Teachers try to fill academic, skills gap

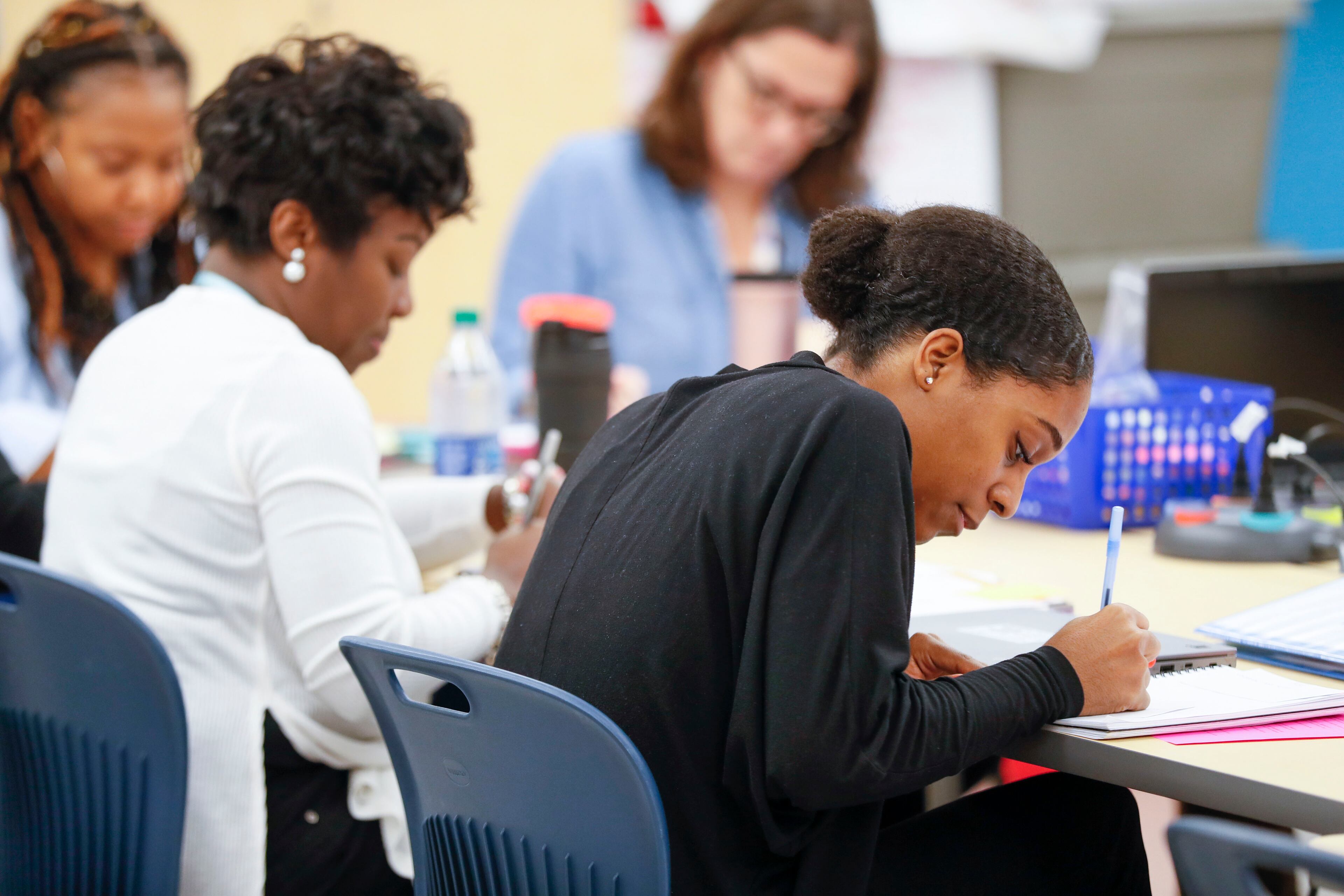

Even before the first phonics lesson or test, teachers at Harper-Archer Elementary marched to a drumbeat: Get better, get better, get better.

