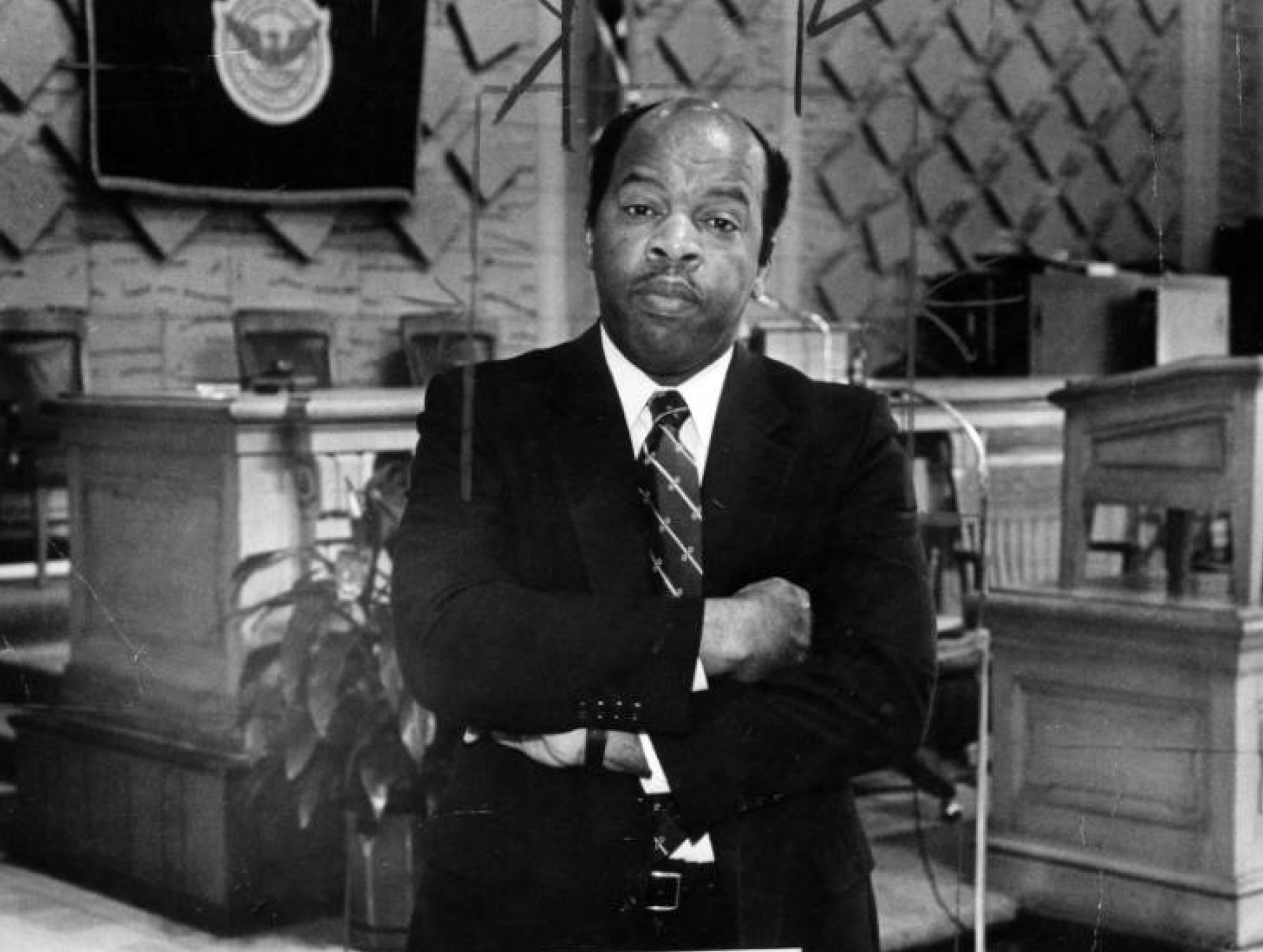

From 1982: John Lewis, butting heads with the status quo

NOTE: This article was originally published on Nov. 7, 1982, in The Atlanta Weekly magazine of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. That year, John Lewis began his political career as a new member of the Atlanta City Council. The following profile captures many of the qualities that would define Lewis as a politician into the 21st century.

