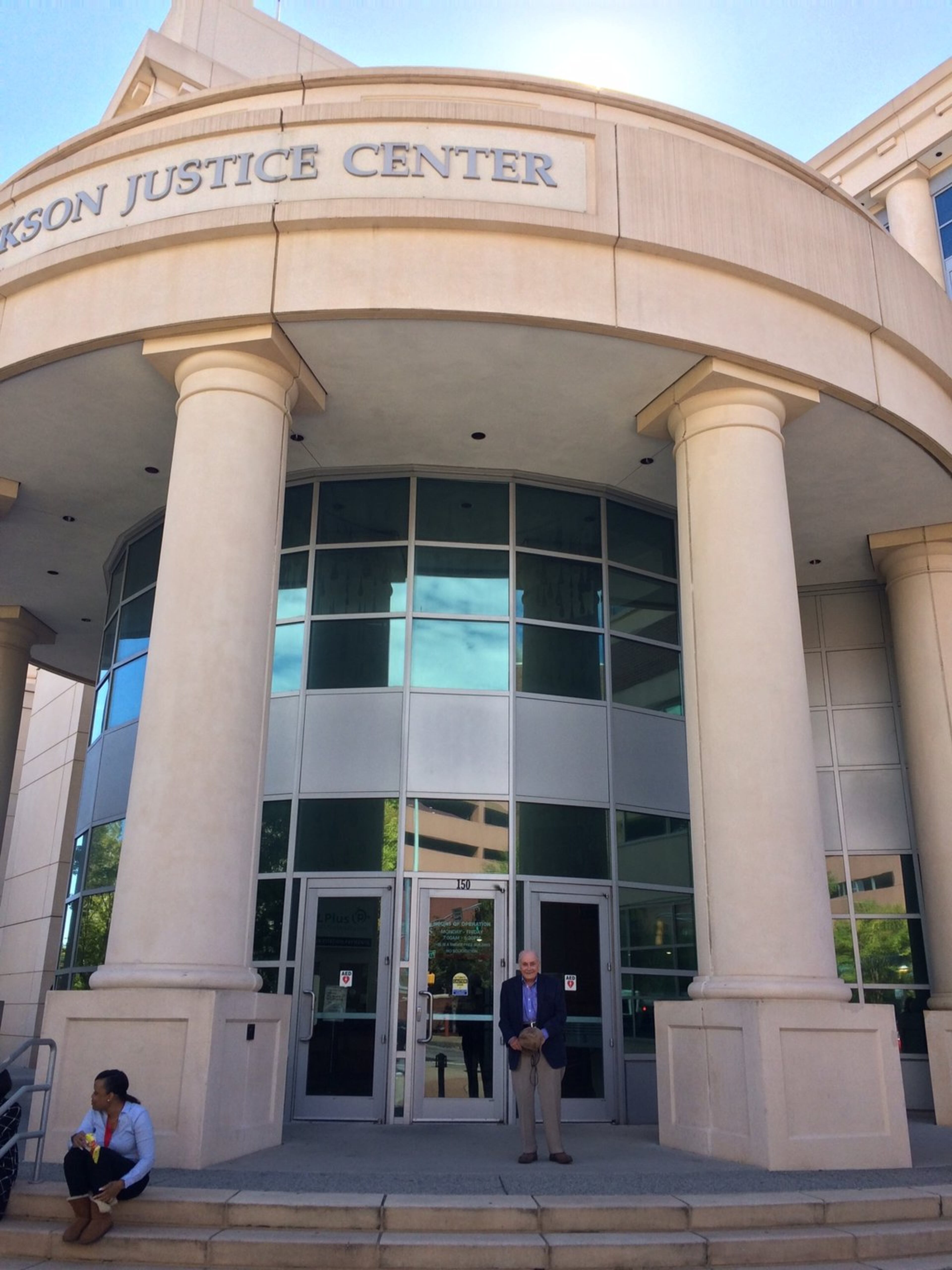

Years ago, he assembled a square block of properties to sell to the city for what is now the Municipal Court.

He pointed across the street to the police headquarters, which is built taller than other buildings and employs a forbidding architecture.

“They turned this into a fortress,” Habif said. “It’s another missed opportunity.”

Another property he bought decades ago in the Memorial Drive area near the Beltline not long ago brought him a king’s ransom. And a couple of years ago, he sold a former shoe factory at the corner of Pryor Street and Trinity Avenue to a developer who turned the large brick structure into lofts.

He's happy to see the sprigs of growth coming to life in South Downtown, although the area still suffers from crime, rampant homelessness and a lousy reputation. (A developer last week chided me for highlighting a multiple shooting that occurred in the area.)

I asked Habif how he figures the new efforts will go. He smiled and shrugged. He likes the momentum he sees and the possibilities. But he has been around long enough to know there are no sure things.

Maybe he’ll see something in his lifetime after all.