The school already bore the “turnaround” label when it opened in August. The designation was also a mandate.

Towns and Fain elementary schools, whose closures led to Harper-Archer’s creation, had both appeared on Atlanta’s turnaround lists before. Fain, particularly, struggled with large numbers of students who were behind in reading and math.

So much depends on a student’s first few years in school. It’s when they build the academic bedrock they need to be successful and graduate from high school. It’s when they begin to love and value education.

“That’s the only way that kids have a chance to choose the life that they want to live,” said Principal Dione Simon Taylor. “Because of that, then Atlanta will be a better place to live.”

VIDEO: ‘It takes every single one of us’

Closing the gap in reading

Most Harper-Archer students aren’t reading at grade level, so the school had to craft a strategy to try to catch them up. Educators also needed to be agile and flexible, shifting quickly when things don’t work.

About two months into the school year, after analyzing student data, the leadership team sharpened its focus on lower-elementary grades.

The public assessment of a school’s strength is based largely on scores from state tests, which students begin taking in third grade. But large gaps can develop in younger grades, and Taylor said kids’ future success hinges on helping them earlier.

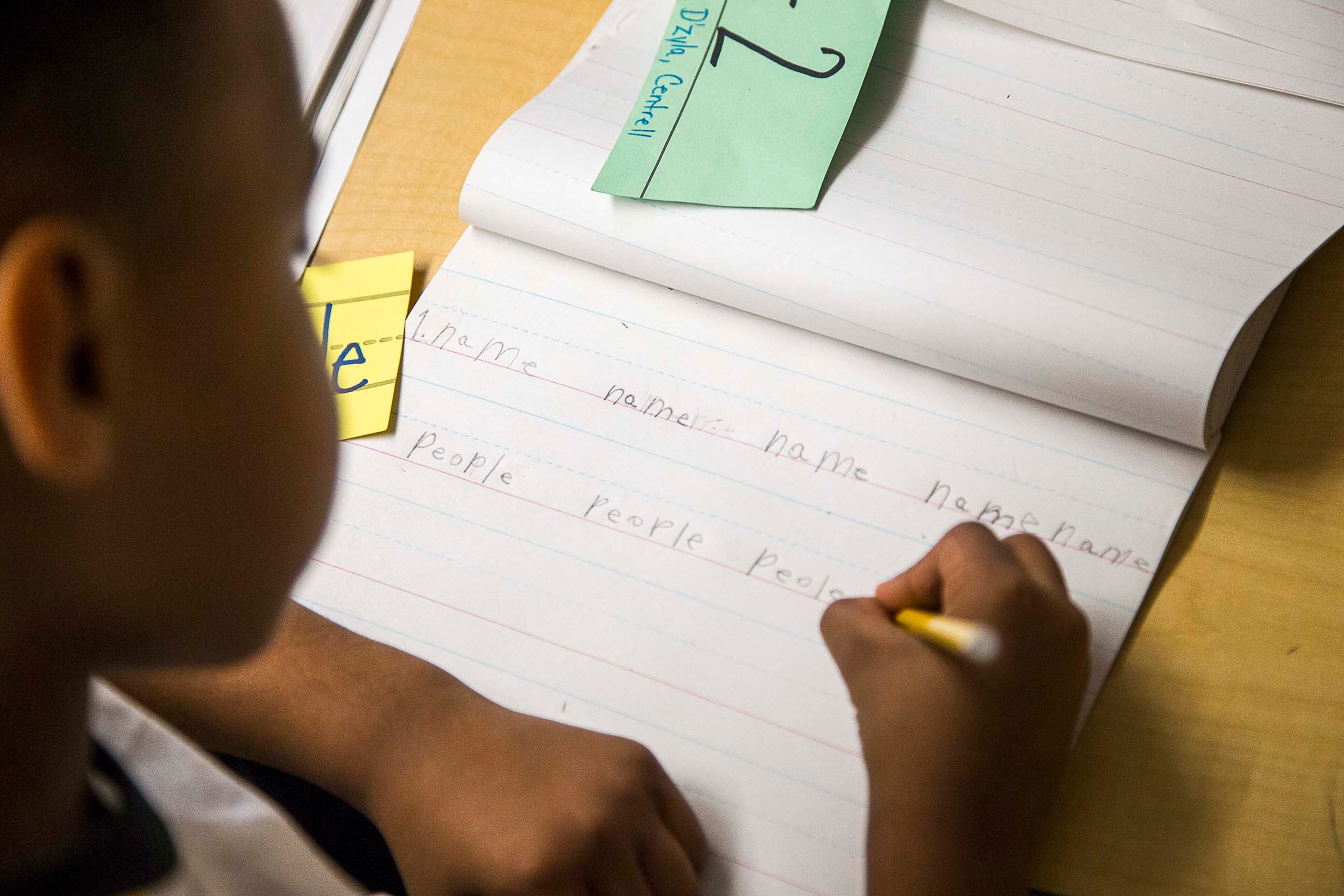

Many Harper-Archer students live in poverty and enter school without foundational knowledge. Some can’t recognize letters and don’t know the sounds they make.

Their oral language skills are under-developed, and they’ve heard far fewer words than students from more affluent families, said Justin Browning, a former elementary teacher turned instructional coach who supports the school’s kindergarten and first-grade teachers.

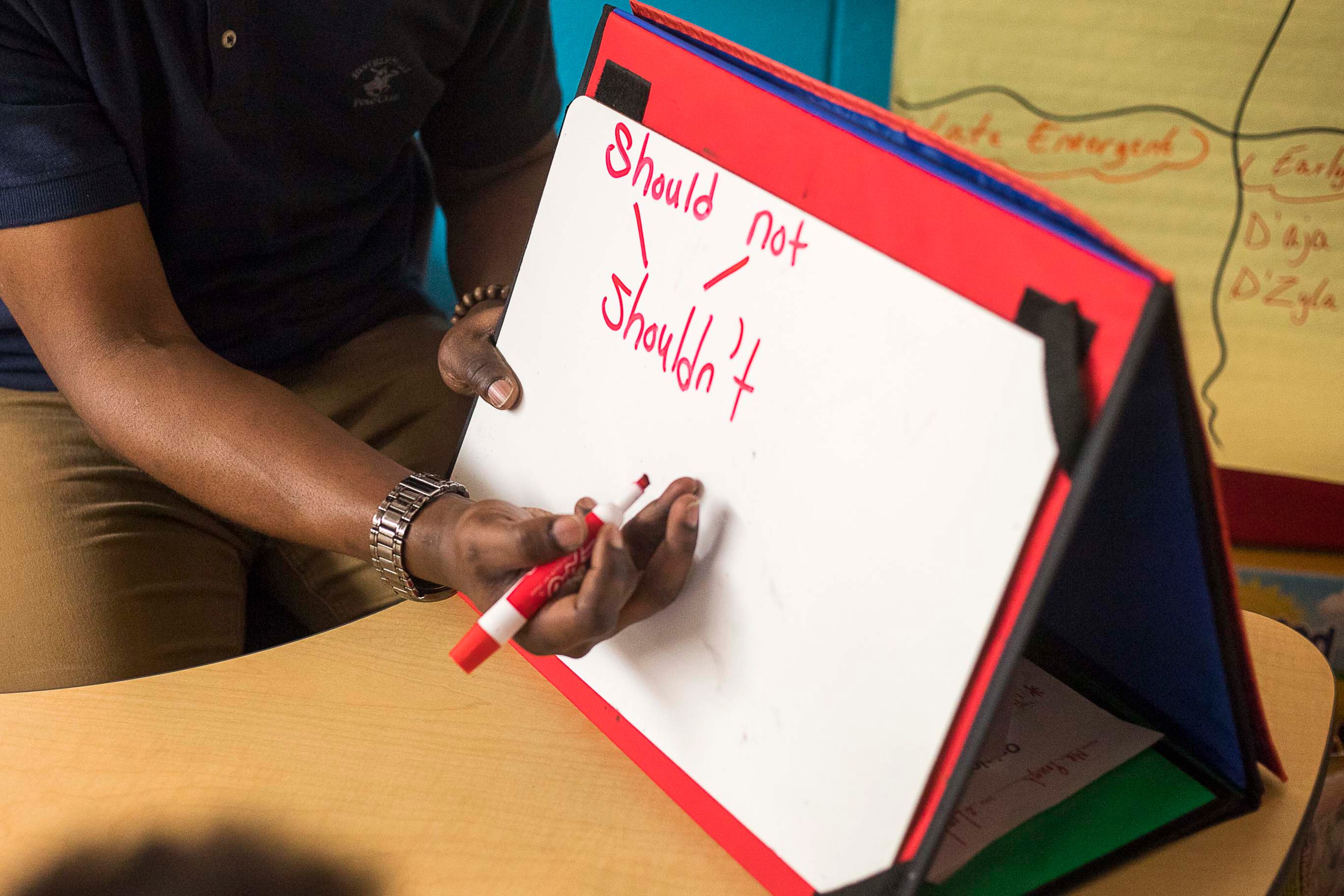

During a weekly meeting with teachers back in October, Browning asked if students need more time to master a reading concept before moving to the next one. Yes, said the teachers.

Taylor and her team have leaned hard into kindergarten and first grade classrooms. Investing in early grades and fostering good habits in younger children is generally viewed by turnaround experts as a solid investment.

“If we can really get it right in the younger grades, then we have the opportunity to change the trajectory of our school, but not just the trajectory of our school but the trajectory of their lives because literacy is foundational to success,” Browning said.

Harper-Archer adjusted schedules to spend more time reading and calling out words, exposing children to text and working in smaller groups to address individual students’ specific needs.

Teachers still weave in social studies and science, but reading is at the core.

Instead of chasing state standards that spell out what students should know in specific grades, teachers focus on the building blocks of literacy.

“We already know they’re coming to school for the most part behind everyone else just because of the vocabulary that’s being used in the home,” Taylor said. “Our bold move was to step back.”

In lower grades, the school decided not to give some of the district’s optional benchmark assessments that aim to measure if students have learned standards. Taylor has found those assessments mostly test students’ listening skills and not whether they’ve learned the material.

Teachers would test students quarterly to see if they’re learning more sight words and give them literacy screeners to make sure they’re moving in the right direction.

At a January parent night, first grade teachers explained that they want to be realistic about where students are, instead of expecting them to summarize a story before they can even read the words. But they also want to challenge students and set goals so they are always improving.

‘Something we’re building ourselves’

Step into BryAndra Bell’s classroom, and the emphasis on reading is apparent. Baskets of books line the shelves, and an illustrated alphabet — A with an apple, B with a bat — stretches across the front wall.

After lunch one fall day, her first graders settled onto the colorful carpet to review high-frequency words displayed on a big screen. They rattle through a list lickety-split: He, his, has, have, is.

When a child flubbed a word, Bell didn’t miss a beat: “Don’t worry. You’re smart. You’re going to get it.”

