The secrets of the death penalty

In the shadow world of Georgia’s death penalty, a doctor who is not practicing medicine writes a prescription for a patient who is certain to die.

The doctor’s role in this part of the execution process is shrouded in secrecy and wrapped in contradiction, an examination by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has found.

The doctor violates the canon of medical ethics simply by issuing the prescription, so the state has rewritten the law to stipulate that the doctor is not practicing medicine when prescribing an execution drug. If the doctor’s name were to get out, lawsuits and harassment would probably follow, so the state has declared the doctor’s identity — and any document that includes his name — a “state secret.”

The killing drug is pentobarbital, a barbiturate commonly used by veterinarians to euthanize dogs and cats, but manufacturers refuse to sell it to states for executions. So the drug must be created by a “compounding” pharmacist, whose identity is also a state secret, and sold to the Department of Corrections.

The only way for the state to legally obtain pentobarbital, however, is to have a doctor prescribe it. For this reason, court records show, the Department of Corrections hires a physician on a contract basis to write those prescriptions. (Yes, the contract is also a state secret. The state would not even provide a copy with all the names redacted to the AJC.)

The prescription itself apparently resembles most others. It spells out the drug and the dosage and contains the name of the “patient” — the state’s instructions identify the condemned as a patient — plus his birthdate, Social Security number and address on death row. But it also concludes: “Administer as ordered per execution order.”

The state has blacked out this process for obvious reasons: public disclosure of the doctor’s identity would expose him or her to lawsuits and harassment by anti-death penalty forces, as well as possible sanctions within the medical profession.

For example, most records relating to the execution of Kelly Gissendaner last month are locked away. But the AJC has found partial records from an earlier case, that of the last man executed in Georgia. These documents include a redacted copy of the state’s contract with the doctor: he or she was to be paid $5,000 a year to write prescriptions for lethal injection drugs. The state also provided a reserve fund of up to $50,000 for legal representation and up to $3 million in liability insurance should the doctor’s identity be revealed and lawsuits follow.

‘It’s wrong for a doctor to do that’

Whether the doctor is known or not, however, medical experts question the ethics of a physician prescribing an execution drug — or a pharmacist filling a prescription for one.

“It’s wrong for a doctor to do something like that – to help take someone’s life,” said Stephen Brotherton, a Texas surgeon who chairs the American Medical Association’s Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. “It’s against the guidelines of the AMA’s code of ethics for a doctor to do that.”

John Banja, a medical ethicist at Emory University’s Center for Ethics, sees arguments on both sides of the issue.

“Physicians are licensed by the state, and if the state believes there’s a legitimate reason to carry out an execution, I do not have an objection to physicians participating if it doesn’t violate their conscience,” Banja said. “If it is in the public interest to have the death penalty, it would seem to me to be legal for them to participate.”

He then added, “But whether it violates the Hippocratic Oath, that’s another question.”

Under the oath, which dates to the 5th Century B.C., physicians have sworn for millennia: “To please no one will I prescribe a deadly drug.”

A court motion filed last year by lawyers for a former death-row inmate contends the practice violates state and federal law.

The doctor “is merely performing data entry in the prescription pad that he or she has sold to (Corrections) for $5,000,” the motion said.

‘How else would you get the medication?’

Lawyers from the state attorney general’s office have countered that the prison system’s procurement of lethal-injection drugs is legal. In court filings, they cite the 2000 Georgia law that replaced the electric chair with lethal injection as the state’s mode of execution. That legislation says the “prescription, preparation, compounding, dispensing or administration of lethal injection … shall not constitute the practice of medicine or any other profession relating to health care.”

For this reason, regulations regarding prescription drugs do not apply, state lawyers assert.

Michael Madaio, who chairs the Department of Medicine at the Medical College of Georgia in Augusta, said the state’s argument “doesn’t seem entirely correct.”

“But how else would you get the medication?” he asked. “And if you believe in capital punishment and you’re a physician hired by the state and it’s your job, I guess that’s what you have to do.”

When asked about the medical ethics of writing prescriptions for lethal-injection drugs, Madaio said, “It’s certainly not something I would do.”

Under legislation passed in 2013, the names of all those who help prepare for an execution are shielded from public view. In upholding the law last year, the Supreme Court of Georgia said there are good reasons for the secrecy law. If the names are publicly disclosed, “there is a significant risk that persons and entities necessary to the execution would become unwilling to participate,” the court said.

‘Such information is a classified state secret’

The AJC recently filed an Open Records Act request for the current contract the state Department of Corrections has with the prescribing physician. When that was denied, the newspaper filed another request to the agency, asking for a redacted copy that shielded the physician’s name and any other identifying information.

That request was denied as well.

“Because (Corrections) believes that the entire record containing such information is a classified state secret, it lacks the legal authority to release redacted copies of the document,” Errin Wright, the agency’s assistant counsel, told the AJC in an email message.

The secrecy law was enacted after Georgia and several other states with capital punishment scrambled to find lethal-injection drugs because pharmaceutical companies refused to let their drugs to be used for executions. In Georgia, the prison system has turned to a compounding pharmacy to get its supply of pentobarbital.

Under the Controlled Substances Act, pentobarbital can only be obtained with a valid prescription because it is a Schedule II drug. And Georgia law says a licensed physician can prescribe a controlled substance “for a legitimate medical purpose” and when the doctor is “acting in the usual course of his professional practice.”

Last year, lawyers for condemned inmate Tommy Waldrip argued that the state was fraudulently obtaining pentobarbital because those conditions were not being met. But Waldrip’s litigation became moot when the State Board of Pardons and Paroles granted him clemency in July 2014.

In their court filing, Waldrip’s lawyers attached documents obtained from the Corrections Department by death-penalty lawyers representing another death-row inmate, Warren Hill. These records offer a glimpse of the arrangement between the prison system and the doctor who writes the prescriptions.

‘Just wanted to give you a heads-up’

One document, a draft “professional services agreement,” says corrections would pay the doctor $5,000 for services rendered from July 1, 2013, to June 30, 2014.

The documents also include a number of email exchanges from a corrections official to the pharmacy and the prescribing doctor in July 2013, about six months before Hill’s execution in January. The names of those sending and receiving the emails were redacted.

In one, the corrections official told the doctor that the pharmacist had just let the agency know what had to be on the prescription, such as the name of the “patient.”

“I will be happy to forward this information along to you when you are preparing to write the prescription,” the official wrote. “I just wanted to give you a heads up.”

