‘The Weeping Time’: Largest sale of enslaved blacks in U.S. history

The young mother stood on the auction block, her shawl covering the 2-week-old daughter she held in her arms. Next to her stood her husband, Primus, and their 3-year-old daughter, Dido. Daphney, the young mother, held the baby close, the infant’s cries piquing the interest of an agitated, jeering crowd of white men standing in front of the family.

“What’s the fault of the gal? Ain’t she sound? Pull off her rags and let us see her,” one man called out.

“Who’s going to bid on that (n-word) if you keep her covered up. Let’s see her face,” said another.

Daphney did not remove the blanket, even as the crowd became more profane.

The family stood in a cold rain at the open-air Ten Broeck Race Course grandstand outside Savannah, waiting for one of those men to decide their fate. Would the family remain together or be sold one by one to different buyers? The decision had to be made swiftly, because there were 432 more enslaved black people who had to be sold that morning.

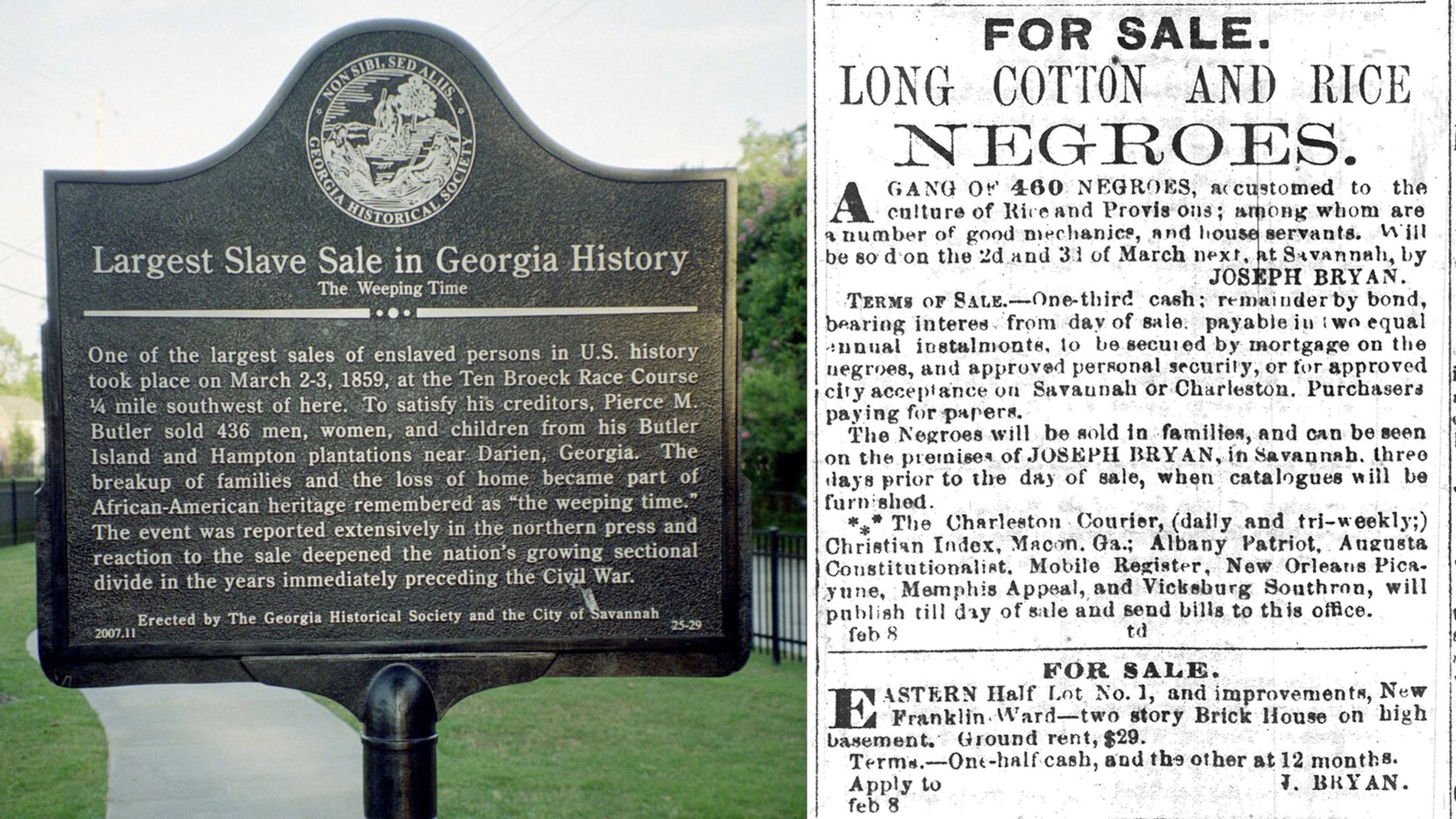

That day, March 2, 1859, is known as “The Weeping Time,” the largest, single-day sale of enslaved black people in the nation’s history.

The account of Daphney, Primus and their two daughters comes from Mortimer Thomson, a New York Tribune reporter who went undercover to write about the sale. He went by the pseudonym Q.K. Philander Doesticks. Thomson’s remains the definitive account of what happened that day in Georgia 160 years ago when black families — infants, mothers, fathers, children, young couples and the elderly — were sold to settle the debts of the man who owned them, Pierce Mease Butler.

The Butler family descended from Pierce Butler, a founder of the United States and author of the fugitive slave clause written into the Constitution. It required anyone who escaped from “labor” in one state to be captured and returned to the state and owner from which he or she fled. Butler had plantations along coastal South Carolina and the Georgia Sea Islands.

» RELATED: Sally Hemings: Mother of 6 of Thomas Jefferson’s children was also his property

» RELATED: Cudjoe Kazoola Lewis: Last known survivor of Atlantic slave trade

» RELATED: Phillis Wheatley, America’s first black published poet

