Remembering King: Classmates, colleagues recall influence

A classmate. A fraternity brother. A colleague in the American struggle for civil rights. A high school student. Their lives intersected with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Decades later, on the holiday celebrating King's life and the civil rights movement he led, these contemporaries of King recall how the young preacher from Atlanta influenced them.

Herman W. Hemingway, 79, Chestnut Hill, Mass.

Attorney and retired professor at the University of Massachusetts at Boston.

Hemingway first met King in 1952 when the two were Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity pledges. King was a doctoral student at Boston University. Hemingway was an undergraduate at nearby Brandeis University.

From the moment King walked through the door, said Hemingway, he stood out -- serious and erudite.

"The doorbell rang and here comes this short guy with very brown skin," Hemingway said. "And he's a reverend. He was older than the rest of us. We were teenagers. We wanted to have fun, joke around, tease each other. . . He kind of distinguished himself from the rest of the group."

King became the fraternity's chaplain and a father figure, Hemingway said. He recalled how they never called King by his first name, only "Rev" or "Brother King."

All pledges were required to remember a poem, William Ernest Henley's "Invictus."

"It exemplified how to deal with struggles and challenges and how to be self-sufficient," Hemingway said. "It seemed to be a dress rehearsal for things he was later to face."

How King influenced him: "I feel blessed to have met and spent time with Brother King. I was inspired by him as well. This was a man who was on a different wavelength than the rest of us.

"... We learned the importance of community efforts, brotherhood, self-reliance and respect for our own people. His contributions weren't specific but his participation with us was the message. His contribution to the group was to keep it real and to encourage us to hang in there until we accomplished our goals. The collective nature of his participation was the inspiring part."

Samuel DuBois Cook, 82, Atlanta

Retired president of Dillard University.

Cook and King were classmates at Morehouse College, both sons of Baptist ministers.

A friendship developed on the all-male Atlanta campus. King, as Cook remembers, was popular, outgoing and stylish.