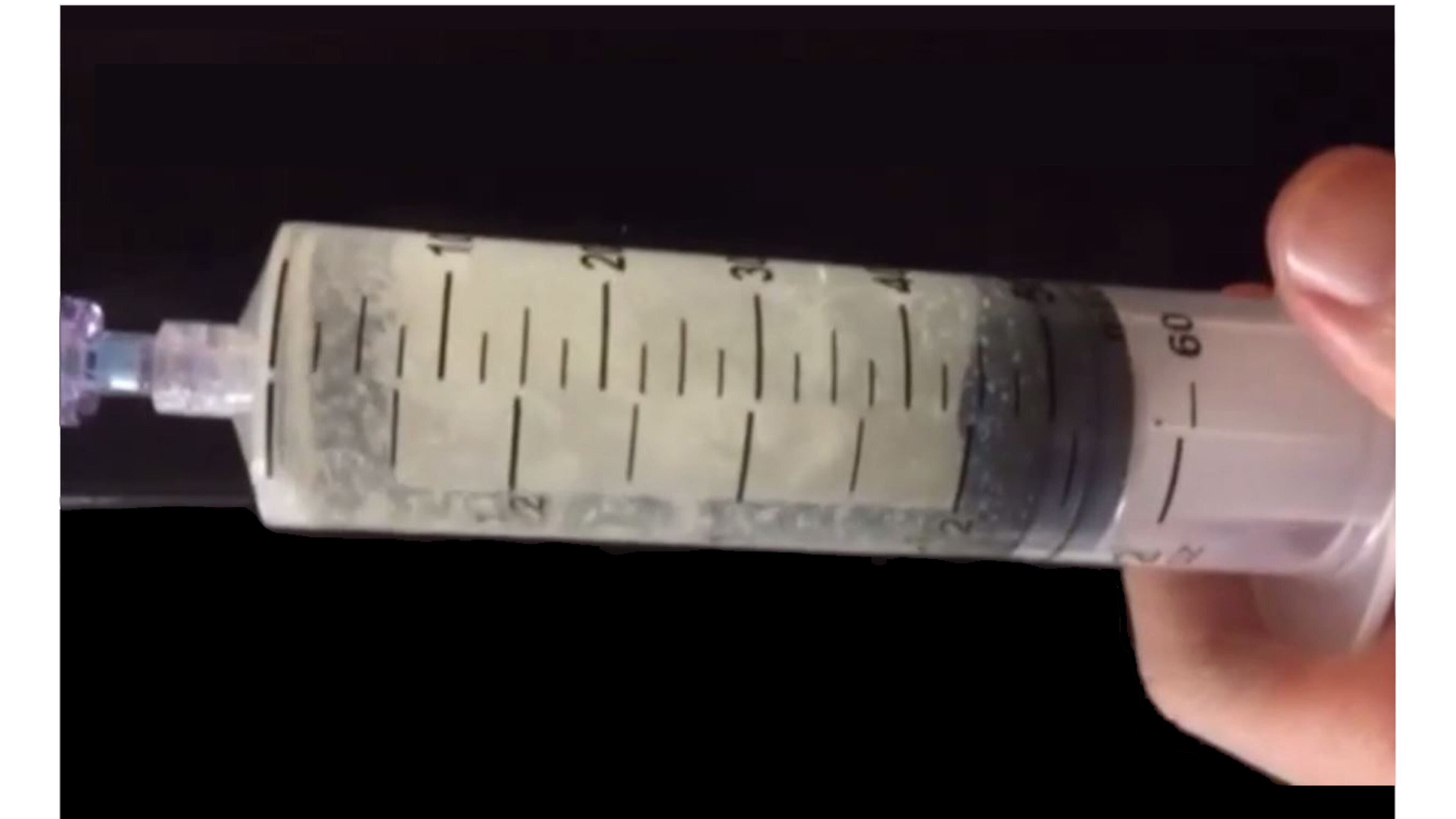

An email the next day instructed the doctor that, in addition to listing the patient’s name, birthdate, Social Security number and address, the prescription should call for 50 milligrams of pentobarbital solutions and six syringes. The prescription’s directions should say: “Administer as ordered per execution order.”

‘Georgia is saying two contradictory things’

The U.S. Supreme Court has not addressed the issue of whether doctors may lawfully prescribe an execution drug. But a decade ago, the high court ruled that then-U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft could not threaten to revoke the licenses of Oregon doctors who prescribed lethal doses of medication to help terminally ill patients end their lives.

Ashcroft contended the Controlled Substances Act required every prescription for a Schedule II drug to be issued “for a legitimate medical purpose (and) in the course of professional practice.” In a 6-3 ruling, the Supreme Court held that Congress never gave the U.S. attorney general the “extraordinary authority” Ashcroft claimed he had.

Robert Atkinson, the state attorney who argued the case, noted that Oregon’s Death With Dignity Act considered assisted suicide to be a valid medical procedure. He questioned whether Georgia could prevail in the dispute about prescriptions by simply declaring lethal injections is not the practice of any profession relating to health care.

“It seems to me that Georgia is saying two contradictory things,” said Atkinson, who is now retired. “It’s saying that writing prescriptions for lethal injections is not the practice of medicine, while only those who are engaging in the practice of medicine can write prescriptions. How do you reconcile that?”