State to adopt Gwinnett’s model for developing school principals

About a decade ago, Gwinnett County school leaders realized that to find good administrators, of any race or ethnicity, and keep them in the community, the best practice was to develop them from within the district. Recruiting quality teachers that reflect the race and ethnicity of the student population had already been a priority.

Started in 2007, its Quality-Plus Leader Academy has been so successful that 88 percent of Gwinnett schools are led by its graduates, and the program will be a model for a new statewide initiative.

The effort fits the district’s goal of increasing diversity in school leadership. In the early years, most candidates were white females, but in the last two years, the program has attracted over 70 percent participants of color.

Gov. Brian Kemp’s office announced last week that the Governor’s Office of Student Achievement, Georgia Department of Education and Gwinnett County Public Schools have partnered to offer leadership training and one-on-one coaching to current and aspiring school principals through the new Governor’s School Leadership Academy.

Beginning with the 2019-2020 school year, 60 to 90 selected participants statewide will receive a year of training and support through a combination of in-person meetings, coaching and mentorship from a former Georgia principal, and opportunities to network with fellow principals. Like Gwinnett’s program, the goal of the GSLA is to strengthen leadership capacity – and the principal pipeline – in underperforming schools.

Gwinnett’s program includes a year-long instructional program led by the superintendent and other district leaders and a 90-day residency in a school to put participants in real-life scenarios.

