Published Jan. 1, 2012

Guards found the dead tomcat last summer, lying between two fences that separate inmates at Phillips State Prison in Buford from the outside world.

Curiously, the cat's belly had been stitched together, so suspicious prison officials took a closer look. Inside the animal, they found eight cellphones. Someone had tried to toss the dead feline over both fences, but the throw fell short.

At Hancock State Prison, a basketball filled with 50 cellphones was rolled through a hole in a perimeter fence. A guard at the same prison allegedly tried to smuggle in a phone wrapped in aluminum foil, disguised as a baked potato.

Georgia prison officials say cellphone smuggling is the most pressing problem they face. Cellphones are such a hot commodity inside the walls they're being confiscated by the thousands.

And officials say the phones are a menace, wreaking havoc inside and outside the cell blocks. Phones are used to coordinate attacks inside the prison walls and are enabling inmates to continue criminal activity outside of prison. They've been used to threaten witnesses and coordinate simultaneous protests at multiple prisons.

"They present a clear and present threat, not only to the inmates themselves but to our staff and to the public, " Corrections Commissioner Brian Owens said. "They're not about calling mom on Thanksgiving. They're for power, money and gangs. It's a big business and a tremendous problem."

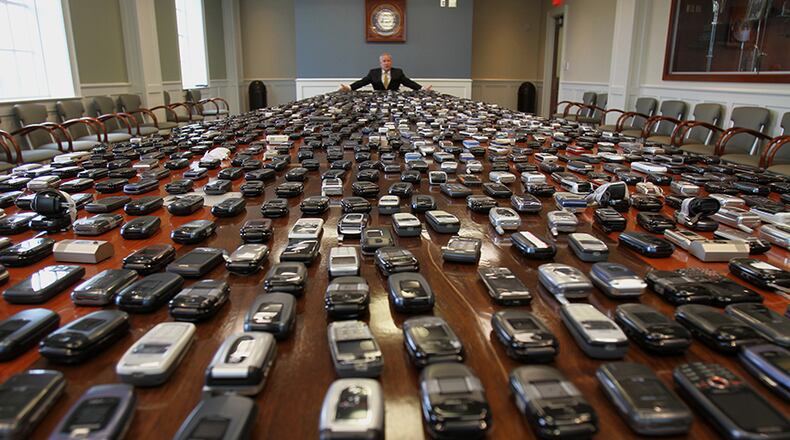

Over a one-year period ending in July, corrections officials confiscated more than 8,700 illegal cellphones, Owens said. "And if we've confiscated 8,700 cellphones, the question I have is how many have we not been able to seize?"

Behind bars, the cellphones, mostly prepaid, cost $200 to $600 each.

Owens said a jamming device that blocks cellphone signals would allow prison systems to combat the problem. But the Federal Communications Commission has not allowed states to use it, despite a report from the National Institute of Justice that indicates cellphone use is a problem at prisons across the country:

*In Texas, a death row inmate who killed four people used a cellphone to threaten a state senator, prompting a lockdown of the entire prison system.

*In Nevada, a prison dental assistant was convicted of helping an inmate get a cellphone to plan a successful escape.

*In South Carolina, a captain in charge of intercepting prison contraband was shot six times in the chest at his home after an inmate used a cellphone to call an ex-con to carry out the hit.

Even the most dangerous inmates --- those who are the most closely monitored --- have been caught with cellphones.

While Fulton County courthouse killer Brian Nichols awaited trial in jail, someone smuggled phones to him on two occasions. Nichols, who was later convicted of killing a judge, a deputy and another man in the courthouse rampage, used the phones to plot an escape and send lewd photos of himself to his pen-pal girlfriend.

Last year, California prison officials found a cellphone on notorious mass murderer Charles Manson --- the second one found on him in two years.

In Georgia, it is a felony to smuggle a cellphone into prison, with a maximum punishment of five years behind bars. The prison system asks the state Board of Pardons and Paroles to extend sentences by six months for all inmates caught with cellphones.

