How ‘Atlanta Compromise’ divided black America and cemented Washington’s legacy

On a quiet corner in Piedmont Park, near 14th Street where joggers and soccer moms stroll past with no clue, one of the most controversial speeches in American history was delivered.

It was Booker T. Washington’s Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition speech of Sept. 18, 1895, where he delivered a clear message that the sons and daughters of former slaves should not challenge segregation.

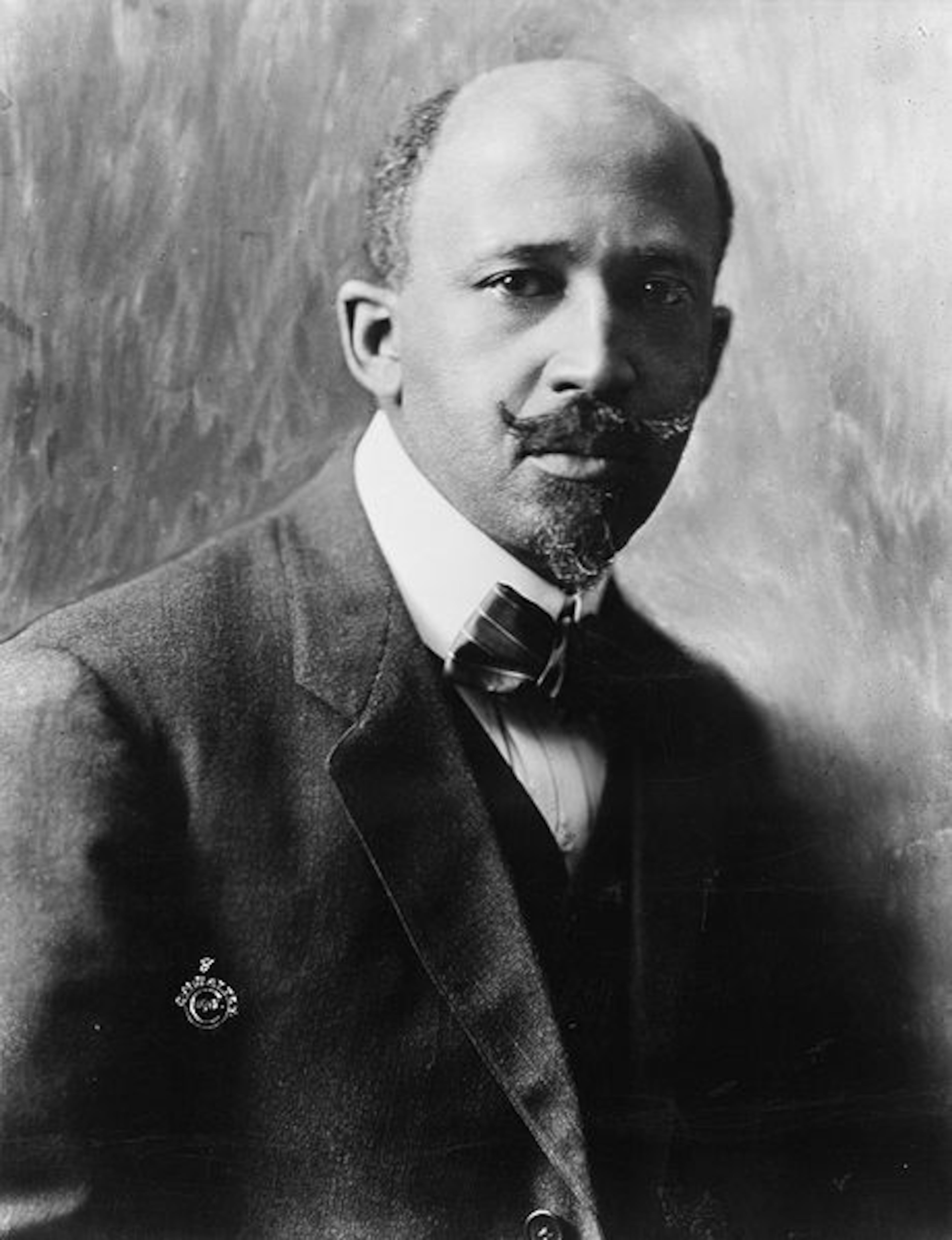

It is unclear if Washington ever actually named the speech, but his political and academic rival, W.E.B. Du Bois called it, the "Atlanta Compromise," believing that African-Americans should engage in a struggle for civil rights.

Born a slave in 1856 on a plantation in southwest Virginia, by 1895, Booker T. Washington has risen to become the most powerful, and in some regards, respected black man in the country. Most significantly, he was president of the Tuskegee Institute, which he had established 14 years earlier in 1881.

His appearance to represent black America at the Atlanta Exposition seemed natural.

Washington, who wore his light-skin as the result of his white father whom he never knew, rose to the wooden stage and delivered a rousing speech to a mostly white audience.

Using that platform, he refused to challenge segregation. Instead, he urged blacks to "Cast down your buckets where you are" and make progress as agricultural and industrial laborers.

He told the crowd that Southern blacks would work quietly and submit to white political and legal rule in exchange for a guarantee that blacks would receive a basic education and due process in the law.

In addition, those same blacks would not agitate for equality, integration or justice.

“The wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly, and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be the result of severe and constant struggle rather than of artificial forcing,” Washington said.

He went further by saying that blacks would do well to take advantage of the knowledge of labor – some of which he was teaching at Tuskegee – rather than in their limited knowledge of the arts.

“No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem,” Washington said. “It is at the bottom of life we must begin, and not at the top. Nor should we permit our grievances to overshadow our opportunities.”

Southern whites loved the speech. Black intellectuals hated it.

In 1903, in his classic book of essays "The Souls of Black Folk," Du Bois, who was teaching at Atlanta University at the time, offered the most stinging rebut of Washington's belief of racial accommodation and gradualism in his essay "Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others."

"To gain the sympathy and cooperation of the various elements comprising the white South was Mr. Washington's first task; and this, at the time Tuskegee was founded, seemed, for a black man, well-nigh impossible," Du Bois wrote.

Du Bois went on to write that by the time of the 1895 speech, Washington had figured out a way to appease whites, by disarming any immediate threat of segregation. Du Bois attacked Washington, by drawing on another line in the speech: "In all things that are purely social, we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress."

“This ‘Atlanta Compromise’ is by all odds the most notable thing in Mr. Washington’s career. The South interpreted it in different ways: the radicals received it as a complete surrender of the demand for civil and political equality; the conservatives, as a generously conceived working basis for mutual understanding,” Du Bois said. “So both approved it, and today its author is certainly the most distinguished Southerner since Jefferson Davis, and the one with the largest personal following.”

Du Bois would later blame the 1906 Atlanta Race Riots, which occurred a few miles south of Piedmont Park on Washington’s speech.

Washington died in 1915 and the policies he promoted in his 1895 speech soon fell out of favor. But what is now Tuskegee University, remains one of the leading black colleges in America.