Pierce Mease Butler, named for his famous, prosperous grandfather, then squandered much of his family’s fortune on gambling and the high life. The descriptions of the people put up as inventory during the 1859 sale tell the story of how African labor in the Butler cotton and rice fields built that family’s wealth, and how the younger Butler planned to recoup it.

“Emiline, 19; cotton, prime young woman. Sold for $400”

“Charlotte, 22; rice, prime woman. Sold for $750”

“Infant, 3 months. Sold for $700”

And on it went, 436 times, over two days.

Southern papers advertised the pending sale for weeks. Abolitionists decried it as an example of the evils of chattel slavery. Slave traders and brokers came looking for bargains.

“There were some thirty babies in the lot; they are esteemed worth to the master a hundred dollars the day they are born, and to increase in value at the rate of a hundred dollars a year till they are sixteen or seventeen years old, at which age they bring the best prices,” Thomson wrote.

A middle-aged couple, Anson and Violet, considered past their prime, were purchased for $250 each.

Daphney, Primus, Dido and her baby sister were sold together for $2,500, but with no guarantee that their new “owners” would not sell them individually when the girls grew older.

At the end of the sale, people were loaded up and carried off to plantations and homes across the South. But before they departed, Thomson wrote, Butler handed out a few coins to some of them, a perverse attempt at “solacing the wounded hearts of the people he had sold from their firesides and homes.”

Once they were all gone, many never to see each other again, Butler celebrated his windfall of $303,850, just under $9 million in today’s dollars. He and his broker who arranged the sale toasted with Champagne.

BLACK HISTORY MONTH

Throughout February, we’ll spotlight a different African-American pioneer in the daily Living section Monday through Thursday and Saturday, and in the Metro section on Fridays and Sundays. Go to AJC.com/black-history-month for more subscriber exclusives on people, places and organizations that have changed the world, and to see videos on the African-American pioneer featured here each day.

2019 COMMEMORATION

On March 2, there will be a 160th anniversary commemorative service at the site of “The Weeping Time” sale in Savannah. Organizers plan to set up 436 empty chairs on the site, which is adjacent to Otis J. Brock III Elementary School, 1804 Stratford St. Names of those sold will be called out during the ceremony. The service begins at 10 a.m. www.oceans1.org for more information.