Pellom McDaniels III didn’t sleep much.

Wasting time, he'd say.

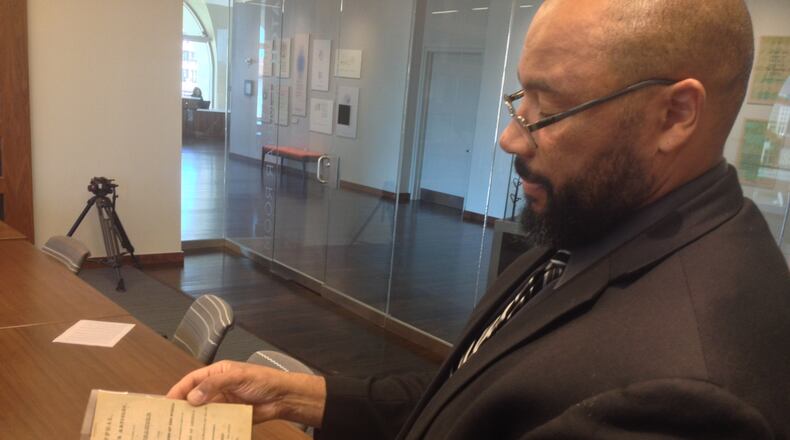

Instead, he thrived on learning and teaching others, particularly about African-American history and culture.

“He had a lecture at the ready,” said his wife, Navvab McDaniels. “Anytime you wanted to talk about something, he knew about it … I’m standing in his office now and there are thousands of books. He lived every ounce of life that was given him. He lived a life for three different people.”

McDaniels, the curator of African American Collections at Emory University’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, died Sunday at age 52.

The father of two and his wife would have celebrated their 24th anniversary next month.

Navvab McDaniels said her husband had health issues, but doctors think his death was the result of a “neurological event.”

A graveside service will be held later this week.

A member of the Baha’i faith, McDaniels embraced a broad view of the world.

“There’s a teaching in the Baha’i faith that service is the highest form of worship and he believed that,” said Navvab McDaniels.

Randall K . Burkett, retired curator of African American Collections at Emory, met McDaniels through the late Professor Rudolph Byrd, who urged him to hire his doctoral student for a project in special collections.

It was a “nasty” task, recalled Burkett.

The school had acquired the Carter G. Woodson library, but it came covered with a thin film of oil, the result of a furnace back-up in the old Washington, D.C. headquarters of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

Related: Sign the guestbook for Pellom McDaniels III

McDaniels and another graduate student had the unenviable job of carefully cleaning each book. Halfway through that work McDaniels showed Burkett his fingertips which had become raw from contact with the oil.

“Pellom was a giant of a man: not only in stature but in talent, in intellect, and in energy,” Burkett said in a statement. ” He built the collections in important new ways but also was responsible for extending their reach to the community through programs and exhibitions.”

McDaniels was named the associate curator in 2012, then took over as curator when Burkett retired in 2018.

More: Emory opens SCLC/Women's collection to the public

McDaniels was a noted expert on African Americans in sports, a professor, artist and former professional defensive football player who played for the Birmingham Fire, the Kansas City Chiefs and the Atlanta Falcons. He wrote several books including “The Prince of Jockeys: The Life of Isaac Burns Murphy,” who was the first jockey to win the Kentucky Derby three times.

An avid gardener, McDaniels doted on his two children, Ellington “Duke” McDaniels, 18; and Sofia McDaniels, 15.

He loved the process of taking things from a seed to a plant,” said Navvab McDaniels. That was whether it was a plant or a student. “He marveled at this process.”

McDaniels was born in San Jose, California and raised by his grandparents, who were both factory workers.

As Navvab McDaniels tells the story, he was a gifted child and self-sufficient. When it was time for high school, McDaniels was worried about going to the school district in the neighborhood, which didn’t have a good reputation.

Instead he used the address of an uncle who lived in a better district.

“He got up every day at 5 a.m. and took the city bus to a different school,” she said. There, he came to the attention of the football coach, who encouraged him to try out for the team.

He attended Oregon State University on a football scholarship and later played professional football before retiring.

Will Shields, a retired NFL guard met McDaniels when the two joined the roster of the Kansas City Chiefs and became fast friends.

“We were just two guys trying to figure out where we were going, how to get to the next level and stay there,” Shields said in a telephone interview. “He was always the guy who talked about the next step. He knew the sky was the limit.”

In 2015, McDaniels was honored with the NCAA’s Silver Anniversary Award, which recognizes distinguished former student-athletes on the 25th anniversary of the end of their intercollegiate athletics eligibility.

In an interview on the NFL Players Association website, McDaniels said he had three goals when he grew up. “I wanted to be a professional football player, I wanted to be a prolific discus thrower and I wanted to be a college professor. Education has always been a part of who I’ve been while I was developing.”

When he retired from professional football, McDaniels turned to academia.

He earned both his master of arts and doctorate degrees in American Studies from Emory and served as an assistant professor in history at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, before returning to Atlanta.

Clinton Fluker, assistant director of engagement and scholarship at the Atlanta University Center’s Robert W. Woodruff Library, worked with McDaniels at Emory.

He remembers his mentor saying, “It was our duty to share the very rich history of African Americans with the world. He felt history was important for identity, so our stories aren’t lost. That’s why he so rigorously searched for those stories and shared them with the public.”

Longtime Atlanta resident Imara Canady met McDaniels when he came to visit his future wife in Atlanta.

“He was one of those brothers who defied every stereotype that some people have of professional athletes,” said Canady. “He was really just a holistic kind of brother. He really made you feel safe to explore new opportunities.”

Noted artist Fahamu Pecou is a former student and friend.

He said McDaniels often supported young artists and once traveled to Paris when Pecou had a show.

When he was a student, Pecou remembers the two walking laps around the quad discussing books, ideas, black history and art, culture and philosophy.

“Pellom was a walking library,” he said.

Nsenga Burton, a professor in Emory’s film and media studies program, worked with McDaniels on several projects.

As recently as last week the two were emailing each other and talking on the phone about a project on the anniversary of the 19th amendment, which gave women the right to vote. The last time they talked, McDaniels was working in his garden.

Relaxed. Happy.

“Pellom is with the ancestors now, which makes complete sense because he kept so many of their voices alive through his work,” she said in a Facebook post. “Many will make sure Pellom’s voice lives.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured