Remembering Camille O’Brien, Emory nurse who served in World War I

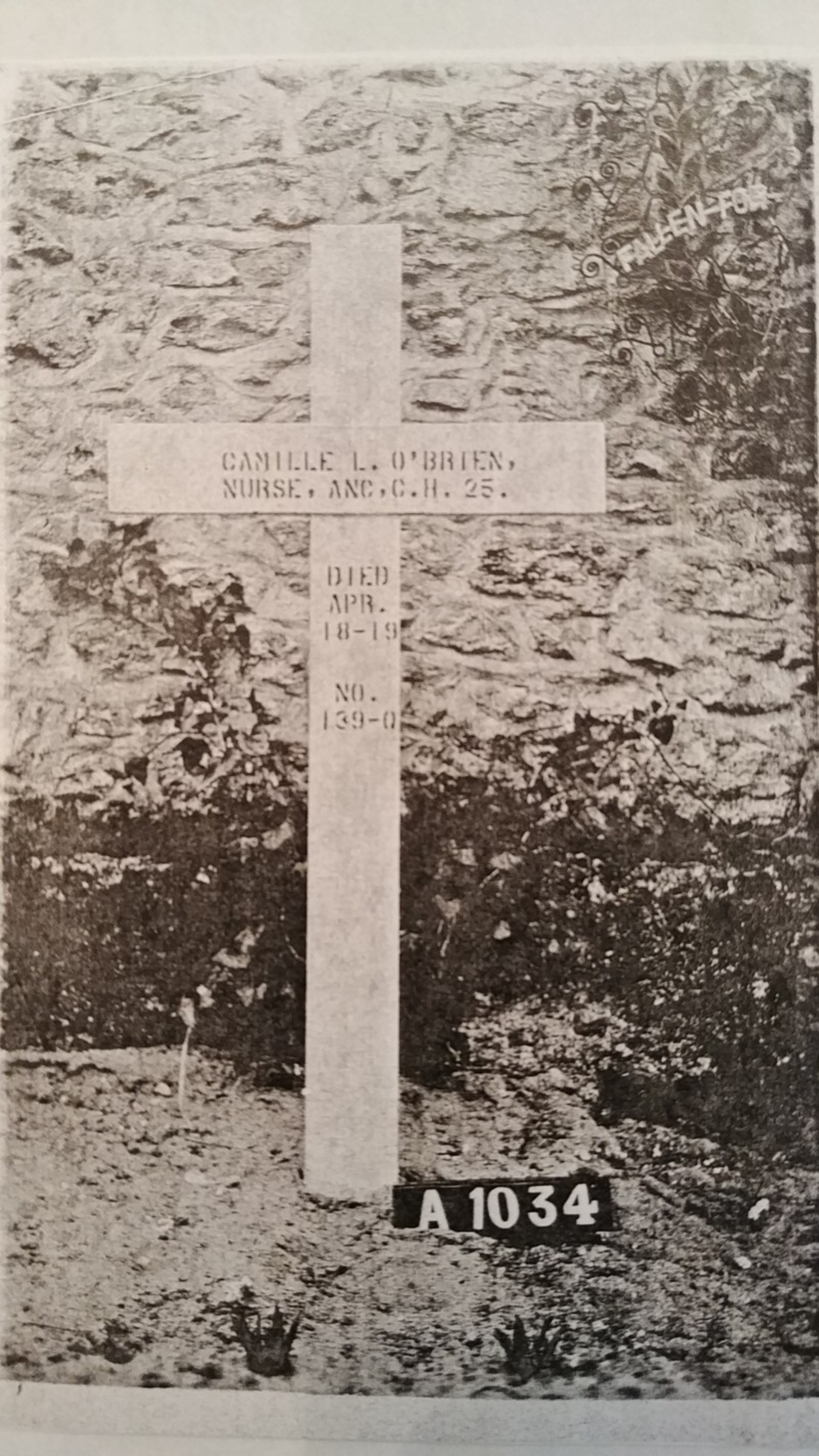

Until recently, everything 84-year-old Roswell resident William Cawthon knew about his great-aunt he learned from a suitcase in his grandmother’s attic. In the old trunk, the U.S. Navy veteran recalled a collection of Camille Louise O’Brien’s personal effects, including a nurse’s uniform, some World War I helmets, artillery shells from the battlefield and a posthumous letter from the chief nurse of Emory’s World War I unit with a photo of O’Brien’s original gravesite — in France.

Now, thanks to the relentless curiosity of Roswell cop-turned-local historian Michael Hitt, O’Brien’s phenomenal story, once a piece of nearly forgotten history, is finally getting the recognition it deserves.

Born in Barnett, Georgia, O’Brien was a member of the Emory WWI nursing unit and was the only Red Cross nurse from Atlanta to die in France during the war effort.

Before joining the Emory unit, O’Brien attended the University of Georgia’s women’s campus and worked at the St. Joseph’s Infirmary.

In 1918, she reported north of Atlanta to Camp Gordon for training along with approximately 100 other nurses before departing for Europe. Along the way, Hitt said, O’Brien and her colleagues witnessed three horrific U-boat attacks, including one surfacing behind their own troopship on July 29, 1918.

Stationed at Base Hospital 43 in Blois, France, O’Brien was assigned to the largest of seven Emory unit buildings and often worked 14-hour shifts under the unit’s chief surgeon.

The Emory chaplain, 1st Lt. Jackson Allgood, often recalled an admonished O’Brien making the rounds despite looking quite ill herself.

“I cannot rest while more men are being brought in than we can dress,” she’d say to concerned colleagues, according to Hitt.

When the war ended in November 1918, O’Brien spent her free time collecting French and German artillery shell casings at the Verdun battlefield.

“It’s as if she wanted to understand where these men came from, the horrors they must have witnessed,” Hitt said.

In January 1919, O’Brien’s Emory unit was told to make its way back to the United States, but she and a handful of others chose to stay behind to continue serving the countless wounded soldiers in need of medical care.

Months later, according to Hitt, O’Brien began complaining of headaches amid the great Spanish influenza pandemic.

On April 18, 1919, after contracting spinal meningitis, she died from infection. Even on her deathbed, chief nurse Caroline Dantzler recalled, O’Brien scoffed at the idea of having a doctor tend to her rather than focus on the ill soldiers.

O'Brien was buried with full military honors alongside soldiers in Blois. She was only 35, according to Atlanta Constitution archives.

“You her people, may keenly feel hurt that she’s buried among strangers, but the ravages of this war have created a bond that you cannot explain,” Dantzler wrote in a letter to O’Brien’s sister following her death. “You do not know what it’s like for us to give her up.”

To honor the late O’Brien’s dedicated service, Hitt — through his work with the World War One Centennial Commission — contacted the French Embassy in 2016 to ask if they’d be interested in holding a memorial service at her grave. But embassy members were perplexed. They informed Hitt the body had been brought back to Atlanta aboard the USAT troopship St. Mihiel in December 1921, just two years after O’Brien’s death. She was buried without a marker at Greenwood Cemetery, less than an hour from her great-nephew.

“I was really flabbergasted,” said Cawthon, wondering why his grandmother never mentioned her sister to anyone in the family, “but it gave me a little closure, learning she was in Atlanta.”

Last month, nearly 100 locals came out to Atlanta’s Greenwood Cemetery for a remembrance ceremony in honor of O’Brien, 100 years after her death.

“She was left in an unmarked grave, so we are here to finish what was left undone,” Hitt, who organized the memorial, said. “This ceremony gives her current family the opportunity to say a proper goodbye, while marking her grave with a special headstone.”

Together, Cawthon, Hitt, local Red Cross volunteer nurses and others gathered to unveil a new marker for O’Brien’s resting place paid in full by the local funeral home H.M Patterson & Son.

Former Emory chaplain Woody Spackman officiated the service, a nod to O’Brien’s 1921 funeral officiated by Emory chaplain Allgood.

In addition to her gravesite at Greenwood Cemetery, the beloved nurse’s name and military service number can be found on the 1920 Pershing Point Plaza plaque from the War Mothers’ Service Star Legion, a group of mothers, sisters and wives of servicemen. O’Brien is the only woman among WWI soldiers from Atlanta honored.

Her personal effects — the artillery shells, nurse Dantzler’s letter and more — have been given to the Atlanta History Center for a future display in her honor, said Cawthon. This Memorial Day, he’ll attend a Smyrna service where Hitt will continue to share O’Brien’s inspiring story.

“She was a hero if you really get down to it,” said Cawthon. “I’m still in a state of shock.”