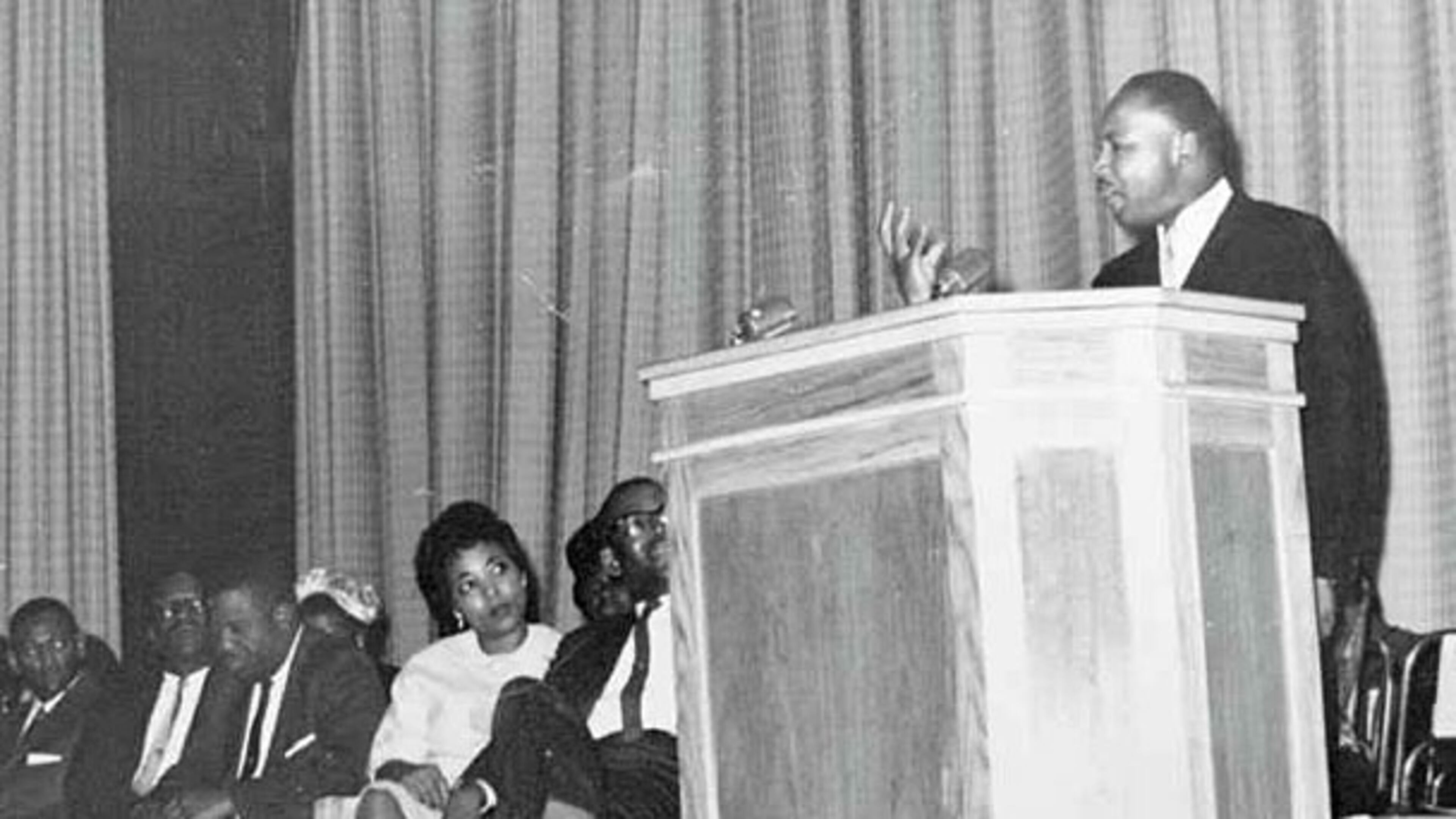

An unforgettable experience for Cook was hearing King give the senior sermon at Morehouse in 1948, where a young King displayed the oratory skill that would help transform the nation.

"I remember M.L. saying in that sermon that there are moral laws in the universe that we cannot violate with impunity any more than we can violate physical laws with impunity," Cook said. "He was talking about the moral order of the universe and our relationship as brothers in that universe. It was the most moving experience. It was a powerful, powerful address. He soared."

Cook and King remained friends until his death. Cook still chuckles at how during a holiday gathering -- in either 1966 or 1967 -- he and his wife struggled over whether to serve King eggnog with a little something extra.

"I told her don't just give ML this eggnog, put a little bourbon in it. She said, ‘No, you can't do that. You can't give him any bourbon,' " Cook said. "But she put a little in there. When she gave it to him he tasted it and said in his unique voice, ‘Sylvia, honey, I don't know what in the world you put in this eggnog but whatever it was put in some more.' "

How King influenced him: "The depth of his sincerity and his commitment to the kingdom of God had a great impact on me. M.L. was serious and sincere about social justice, about equality and about God. It challenged me. It made me want to be a better individual and to make a deeper commitment to the kingdom of God.

“That's what ML was about, really, the kingdom of God.”

Editor's update: Samuel Dubois Cook died in 2017

Dorothy Cotton, 81, Ithaca, N.Y.

Retired Dean of Students at Cornell University.

Cotton, as education director for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, traveled the country with King. She did so when the civil rights movement was at its peak. Danger lurked everywhere.

Cotton was in the traveling party that went to Memphis in April 1968. She was with King on his last plane ride.

Cotton was set to fly back to Atlanta on April 4, the day King was killed.

"I was eating breakfast in the restaurant, when he called for me," Cotton said. "His last words to me were ‘get a later plane.' But I had to get back to Atlanta. I got on my 1 p.m. flight, got home and took a nap and said I would go to the office later. While I was taking a nap my neighbor rang my doorbell and said, ‘I really have some bad news, Dr. King has been shot.' ”

Cotton knew of the dangers but believed in the civil rights movement. It's why she left Virginia and followed her pastor, Rev. Wyatt T. Walker, who was head of the NAACP and the Congress of Racial Equality, to help King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Atlanta.

"I became director of education for SCLC," Cotton said. "And my role was to plan the five-day sessions to help black folks un-brainwash themselves."

How King influenced her: "After his death, I worked with Mrs. King to start the King Center ... Now I spend a lot of my time speaking and teaching about Dr. King and the civil rights movement. I do a lot of work looking at the lessons we learned and helping people organize. People are doing a lot of creative things, building off of the civil rights struggle. I am also finishing my book, 'If Your Back's Not Bent: The Movement from Victim to Victory,' which will be out soon. And I am always answering the question of Dr. King's last book, 'Where Do We Go from Here?' "

Editor's update: Dorothy Cotton died in 2018. She was 88

Lawrence Edward Carter Sr., 70, Atlanta

Dean of the Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel at Morehouse College

As a high school student in the 1950s, Carter dreamed of attending Morehouse College, but couldn’t afford the tuition. In 1979, he finally got there.

Carter met King four times, first as a 10th grader in Columbus, Ohio when King visited his church.

"He asked my name and asked if I had considered [attending] Morehouse," Carter said.

Carter would hear King speak again at a local high school.

"I was swept off my feet and rushed back to the school to call my mother to tell her I wanted to go to Morehouse," Carter said. "But she was working three or four jobs and we couldn’t afford it. So I decided that I would go to Boston University and be taught by the same professors who taught him."

Carter met King again when he was a student at Boston University, which he said pleased King. He recalls the heartbreak of hearing of King's death.

"With tears streaming down my face I prayed out loud for the Lord to let me do something significant for Martin Luther King Jr., before I close my eyes," Carter said. "[Former Morehouse President] Hugh Gloster invited me to be dean of Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel on July 1. 1979."

How King influenced him: "Dr. King helped me prepare my vision for my ministry and for all of my peace work. Martin Luther King Jr. is a moral cosmopolitan. His most famous statement is proof of that -- 'Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.'

"He did not believe in putting a straightjacket around his expression of unconditional love of Christ. There was an internal consistency about what he believed and sought. That is how he impacted me. (Having not attended Morehouse as an undergraduate) King would say to me that what I am doing is a much more powerful response to his recruitment. He did not realize he was anointing me to keep his message alive. I have kept his Kingian, non-violent philosophy alive in the academy. I have been here for 33 years. I have spoken in 37 countries about him. He would be proud."