But the smuggling hasn't landed only inmates in hot water. Last year, 312 civilians and 59 prison staff members were charged with trying to smuggle contraband inside state prisons, and most cases involved cellphones, Owens said.

Owens, who has overseen the system since 2009, says he has an easy answer when asked what his biggest problem is.

"It's not our budget, not staffing, not infrastructure, not overcrowding, " he said. "It's cellphones."

Before cellphones, inmates could only use prison pay phones, and officials decided who inmates could call, when they could call and how much time they could spend on the phone. The calls were recorded. But inmates say cellphones are much less costly than the expensive collect calls paid for by their families.

On Nov. 28, Gov. Nathan Deal wrote the FCC, asking it to reconsider its position on the use of jamming devices to disrupt cellphone calls in prisons. Deal noted that two recent disturbances at state prisons "only continue to underscore the nationwide epidemic of illegal cellphone usage in prison facilities across the United States."

The incidents --- one at Telfair State Prison, the other at Hancock State Prison --- left 15 inmates hospitalized and a guard with a leg injury, Deal wrote. Illegal cellphones were found to be the catalysts behind the two fights, the governor wrote.

Deal said prison officials have investigated a number of technologies to fight cellphone use in prison and are convinced that cellphone "jammers" are the most cost-efficient and timely response.

"Carving out an exception for the use of this technology in prison facilities is sound policy to protect inmates, corrections employees and the public, " he wrote.

The FCC shares Deal's concerns and is working with prison authorities and others to address the matter, a commission spokesman said. There are concerns, however, that the technology poses a risk of interfering with legal calls outside the prison grounds, including calls to public safety, the spokesman said.

Other states use dogs to sniff out illegal cellphones. At least two states have used a technology that, instead of jamming calls, prevents calls from reaching their destination. But Owens said those methods are too costly. He estimated that "managed access" technology would cost the prison system millions of dollars. Using dogs to find cellphones also would end up being too expensive, he said, because he would have to hire and train dozens of new corrections officers.

Tod Burke, a criminal justice professor at Radford University in Virginia who has studied the issue, said there are legitimate concerns that jamming devices could disable phones used by law enforcement.

"If I'm driving by as a police officer, I'd be concerned whether a jamming device inside a prison is going to jam my own frequency, " Burke said. "But the technology is advancing and can probably be isolated enough so that it's not going to interfere with phones outside the prison setting. And in rural areas, where many prisons are located, who are you going to interfere with anyway?"

District Attorney Fred Bright said cellphone smuggling is a big problem in his sprawling eight-county circuit, which includes a number of Middle Georgia and east Georgia prisons.

His office prosecutes 40 to 50 cases a year involving inmates, prison workers and visitors, he said. This included an indictment against a guard caught trying to sneak in a cellphone he'd stuffed inside a fish sandwich, Bright said.

The GBI is investigating a cellphone smuggling case at a unspecified prison in Middle Georgia, said the agency's director, Vernon Keenan. It began as a drug smuggling case but has broadened in scope, he said.

Keenan added that the GBI is often called in when there are assaults inside the prison system and during those investigations agents have learned that cellphones were involved in coordinating the attacks.

One prison inmate recently killed a fellow inmate during an argument over a cellphone, Owens said, declining to give more details because the investigation is ongoing.

Federal prosecutors in Atlanta recently convicted Carlos Garcia for using a cellphone smuggled to him inside Valdosta State Prison to transfer $250 from a 93-year-old woman's credit union account to his inmate account.

The 36-year-old inmate had obtained the victim's credit union account numbers and PIN number from an accomplice, who had stolen the woman's wallet while she was shopping in Conyers.

At the time, Garcia was serving a 10-year term for identity theft and fraud convictions in DeKalb County. After transferring the money to his prison account, he tried to steal again from the elderly victim, who had $120,000 in the bank, prosecutors said.

Garcia used his cellphone to make online purchases. But, by that time, law enforcement officials were already onto the scheme and blocked the transactions.

Prosecutors said the inmate was charged with bank fraud and aggravated identity theft after he called the credit union to find out why the charges were not going through.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured