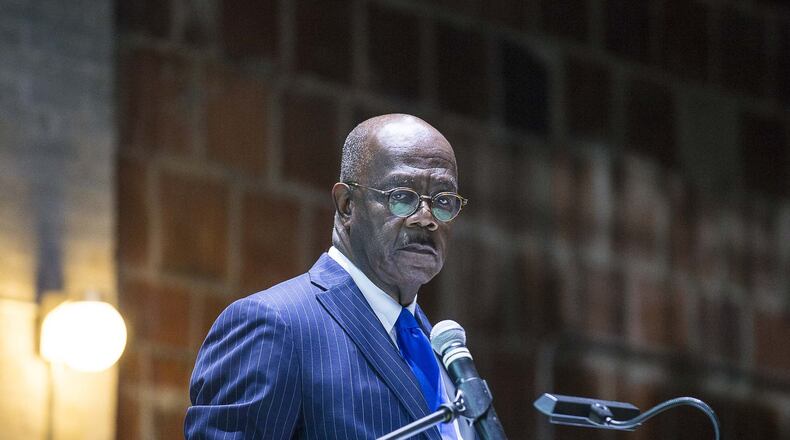

Top city of Atlanta officials appear to have overridden financial controls and bypassed the City Council to funnel $250,000 to Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard, who then used a large portion of the money to supplement his own salary, according to documents obtained by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Channel 2 Action News.

Invoices for two $125,000 payments, which occurred during Mayor Kasim Reed’s administration, say the checks were for the district attorney’s office, the documents show. The AJC and Channel 2 previously reported the money actually went to a nonprofit organization controlled by Howard.

Atlanta Police Chief Erika Shields, whose name appears on one of the invoices, defended her role but this week expressed frustration with the payments. At the time, Shields was the deputy chief in charge of department finances.

“Circumventing the processes that are in place with regard to expenditures of city money is not something I would be a part of, under any circumstances,” Shields said. “It is now becoming clear that this program was designed for reasons other than taking care of the community and I regret that the police department was complicit — albeit unknowingly — in its funding.”

George Turner, who was police chief at the time of the payments, said the request came from “the mayor’s office.”

“I assumed all policies and city council approvals were in place,” Turner wrote in a statement Wednesday. “After the funds left the City, I had no further information about its intended use.”

City officials say that the payments required Atlanta City Council approval, but no one can find legislation authorizing them.

County officials say they can’t find any evidence of the money being deposited into a county bank account. Financial documents show the money went to Howard’s non-profit.

The city issued the two checks to “FULTON COUNTY DIST ATTY OFFICE” in 2014 and 2016, which Howard personally endorsed and deposited into a Bank of America account, according to documents obtained through the Georgia Open Records Act.

Accounting records from Howard’s nonprofit show a $125,000 deposit dated the same day he endorsed the 2014 check.

Howard has said he retained personal control over some of the funds, with the city’s blessing, to increase his take home pay. Tax filings and internal records of the nonprofit, People Partnering for Progress, show that Howard used the payments to supplement his salary by at least $170,000 from 2014 to 2017. The nonprofit says its mission is to reduce gang violence.

The highly unusual arrangement has prompted a criminal investigation by the GBI at the request of Attorney General Chris Carr and resulted in Howard being accused of a dozen violations by the state ethics commission.

Howard declined to answer a question from the AJC about why he would have invoiced the city in name of his office if the money went to his non-profit. But he has strongly denied all allegations of impropriety, and previously said he expects to be exonerated “if the facts are followed.”

Howard also said the timing of the investigations, coming weeks before the June 9 primary where he faces opposition, “is not lost on me.”

“This is not the first time what would be considered as an administrative matter for other Georgia elected officials is turned over to the GBI for investigation when it involves the Fulton County District Attorney,” Howard said in a statement.

‘Somehow they found a way’

Atlanta City Council President Felicia Moore said she can find no legislation that approved the payments, after extensive searches of city council meeting agendas dating back to that time frame.

“It should not of happened in the first place,” Moore said. “Our charter and code lays out the council is the only body that approves expenditures. This has been done outside of what the legal authority would have been, if that is the case.”

Then, referring to Howard and Reed, Moore said: “It sounds to me that there was some agreement between him and the mayor, and somehow they found a way to fund the money.”

Reed did not respond to multiple messages seeking comment for this story.

Michael Smith, a spokesman for Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, said: “While the transactions in question predate this administration, we are in the process of examining the facts surrounding the matter.” Bottoms was on the City Council at the time, but said Wednesday that she had no knowledge of the payments.

When asked about the payments, Howard provided a letter he sent Reed in May 2014 in which he said he was underpaid for the position. Howard asked the city to give him an annual supplement of $81,259. (Howard was making $158,241 that year; he now makes roughly $175,000.)

Howard said Reed agreed, so long as it was tied to services for the city, particularly addressing repeat offenders and expanding the DA’s community prosecution program. Recidivism is among the city’s most urgent problems and the county jail is persistently overcrowded.

Checks for $125,000 were issued in 2014 and 2016.

Howard has said the money was used for two purposes: “First, to enhance the community prosecution program and, secondly, to fund my requested salary supplement.”

Former City Council President Ceasar Mitchell told the AJC that Howard approached him in 2014 requesting the supplemental salary, and that he told Howard the council was unlikely to approve the request because he wasn’t a city employee.

“He wasn’t trying to hide the ball,” Mitchell said.

Mitchell said that he suggested Howard put together a proposal highlighting and expanding the work of the DA’s community prosecution program, and ask the city to fund it. Mitchell recalled saying a larger program could provide justification for a salary increase.

But they never discussed Howard paying himself through his non-profit, Mitchell said.

‘Everything was done under duress’

Records turned over to the AJC and Channel 2 show that an Aug. 6, 2014, invoice for the first check indicates it was signed by Tracy Woodard, then the business manager for the Atlanta Police Department. In an interview, Woodard said her signature was forged on one of the documents.

But Woodard said she did sign another form because she was ordered to do so by then-deputy chief Shields, and feared she might lose her job if she didn’t comply.

“Everything was done under duress,” Woodard said.

Woodard said the payments to Howard’s office were not budgeted and that city officials overrode financial controls.

“That was something that the mayor’s office took from us (APD),” Woodard said. “I fought against it.”

Shields said she believed the payments had been properly vetted.

Woodard later unsuccessfully sued the city for wrongful termination, alleging she was dismissed after objecting to some purchases, including expensive SUVs for the mayor’s office. Her departure was not related to the Howard payments.

The Open Records Act request also yielded an Aug. 6, 2014, letter Howard wrote to the mayor’s office in which he said it was his understanding “the funding has been approved.”

Howard suggested the funding be set up this way: “Community Prosecution Staffing $60,000; Community Prosecution Support (mileage/travel expenses) $45,000; and Program Costs (defray CP office rental costs, office supplies, printing) $20,000.”

The letter made no mention of money being used to supplement Howard’s salary.

The nonprofit’s internal records show it paid Howard $30,000 over the rest of that year, in six $5,000 increments. Tax filings with the IRS show the nonprofit paid Howard an additional $50,000 in 2015 and another $20,000 in 2016.

In September 2016, the DA’s office returned to the city asking for another $125,000 for the community prosecution program.

This time Howard provided no detailed description of the services the DA’s office would provide, according to records the city provided. After the payment was approved, the nonprofit paid Howard another $70,000 in 2017, tax filings show.

The form that authorized the check appears to bear the signature of John Gaffney, the city’s current deputy chief financial officer. The city declined to make Gaffney available for an interview, or explain why he approved the payment.

The words “FORCE APPROVE” appear at the top of the form — a notation that apparently forces payment through the city’s accounting system without the standard approvals.

City Auditor Amanda Noble said a “FORCE APPROVE” is often used in case of emergencies, and that another notation on the form is “also consistent with needing a payment quickly.”

It is rarely used, she said.

“I haven’t seen that before,” Noble said.

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured