House blocks ethics switch

Two hours remained in the 2012 legislative session when Sen. John Bulloch strode to the well to ask colleagues to support a bill that would protect the identities of applicants for hunting or fishing licenses.

What Bulloch didn’t say was that a committee of three senators and three House members had just reshaped the bill to enable the state ethics commission to seal records of some cases against politicians from the public.

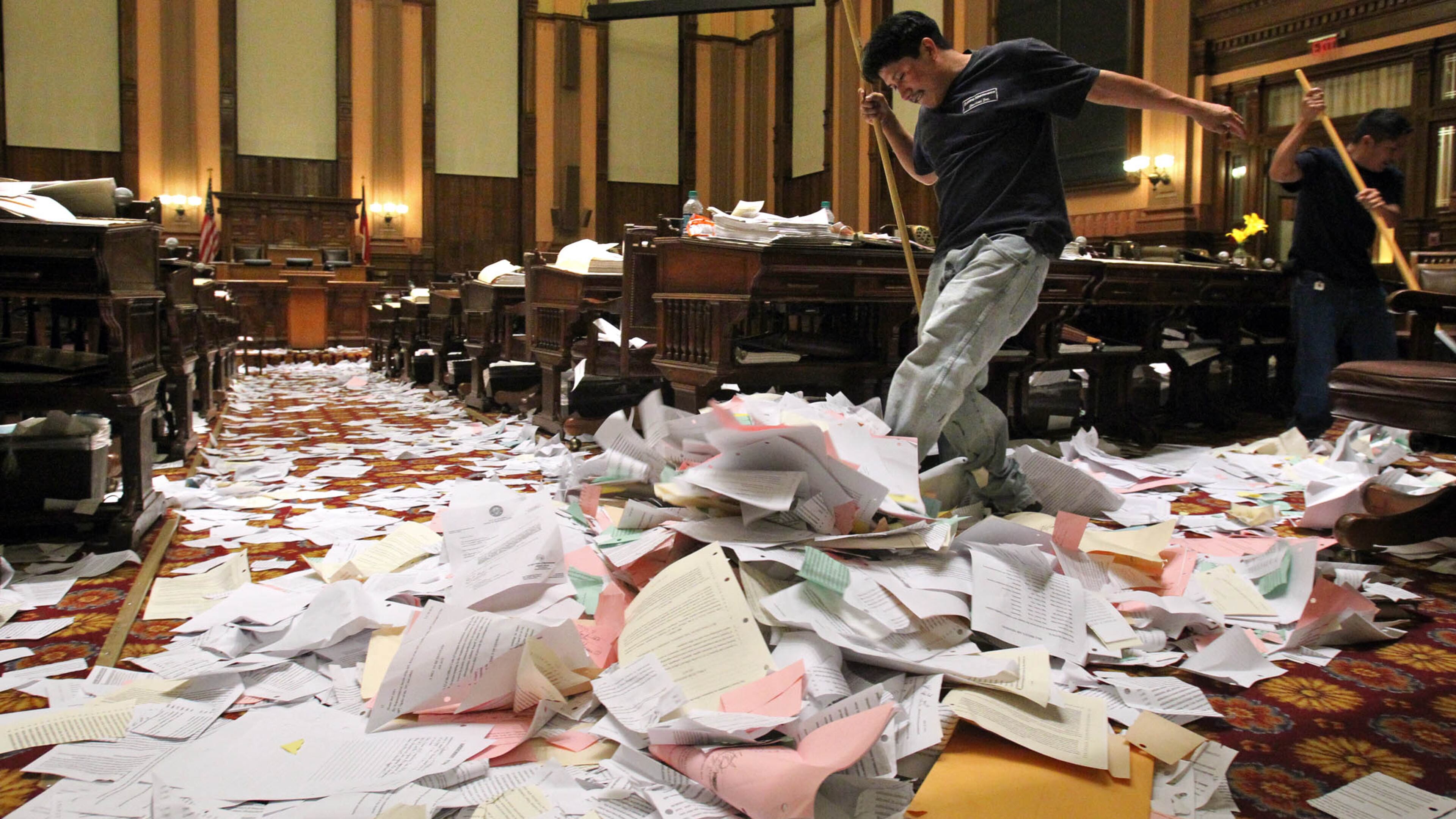

With dozens of staffers, family members and friends crowding the Senate floor — many of them talking loudly enough to drown out the proceedings — and lawmakers barely paying attention, Bulloch’s explanation went by without comment or question. At 10:02 p.m. Thursday, the Senate voted 48-4 for HB 875.

An hour later, however, when it was time for the House to vote in the dying minutes of the session, the bill met a much colder reception.

Within minutes of the Senate vote, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution had posted what happened on Twitter and Facebook; good-government lobbyists in the hall figured out what was going on; political bloggers picked up on it.

“I know that anything can be tried and anything can happen at 11 p.m. on Day 40 [of the session], but I still found this an amazingly bad idea,” said Rep. Mary Margaret Oliver, D-Decatur, who led the opposition after she learned what had been added to the bill.

HB 875 went down in flames, 25-143, despite the support of House Ethics Chairman Joe Wilkinson, R-Sandy Springs.

Wilkinson called opposition to the bill “disgraceful” and argued that people who are innocent should be protected from scrutiny, he said.

“Why should [a politician’s] name be up there if he didn’t do anything wrong?” he said.

House Speaker David Ralston, R-Blue Ridge, didn’t take a position on the bill.

But he said, “I knew the House would take a hard look at it. I was pleased that they did. I always expect the House to vet these bills carefully.

“I don’t [know where it came from]. They make me aware of those things when they come out, but when I’m dealing with a dozen or more conference reports, I’m not always aware of everything that’s in them.”

The last-minute ethics changes came 10 days after national groups put out a report ranking Georgia’s public corruption and government openness laws the worst in the nation.

State officials dismissed the report as biased. But legislative leaders have also ignored legislation put together by a coalition of advocates and lawmakers to tighten ethics laws, including putting a cap on lobbyists’ gifts. Ralston in particular has opposed a gift ban and said transparency — letting the public see what gifts politicians receive — is better than limits.

House Bill 875 started out as an uncontroversial bill for hunters and fishermen. Once it got into the House-Senate a conference committee, it became a vehicle to enable the state Government Transparency and Campaign Finance Commission to seal the records of cases in which politicians were either found not to have violated state ethics laws or had committed only technical violations. In essence, the commission could keep the public from seeing the evidence that led to the panel’s decision.

The measure also required the commission to withhold filing violations for at least 30 days and allowed it to set rules and regulations to waive late-filing fees for politicians and lobbyists.

Some lawmakers voted without fully understanding what was in the final bill.

Once he realized the ethics provisions had been added, Sen. David Shafer, R-Duluth, moved to have his vote officially changed. He had originally voted for House Bill 875.

“As a general matter, I believe public records should be available for public inspection,” Shafer said. “I did not immediately realize the full extent of the changes made by the conference committee.”

Wilkinson said the final product was a work of compromise.

The members of the conference committee were Wilkinson, David Knight, R-Griffin, and Tom McCall, R-Elberton, on the House side, and Bulloch, Don Balfour, R-Snellville, and Jeff Mullis, R-Chickamauga, on the Senate side. Wilkinson had sponsored a bill that died earlier in the session to restore rulemaking authority to the ethics commission, a privilege stripped from it by the previous House speaker, Glenn Richardson. Wilkinson saw HB 875 as a vehicle to revive his dead bill.

“I could not get the commission full rulemaking authority back, but I was able to at least get limited rulemaking authority back so they could do what has been requested by literally hundreds of local elected officials,” he said.

Wilkinson said the idea was to protect local officials who end up on the commission’s list of late filers either because of a clerical error or a “technical” violation. Wilkinson said political opponents can then use the list to hammer their opponents for having “ethics” violations.

“They said that is not fair and it’s not,” he said. “My sense of fair play is they should be given the opportunity to correct a technical defect.”

Rick Thompson, former top staffer at the commission, said some of the proposed changes were well-intentioned. In the past, he said, opponents of politicians filed frivolous complaints to get publicity. However, a 2010 law allows the commission to impose penalties for baseless complaints. Thompson, who advises Gov. Nathan Deal and other politicians on ethics laws, said some other states limit how much information they release about ethics complaints.

But he added, “A lot of times, complaints are silly and a political attack. If you close that and don’t let the public see it’s a nut-job complaint or that it has no merit, I think it could complicate things for the candidate.”

He also said reporting immediately when politicians are late to file reports, or don’t file at all, is a deterrent to those who would otherwise skirt the law.

William Perry, executive director of Common Cause Georgia, called the proposed changes “highly offensive.”

“It is again an attempt to change the ethics laws at the very last minute without vetting them, and that has caused more damage than good,” he said.

“They brag about the laws that they have put in place, but once we see them function in reality, they are not working well at all.”

Staff writer Christopher Quinn contributed to this article.