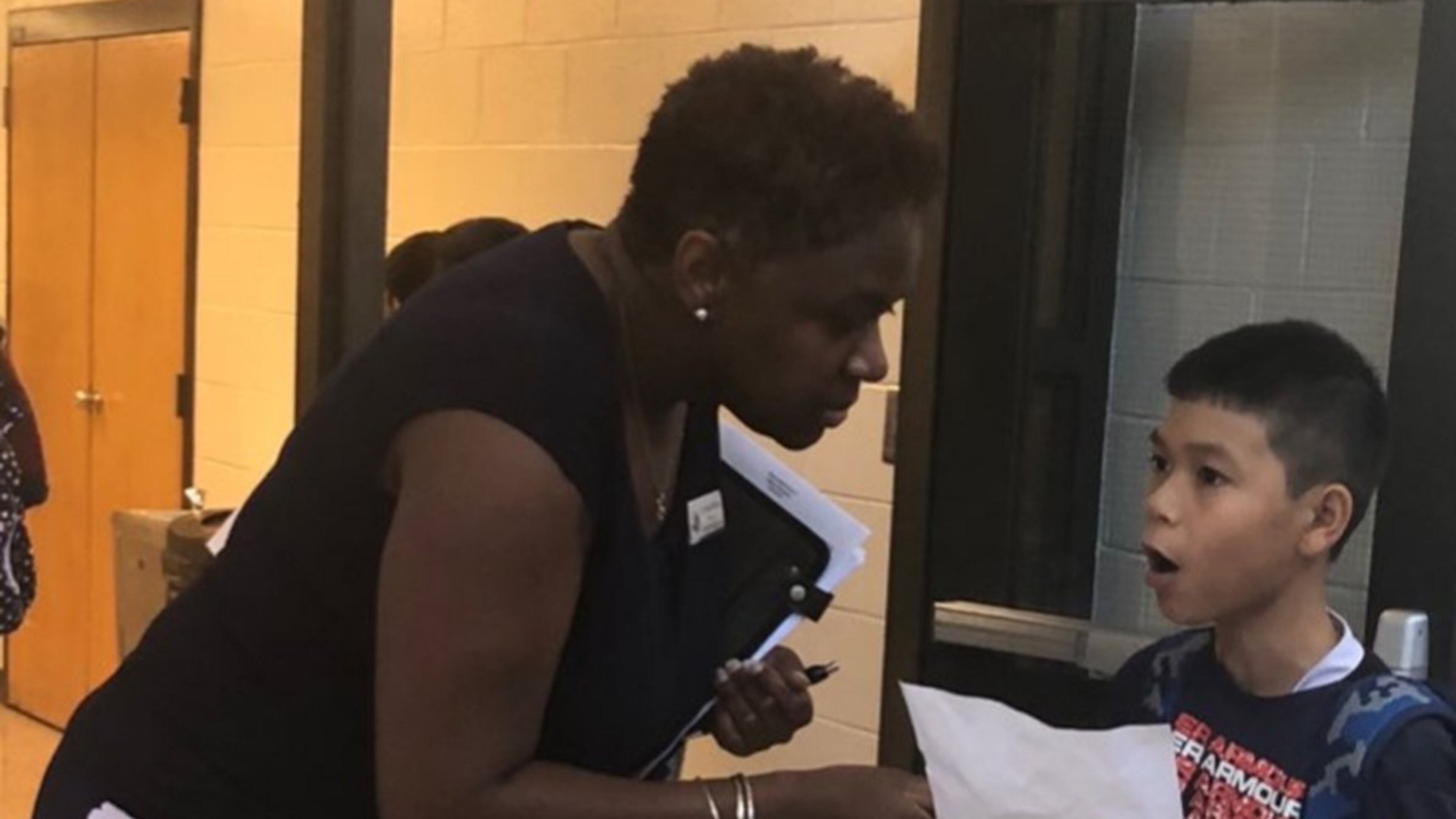

Tereka Williams, a Leader Academy graduate who is now principal of Shiloh Middle School, explained the rigors and rewards of the program at a recent school board meeting. She said it used role-playing to prepare her for meetings to share the school’s mission and vision with parents.

“My colleagues and the assistant superintendents asked probing questions and required the kind of answers parents and other stakeholders want to hear,” she said. “When I had to give the presentation for real, I was confident that I could provide pertinent information.”

She said, “Scenarios and simulations put you in the role of principal and we had to consider the decisions we would make in the given situations. In these experiences we learned that it is important to know yourself, know your job and know your people,” she said. “With each session our responses had more depth. We reached beyond the obvious and became more confident in our ability to present ourselves as well-informed leaders.”

Gwinnett’s model didn’t happen overnight. The Quality-Plus Leader Academy started with the Aspiring Principal Program and three years later, the Aspiring Leader Program came online to similarly prepare staffers for assistant principal roles. The two programs produced 475 principals and vice principals currently in those positions in Gwinnett. That’s 66 percent of program graduates. Another 19 percent are in other district or local school leadership positions.

But most of Gwinnett’s school leaders in training have been white, reflecting a fact of life for school systems across the country that’s a hurdle to increasing diversity in principals’ offices.

Gwinnett's student population went from 80 percent white in 1995 to about 22 percent today; about 31 percent of students now are Hispanic and about 32 percent are black.

As public schools increasingly serve more students of color, districts scramble to hire the best and brightest minority candidates. Data from the National Center for Education Statistics show, however, that in the 2015-2016 school year about 80 percent of all public school teachers were white.

Ongoing research from Harvard, Johns Hopkins and American University show that minority students who had one teacher of the same race or ethnicity by third grade were 13 percent more likely to enroll in college. Those who had two such teachers were 32 percent more likely to seek higher education because of the so-called role model effect. Schools acknowledge that it's also important for white students to have teachers of color in the classroom so they can see people from different backgrounds who are knowledgeable and can be role models for them, too.

In searching for those role models, "We're going after the same people that everyone else wants," said Sloan Roach, a spokeswoman for Gwinnett County Public Schools, the largest school district in the state and the 14th largest in the country.

“As we hire, (Gwinnett) continues to increase its concentration on recruiting from those teacher-preparation programs that have a high student minority population, including our recruitment efforts at historically black colleges and universities and colleges in Texas and Florida where we find more Hispanic/Latino education majors,” said Linda Anderson, associate superintendent for human resources and talent management.

“We also work closely with partner university teacher-preparation programs to host student teachers, specifically focusing on critical fields and minorities. In addition, we have grown our Teaching as a Profession program, which is found in our high schools as another means of growing our own teachers … teachers who not only are reflective of our community but who already have ties to it.”

Before catching the eye of Gov. Kemp, Gwinnett County was among six large school districts that received grants in The Wallace Foundation’s Principal Pipeline Initiative in 2011.

While recruiting future leaders among minorities remains a challenge, “Gwinnett is one of the rock stars of the principal pipeline,” said Beverly Hutton, deputy executive director of the National Association of Secondary School Principals. “They are good at building culture and relationships.”

Why it’s important

Finding good principals is a long-standing challenge for school districts nationwide. Gwinnett County’s rapid growth required more facilities and people to run them. Leaders were concerned that the bench wasn’t as deep as they needed. They began to seek out and cultivating the skills of people already in the system who might aspire to leadership roles, enlisting principals and district staff in the effort to grow leaders capable of leading instruction and thriving in a climate of strong accountability.