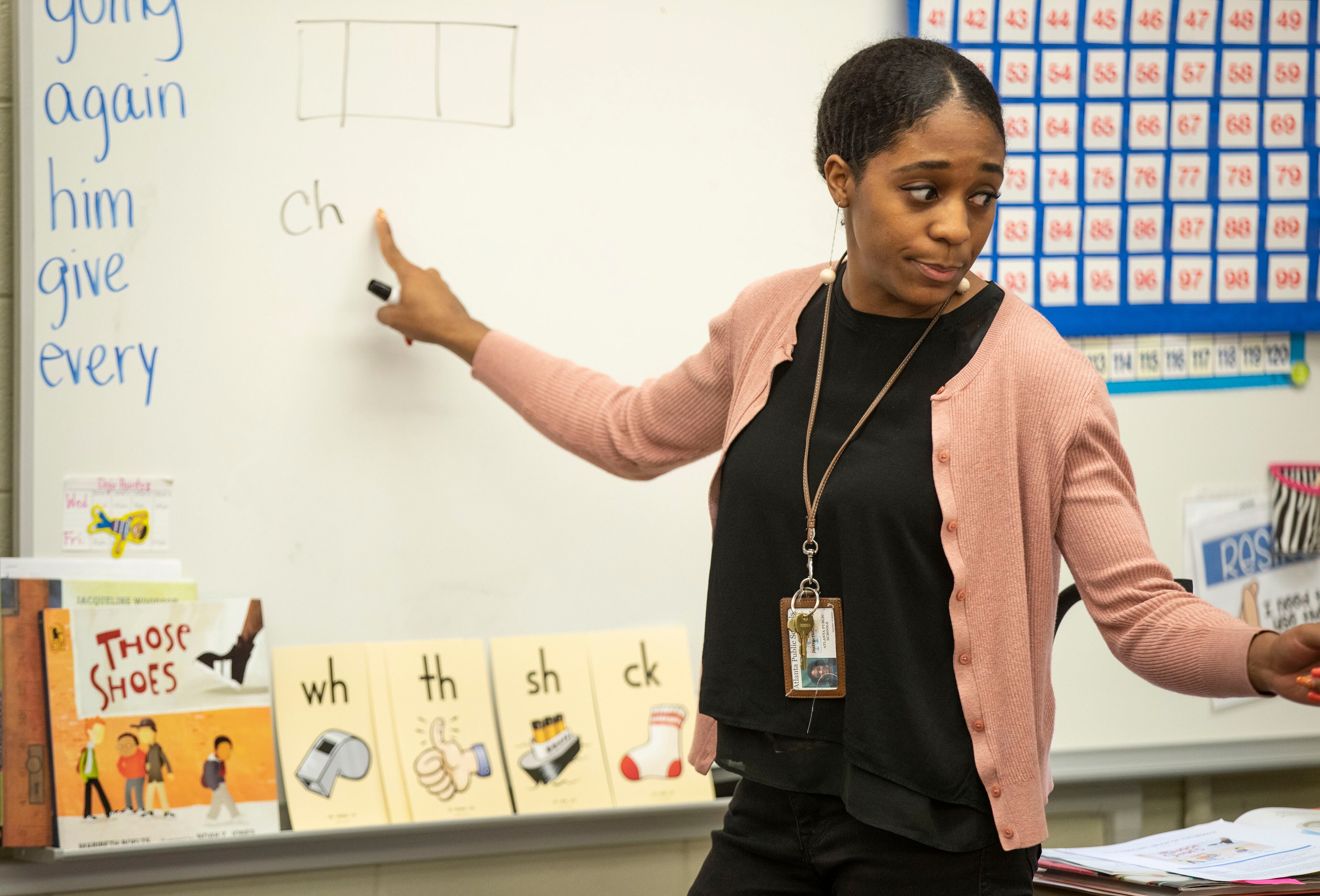

The teacher went over blending sounds and reviewed digraphs — two letters in combination that make one sound, like “sh” in ship. Everything in Bell’s lesson has a rhythm, a clip she maintains with finger snapping and frequent reminders that the words need to be fluent.

This is Bell’s sixth year of teaching and first in Atlanta Public Schools. She was drawn to the Harper-Archer job in part because the school had just opened.

“We’re all able to contribute to something that we’re building ourselves,” she said. “It’s having the opportunity to create something new and start something fresh.”

Bell said the decision to add a “double dose” of phonics has been helpful. It gives her more time to hear children reading words and teach them sounds.

Fellow first-grade teacher Jocelyn Davis said her students came in with various reading abilities. Devoting more time on foundational skills has made a difference. “I can see movement now that we’re doing that. It’s impactful, and it’s meaningful,” she said.

If it doesn’t work, change

Taylor isn’t afraid to make changes when she sees something isn’t working.

Though major instability hinders turnaround efforts, research also shows that adapting and improving teaching strategies can help.

The school shifted the phonics lesson to later in the day in some second-grade classrooms because too many students were arriving late and missing that crucial instruction.

Most fifth graders started the year taking math and science from one teacher and then switching to another classroom for English language arts and social studies.

Weeks into the school year, Taylor decided it wasn’t working. Students were losing too much instructional time as they moved from one class to the next, so she told teachers they would have to teach all subjects.

It wasn’t what they had expected to do, but she told them it was necessary.

“Once we got here and once we realized this doesn’t work, then we’ve got to change because otherwise we are just setting ourselves up to fail,” she said.

In some schools, students just don’t have the same foundation for learning as others. It’s a problem Atlanta’s school district has been confronting for generations, and the district has been in a multiyear, multimillion-dollar project aimed at helping.

Some steps, such as turning six schools over to charter groups to run, have been controversial and watched nationally, since educational inequity is a problem all over the country, not just in metro Atlanta.

Teachers know that whatever they do in the classroom, they can’t control some factors – parental involvement and generational poverty, for example – that have powerful influence on their students’ ability to learn. Atlanta’s results so far underscore just how difficult turnaround is. Schools have seen some gains, but there’s minimal evidence it’s because of the turnaround investments.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution wanted to know: Just how does the school give students the proper education they’ll ultimately need to compete with their peers for adequate jobs, and to be responsible, productive citizens in our communities?

To answer that question, we knew we had to be in the classrooms and hallways of a school trying to find solutions to these challenges.

We knew we had to speak to community residents and parents.

The AJC asked Atlanta school officials to give us unprecedented access to a school being targeted for special attention because of its long-standing challenges.

Harper-Archer Elementary, the “turnaround school” the district selected when the AJC proposed this project, is new. The west Atlanta school opened this year to serve neighborhoods that are among the poorest in Georgia.

School officials allowed our reporter and photographers a close-up view of the people and the everyday goings-on in the life of that school community.

Over several months, AJC reporter Vanessa McCray and photographers Alyssa Pointer and Bob Andres spent many days observing, interviewing and recording the efforts and the motivations of the dozens of people who are trying to ensure that what’s in store in the lives of the children there can be brighter than their beginning.

Successful communities support and invest in the education of children. Strong schools use that support to set high expectations and to execute bold, cutting-edge initiatives.

Not every school in Atlanta can claim such success. For some city schools, the challenges seem too great to overcome.

Students at Harper-Archer Elementary School come to class each day from Atlanta neighborhoods struggling with the harmful side effects of generational poverty. They also suffer from inconsistent parental engagement and many of these children lack basic reading skills – the foundation for academic accomplishment.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution wanted to know, just how do teachers, principals, counselors, and other school staffers try to give these children the proper education they’ll ultimately need to compete with their peers for adequate jobs, and to be responsible, productive citizens in our communities?

Atlanta Public Schools gave the AJC unprecedented access to the inner workings of its efforts to turnaround this school. The stories inside this special section are the result of our reporter and photographers spending dozens of hours at Harper-Archer over several months.

If the folks at Harper-Archer are successful with their bold plans, the school will serve as a template for other urban schools struggling to meet basic standards.

We interviewed school leaders, teachers, community residents, and parents, to get the full picture of the magnitude of the challenge and of those who are trying to find solutions.

They are stories of determination and hope.

- Todd C. Duncan, Senior Editor Local Government and Education

As much as leaders try to anticipate, sometimes they are forced to adapt.

In late August, Taylor watched enrollment closely to see if they’d hit the projected 734 students, the number her budget was based on. She was nervous about “levelling” — the process the district uses to balance financial numbers with staff based on actual enrollment. It was one of her first big hurdles, and she ended up losing two teachers because enrollment, at that point, was about 100 students shy of expectations.

That challenge isn’t unique to Harper-Archer, and the district worked to make it as seamless as possible.

“But even two hurts when you’ve built these smaller classes, and now I’ve got to combine, and I’ve got to move services,” Taylor said.

As the school year wore on, Taylor battled attendance woes and an unprecedented closure because of coronavirus concerns.

She wove the arts into core subjects, a push that made Harper-Archer a pioneer among Atlanta schools. She also included the science, technology, engineering, and math — or STEM— program that’s a signature of westside schools that feed into Douglass High School.

First, build relationships

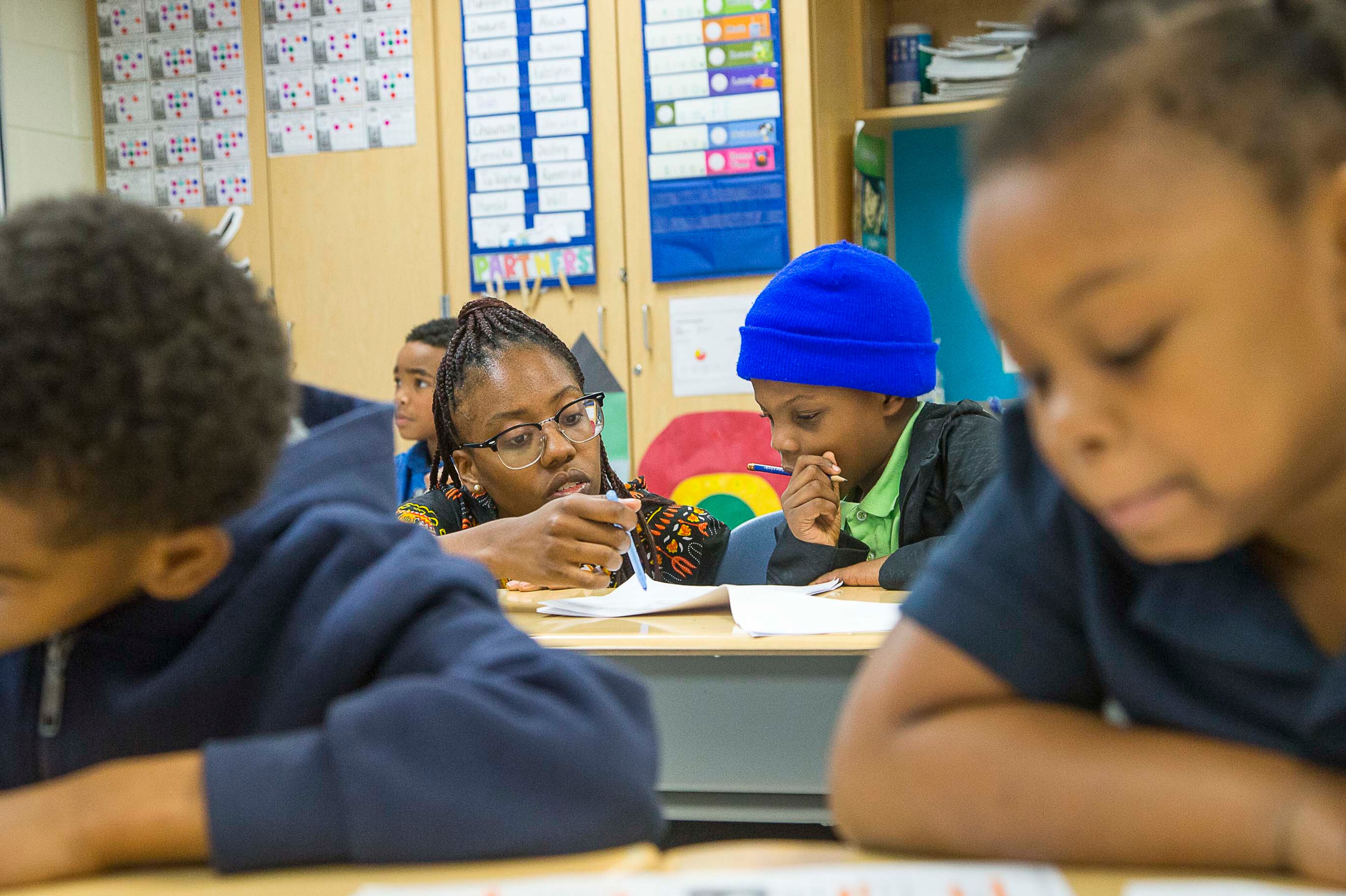

In a turnaround school where many students lag academically, some might expect teachers to immediately launch into drills and instruction. But fifth-grade teacher Alecia Westbrooks said her top priority in early August was to build a relationship with her students and their parents.

“You have to feel safe in here. You have to feel that you’re valued in here. It’s a lot of that that goes on before I even can say ‘one plus one is two,’ ” she said.

Students in her class are, on average, about three grades behind. Westbrooks said she’s building a culture in her classroom where students are willing to try, even if they struggle.

Students shouldn't dread school, and no child should crawl under a desk because they don't know an answer, as she had seen at Fain, where she previously taught. She said Fain staff worked hard to address behavior issues that diverted teachers' time and attention.

At Harper-Archer, she starts every Monday by asking kids what they did that weekend. That gives her insight into potential problems or emotions they might be bringing into the classroom.

Fifth-grader T’era Stewart described the school as a fun place with good vibes and lots of activities. Westbrooks “puts things in a way where it makes me understand,” she said.

During a social studies class one winter afternoon, students learned about food rationing in World War II. They assembled a grocery list based on a limited budget and a set number of ration points.

They had to figure out how they could afford balanced meals with fruit, vegetables, grain and protein.

“We’re not getting bread,” said one child, sparking a heated debate at his table.

Earlier, Westbrooks connected the lesson to concepts some of her students might be familiar with: food stamps and Women, Infants, and Children program benefits.

That effort to encourage kids, and keep them engaged, is evident in many classrooms. Third-grade teacher Keisha Johnson runs her classroom at a brisk pace — there’s no time to be bored or lollygag — and with infectious enthusiasm.

“Are you reading to learn?” she asked on an October morning. “Are you ready?”

The students responded with chants and cheers. When a child answered a question correctly, the entire class offered congratulations.

“Let’s give her the slam dunk,” Johnson said.

“Slam dunk, in your face,” the class replied in unison.

Johnson makes sure students who don’t know the answer get a second chance to respond and let’s them “phone a friend” at another desk for help.

Browning, the instructional coach, said his heart has grown softer for teachers this year. He knows the difficulty of the work they’re trying to do. Success depends on their ability to connect with kids.

“I think that the truth is that we can have the best program, we can have all the curriculum, we can have everything else in place, but … the one thing that makes all the difference is an effective teacher in the classroom,” he said.

» NEXT STORY: Dance students add rhythm, flow, joy to learning

Student achievement

Fain and Towns elementaries closed last year, and Atlanta Public Schools opened Harper-Archer Elementary in August to serve those students.

Percentage of students who scored proficient or above on state tests, or Milestones, in 2019:

English-language arts / Math

Fain: 6% / 8%

Towns: 19% / 25%

APS: 37% / 40%

Georgia: 43% / 47%

Source: APS