If law-abiding pilgrims went hunting for holiday grub in modern day Georgia, their Thanksgiving dinner wouldn’t include turkey.

Georgia’s woods are alive with the sound of gobbling — an estimated 250,000 of the delicious birds live here, wildlife officials say — but state regulations forbid hunting them during the time of year when people most want to put one on their table. Turkey hunting is allowed only in the early spring, meaning if you want to eat the bird in the fall, you’re going to need a really big freezer — a wild Tom can weigh over 20 pounds.

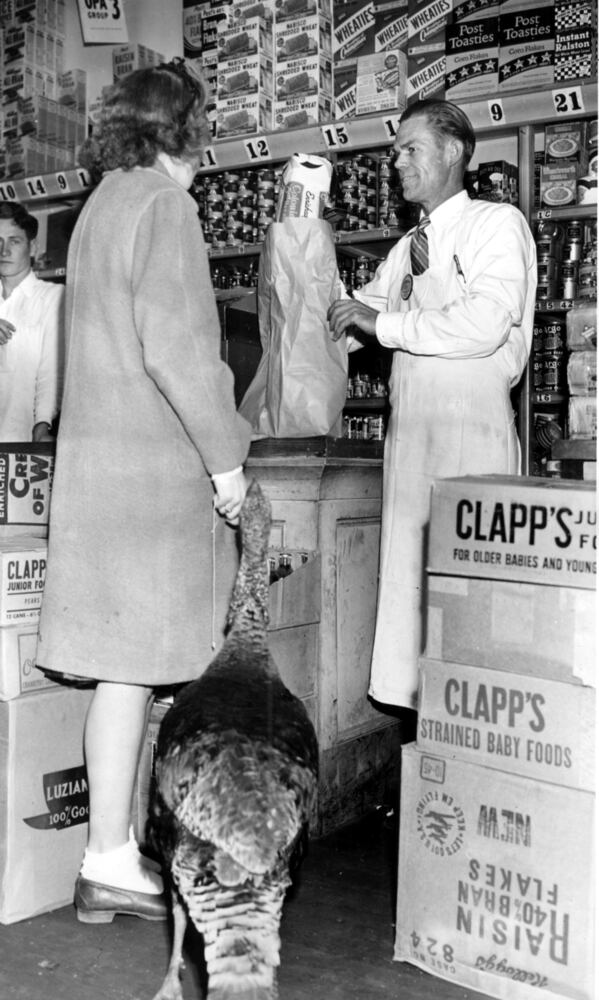

Credit: Courtesy photo/Joe Berry

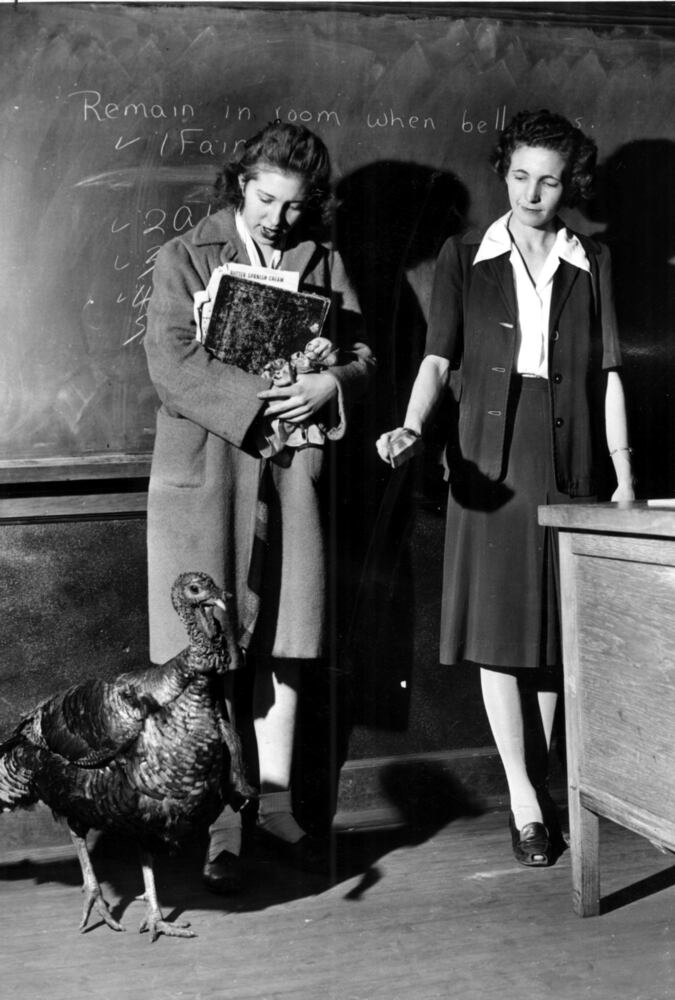

Credit: Courtesy photo/Joe Berry

What can Georgia hunters legally kill in late November? Deer, rabbit, raccoon, squirrel and ‘possum are in season, which explains why city dwellers now hunt their dinner in grocery stores. Those who prefer shooting down fowl that can truly fly can eat unlimited crow; but dove, quail, duck and geese have bag limits.

What did pilgrims actually eat for the first Thanksgiving meal in 1621? Historians aren’t sure, but an abundance of meat was definitely on the menu, said Dr. Marianne Holdzkom at Kennesaw State University. It’s believed Native Americans contributed deer meat to the celebration, but there’s evidence the pilgrims went “fowling” for their feast.

They likely downed ducks and geese, Holdzkom said, but it’s not known if they bagged a turkey, which are notoriously elusive prey despite their large size.

Turkeys are revered by hunters for their wily ways. The birds have extraordinary eyesight — they can see you blink from 50 yards away — and can remember which turkey calls and decoys are not the real deal.

Pilgrims likely would have had better luck tracking the elusive birds in snow, Holdzkom said, which would have fallen after the first feast.

The settlers settled down for the big meal in September or October instead of November, Holdzkom said. During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln set the national day of thankful feasting in late November, but “that would have been too late in the season” for a fall feast in Massachusetts, Holdzkom said.

America’s original big bird has made a strong comeback since the 1970s when the number of game birds in the state declined to about 17,000, said Emily Rushton, turkey program coordinator for Georgia’s Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Resources Division.

The turkey population has taken a bit of a dip again in recent years, said Rushton, from a high of about 350,000 critters in 2003. The reasons for the drop are not fully understood, but likely include a loss of habitat. Turkeys need trees to roost in at night, but prefer open areas to forage for food, build nests and raise offspring, Rushton said.

To increase turkey numbers, from 1973 to 1996 the state captured birds that were in unsuitable areas and moved them to prime real estate. Some birds were imported from other states.

Why is turkey season in the spring instead of closer to the annual day of overindulgence? Turkey chicks, called poults, are born after the spring hunting season and need almost a full year to adopt adult plumage that makes it easier to determine gender. In Georgia, only the male turkey can be legally hunted.

After deer, turkey is the second most popularly hunted game species in Georgia, Rushton said.

Hunter Scott Bardenwerper has been hunting turkey for 33 years and appreciates the crafty prey.

“They are super challenging,” he said. “You are calling and they are responding. You are trying to fool him into thinking you are a boss hen he can get up with, and a lot of the time you are competing against the real thing.”

Bardenwerper, who often hunts in the mountains near Helen, said turkeys often are in tall grass and the only thing you might see is their small head acting “like a periscope.” Hitting such a tiny target with a shotgun from 40-plus yards is no easy task.

“Chances are you might not see it, but it sure sees you,” Bardenwerper said. “Best thing to do is locate them roosting the day before and then try to call them (out of the trees) the next morning. You can’t move and need super good camo. … I love turkey hunting as good as anything I do.”

The rise and fall of the Georgia turkey

Before Europeans began to settle in Georgia, turkeys were very common, experts say, but hunting and loss of habitat almost drove them out of the state.

1973 - Wild turkey population dips to just 17,300 birds. Georgia DNR begins restocking program.

1984 - Population has grown to 113,000 with a huntable population in almost every Georgia county.

1996 - DNR stops restocking program.

2003 - A peak population of 350,000 birds.

2008 - An estimated 300,000 birds.

2019 - The turkey population continues to dip down to 250,000 or so.

Select November hunting season dates in Georgia (2019-2020)

Crows: Nov. 2-Feb. 28 (No limit)

Deer: Oct. 19-Jan. 12 (12 per season)

Ducks and geese: Nov. 23-Dec. 1 (1-6 per day depending on the species, 5 per day)

Opossum: Oct. 15-Feb. 29 (No limit)

Quail and rabbit: Nov. 16-Feb. 29 (12 per day)

Raccoon: Oct. 15-Feb. 29 (3 per day)

Squirrel: Aug. 15-Feb. 29 (12 per day)

Turkey: March 21-May 15 (3 per season)

About the Author

The Latest

Featured