Two important things happened to John Lewis in 1982. He obtained his first driver's license, and he was sworn in as a member of the Atlanta City Council. It is hard to say which event is viewed with more alarm by Atlanta's politicians. Some express doubts about whether a man who received his first driving lesson (from political commentator Tom Houck) in 1965 but then waited almost 20 years before getting a license — on a Friday the 13th, no less — could possibly be trusted behind the wheel.

While joking about Lewis's driving is facetious, speculation about his effect on the City Council is serious. This is because Lewis, famous for the role he played in the civil rights movement, is largely an unknown quantity as a politician.

» PHOTOS: John Lewis Through the Years

» RELATED: As Rep. John Lewis turns 80, friends celebrate his courage

"I came in here not being a part of any established group. I'm not part of any structure," Lewis explains. "It's not that I'm a maverick. I'm just not obligated. All I brought with me were some set ideas about what government ought to be like."

If his inexperience and lack of public allegiance make Lewis unpredictable, it is his eminence that makes him dangerous. He has a reputation and a following that extends nationwide. But among his admirers are many who might oppose his views on public policy, including, on some issues, his old friend and ally in the civil rights movement, Mayor Andrew Young.

"I don't think there's ever been a person like John on the City Council," says fellow freshman Councilman Bill Campbell. "His commitment to an ideal that is unswerving frightens some people, just as it is often said that here in Atlanta some people in the black establishment feared Martin Luther King Jr.'s activism. The status quo always fears the uncontrollable."

Lewis has a history of butting heads with the status quo. "Those of us in the movement," he remembers, "were not only bucking the whites. We were defying the code of restraint that had always governed the black community. We broke with our families, and also with the old-guard black leadership, particularly in places where that leadership was strong, like Atlanta and Nashville."

Lewis first became involved in the civil rights movement in Nashville as a student at the American Baptist Theological Seminary at Fisk University. [EDITOR’S NOTE: The two schools were separate institutions and Lewis received degrees from both.] He had wanted to be a preacher since he was six years old, growing up on the 130-acre south Alabama farm that his father had bought for $300. The ambition had propelled him into becoming the first member of his family to attend college, but he had not been in school long before his religious aspirations had to make room for other activities. Lewis attended workshops in nonviolent protest held at a Methodist church, and in November and December of 1959, he and other workshop students began putting their lessons to work, staging sit-ins at the lunch counters of drugstores around Nashville. For Lewis, it was the beginning of a life's work.

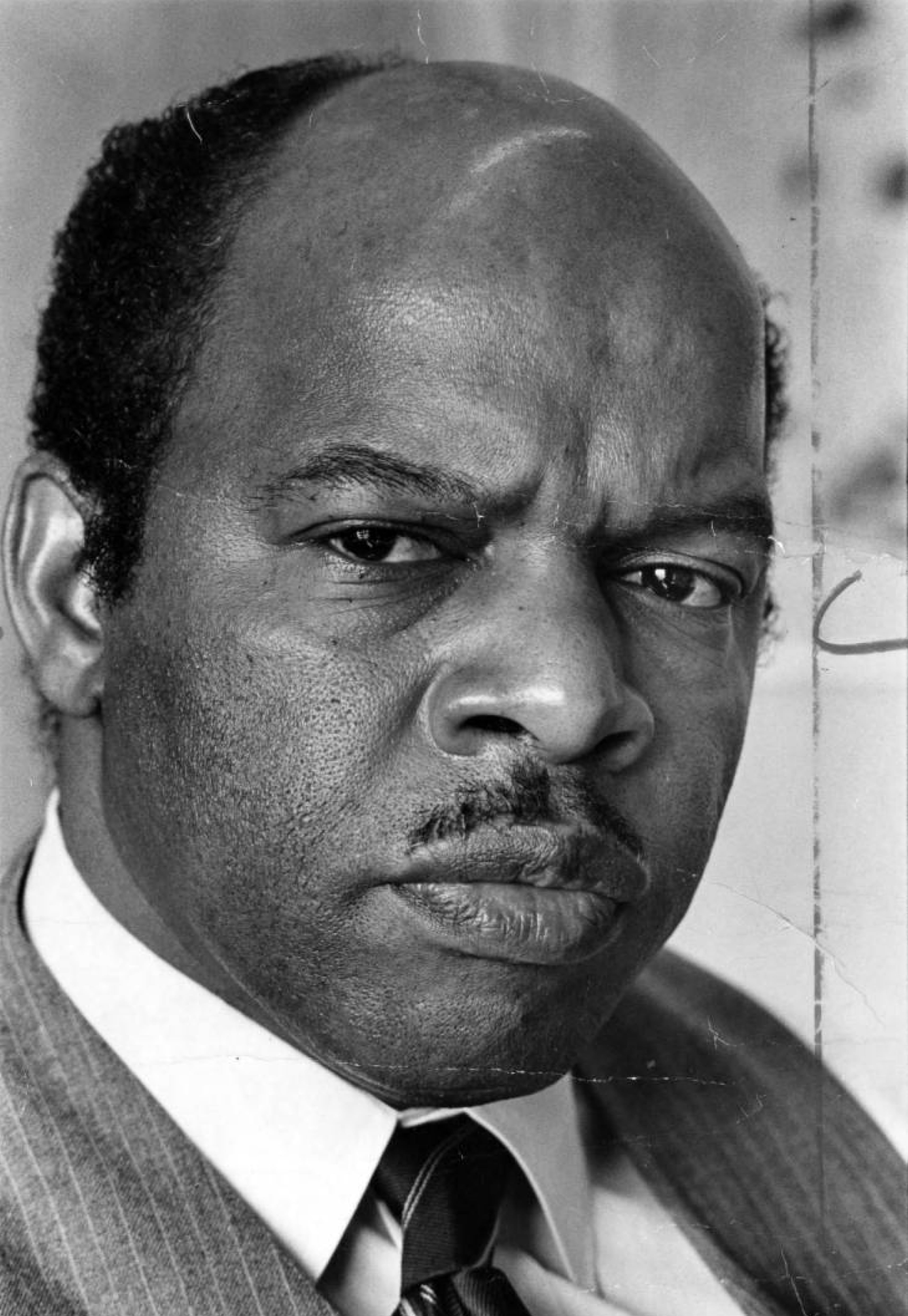

"Looking back," Lewis says now, "it's hard for one to believe that some things happened that happened." It's also hard for some to believe that Lewis played the part he did. Always a mild-mannered, almost pensive man, he has quiet eyes and, when his expression is serious, a slight pout to his mouth, as though he is in the midst of contemplating something and on the verge of telling you about it. In 1959, he seemed an unlikely candidate for exceptional bravery.

"People mistake John's personality for one that's easy to bend," explains Campbell. "He's so agreeable, he seems like the last person who could violently disagree with you."

But if Lewis wasn't violent, neither was he afraid of violence. "When things would get to the point where we were being threatened with billy clubs," state Senator Julian Bond remembers, "and everybody would stand around and say, 'Hmmmm, I don't know if I want to walk into that,' John would always say, 'Well, I'll go.' "

Lewis was among the first freedom riders to get off a bus in Rock Hill, South Carolina, on May 9, 1961, and he was beaten when he attempted to enter a white waiting room at the station. With Hosea Williams, Lewis led a march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge near Selma, Alabama, on March 7, 1965, and had his skull fractured by police billy clubs. In all he was beaten unconscious four times during civil rights demonstrations and jailed on more than 40 occasions.

Partly as a result of his courage in such incidents, he became a leader of the movement. He helped to found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In 1963, he became chairman of the organization, which was headquartered in Atlanta in the same building on Auburn Avenue as Martin Luther King Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

For Lewis the chairmanship of SNCC provided a pulpit from which to preach the doctrine he most fervently cared about. "In the early days of the movement," he says, "I talked about how civil rights leaders should take the lead in creating a sense of community where everyone lived together, black and white, in creating a place where people can live, work, play in harmony: the Beloved City."

"I try to take the position that what is good for the city, not a segment of it, is right. I don't want to be a hand-maiden of any particular segment of the population." —Atlanta City Councilman John Lewis

In 1966, Lewis lost the SNCC chairmanship to Stokley Carmichael, who was sympathetic to some members of the organization who preached a doctrine of black separatism. They argued that whites should be working in the white community, not participating in SNCC's leadership and organizing.

"Here we were talking about the building of an interracial democracy, a multiracial society," Lewis remembers, "and Stokely came along talking about black power — about getting whites out of the movement."

For SNCC, the change spelled the beginning of a period of increased militancy and internal dispute. Lewis soon left the organization, but he did not leave the movement.

Turning activism into politics

In Atlanta, Lewis headed the Voter Education Project, which he divorced from its parent Southern Regional Commission. His ability to remain a strong civil rights activist while staying clear of the internecine maneuvering and internal bickering that characterized much of the rest of the movement earned him a reputation as a pure-hearted, almost saintly individual. Still, his activity became more and more political. He worked on Andrew Young's congressional campaigns. When Young was appointed United Nations ambassador in 1977, Lewis ran for his congressional seat, losing in a runoff to Wyche Fowler. He then followed President Jimmy Carter to Washington, where he was head of ACTION until he quit to return to Atlanta in 1979.

For Lewis, as for Hosea Williams, Julian Bond and Andrew Young before him, politics seemed a natural extension of civil rights activism. "Everyone in the movement got in because they wanted to effect change," says Campbell. "Politics is just a natural extension of that."

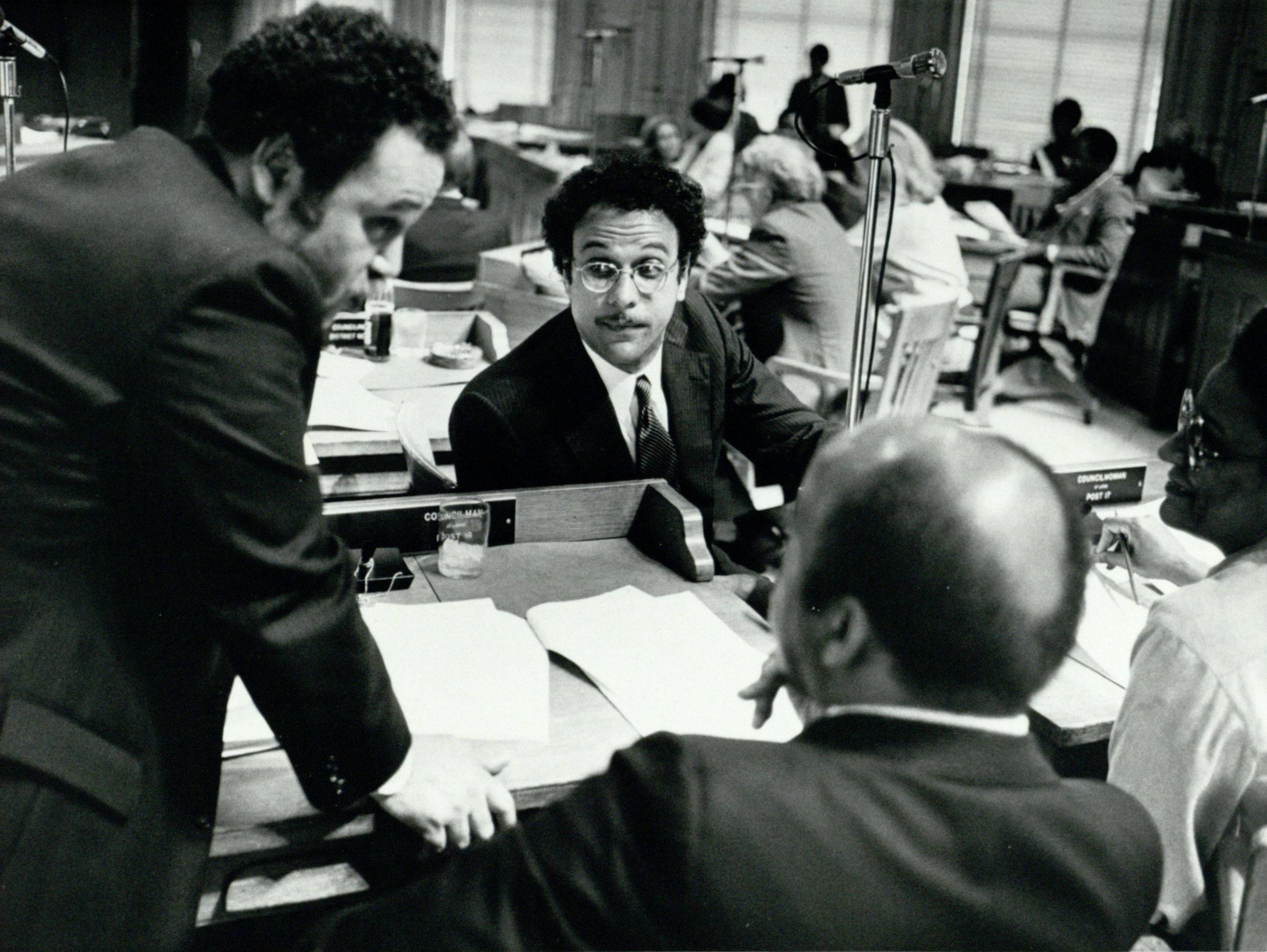

On October 7, 1981, Lewis won 68.8 percent of the vote to unseat a 24-year veteran of city politics, Councilman Jack Summers. It was a significant election for the city in several ways. Young's victory made Atlanta the first major city in the nation in which a black mayor had succeeded another black mayor. But perhaps more important was the shake-up of the council, which for the first time gained a black majority. The election of Lewis, Campbell and Myrtle Davis reflected more than ever before the diversity of political views in the black community.

It was Davis's election victory over Q.V. Williamson that best personified the split between old-guard and new-guard black City Council members. "Williamson was the anchor of the City Council," Bond explains. "Black council members used to meet at his home before council votes and decide the roles each member would take. Half the time the roles would fall through, but Q.V. lent an important coherency to the whole council." With Davis's election, the council as a whole, and its black contingent especially, began a process of realignment that is still going on.

For Lewis, coming into office occasioned a personal realignment. After years of working as an advocate, appealing to the powers-that-be, he was suddenly in power himself. A man with a reputation for intransigent idealism had entered a world where pragmatic wheeling and dealing is often the name of the game. "City politics is like prizefighting," Campbell says. "You can watch it and know all the ins and outs, but until you get into the ring, you don't really know what it's about."

How would Lewis fare in the ring? And how would his Beloved City survive the real world? The first test came soon, for before spring was over the council became embroiled in the most heated battle it had endured since the city government was reorganized in 1973. It was destined to be an especially tormenting trial for the freshman councilman who found himself in opposition to one of his oldest friends on an issue that was dear them both.

An early test

One morning in late June, Lewis went to the Canopy Castle, a hamburger emporium several doors down from Paschal's Motor Lodge on Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, at the invitation of fellow Councilman Ira Jackson, for what he thought would be a private and informal breakfast meeting of council members. But as Lewis arrived, he realized that the meeting would be neither private nor informal. Standing by the front door was one of Mayor Young's bodyguards, a policewoman.

"I was taken aback," Lewis remembers. "It was not supposed to be the mayor's meeting. But when I saw his bodyguard, I knew if she was there, the mayor must be, too."

Downstairs, in a wood-paneled room reserved for meetings, Lewis met a group of other council members and the mayor himself. The following week the council was to vote to accept or reject the mayor's plan for a Great Park surrounding a library dedicated to Jimmy Carter. The plan was controversial because it included a four-lane highway that neighborhood groups and some politicians, including Lewis, opposed. Those opponents had received intensive lobbying to get them to support the mayor, and that morning, they were about to get a personal appeal from Young.

The group sat down to a breakfast of eggs, sausage and grits. The mayor talked about the issues involved in his park plan. Eventually, he turned and looked across the table at Lewis. "Andy asked me to abstain," Lewis remembers. "He asked me not to vote my opposition to the road."

Lewis was on the spot. In the lobbying he and other council members had received from proponents of the Great Park plan road, the pragmatic issues peculiar to the park had been obscured by the issues of loyalty to the mayor and loyalty to the black community, which hoped that jobs connected with construction of the road would help ease its soaring unemployment. The issue of race was one that Lewis had never expected to be criticized on. The issue of loyalty to the mayor was one he was especially sensitive about, because he and Young had been friends since the early 1960s, when Lewis was chairman of SNCC and young worked for SCLC. The two had worked together on such projects as the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery.

"Almost from the first day of council I got in trouble, what I call good trouble." —Atlanta City Councilman John Lewis

In recent weeks, Lewis had discussed privately the Great Park issue with Young. But this was the first time that the mayor had asked him for a position in public, before a group of city politicians.

"There's no way I can abstain," he recalls saying to Young. "If I am present, I'm going to vote."

In Lewis's memory, that meeting was "the turning point in getting the Great Park plan passed. The mayor went to bat very effectively." The breakfast did nothing, however, to bridge the gulf between Lewis and Young on the issue, a gulf that had been growing almost since the day both were sworn in.

"Almost from the first day of council I got in trouble, what I call good trouble," Lewis says. "I think it was the first session of council, I introduced a resolution saying that 'Atlanta will go on record opposing a four-lane road through the Great Park.' It was passed unanimously by council, and the mayor signed it. Then one and a half, two months later, word came down that the mayor had a plan for a road. I was surprised, dismayed. I don't know, but my feeling is that even before the plan came into being, the mayor had made a commitment to President Carter and to [Department of Transportation Commissioner] Tom Moreland, that he was locked in and had to tell planners to include the road. [EDITOR’S NOTE: A smaller version of this road would eventually become Presidential Parkway, later named John Lewis Freedom Parkway.]

Lewis was convinced that the road would be a detriment not only to the neighborhoods through which it would pass, but for the city as a whole. He believed it would aggravate downtown traffic problems, aid the flight of businesses and middle-class residents to the suburbs, alienate tourists already put off by Atlanta's reliance on asphalt and automobiles and, in the long run, further deprive the poor, black inner-city communities that hoped to gain opportunity from the building of the road. "I don't think the people in the mayor's office ever really thought about what this would do for Atlanta," he says. "To this day, I don't know anything that would justify building it."

In the last couple of weeks before the council vote, the lobbying was targeted at black council members who, like Lewis, opposed the road. They were buttonholed not only by other politicians, but by influential constituents — ministers, campaign contributors, prominent businessmen. Increasingly, council members relate, the issues were overshadowed by racial rhetoric. The Black Slate, a lobbying group associated with the Shrine of the Black Madonna, published and distributed a bulletin equating a vote against the park plan with "a vote against the Mayor and against the Black Community."

Campbell recalls sound trucks rolling through neighborhoods "blaring that councilmen were not being loyal to the mayor. I thought it was politics at its worst," he says. "It was an incredible amount of pressure — although the mayor always acted in a very proper fashion."

"Some force put together a tremendous outpouring of support for the mayor," says Bond, who supported the road. "And some force made it a racial issue. It shouldn't have been a racial issue. There was nothing racial about it."

The mayor's office disavowed any involvement in the pressure levied against Lewis and other council members. "It was not a racial issue," says Angelo Fuster, a member of Young's staff responsible for lobbying with council members and community leaders on the Great Park plan. "The mayor didn't perceive it like that and didn't push it like that. Some people saw it that way, and not totally without cause. The plan was being opposed by all-white neighborhoods, and that was why some folks, not I or the mayor, saw it as a black versus white issue."

"Absolutely everybody opposed to John's position tried to talk to him," recalls Stanley Wise, one of Lewis's closest friends since both were involved in organizing for SNCC. "But I was at several meetings with the mayor where people were angry at John and wanted to pressure him, and Andy was quite opposed to that — he was adamant that people leave John alone."

Whether or not Young was responsible for the tactics used to sell the Great Park plan, they were acutely felt by Lewis. "Some people around Mayor Young went far beyond what was necessary," he says. "I got the feeling that people in the mayor's office wanted to win at any cost. Other people, too.

"One guy kinda suggested to me that 'We'll take care of your campaign debt if you'll support the mayor.' Other people I respected came to me and said, 'This is gonna hurt you if the mayor loses.'

"I knew I was not going to vote for it, but my position was hardened by the tactics that were used."

The price of independence

In the end, the Great Park plan, including the road, passed the City Council, with Lewis, Campbell and Davis, the three newly elected black council members, voting against it.

With that vote, Lewis lost, but survived his first great political battle as an elected official. For the first time as an insider, he had made a significant impact on the city's political deliberations and declared himself a strong force in Atlanta's future. But what that strength meant was unclear. Was the John Lewis who had been willing to buck the mayor and his other longtime allies on an important issue independent enough to be a tough player? Or was the John Lewis who refused to budge from a campaign position opposing the road too inflexible and idealistic to be effective in the hurly-burly trading and coalition-building of city politics?

Some observers see the dispute between Young and Lewis as an encouraging affirmation that their friendship will survive the rigors of politics. Others see scars that they don't expect to heal easily or quickly.

"The Great Park issue was very painful for John," says Campbell. "People he had worked with, marched with in Selma and Birmingham, were saying to him that he was disloyal to the mayor and favoring whites over blacks. It was so inconceivable to John that I don't think he's over it yet."

Campbell's analysis is echoed by John Sweet, a former city councilman from Inman Park who, like Lewis, was branded as an idealist. He says, "John has spent his entire life fighting against the misunderstanding of the white community. He's spent the last couple of months fighting against the misunderstanding of the black community. What he's found out is that everybody misunderstands."

Fuster is more cheerful. "John Lewis and the mayor share a vision of how things ought to be, to a great extent," he says. "In some circles it had been assumed that John Lewis would go along with the mayor, whatever the issue, because of their past friendship. Now he has shown that he is independent. If John and the mayor know that each other's opinions are heartfelt and honest, the combination of trust and independence will be a tremendously productive thing."

"The Great Park issue was very painful for John. People he had worked with, marched with in Selma and Birmingham, were saying to him that he was disloyal to the mayor and favoring whites over blacks." —Atlanta City Councilman Bill Campbell

Assessing his first nine months in office, Lewis himself comments, "It's been somewhat frustrating for those of us who are new here, for those of us who came in with a great deal of hope. Some people in the white business community, and the white community in general, and some people in the black community think that Bill Campbell, Myrtle Davis and I are too free, too independent, not part of any clique or group. So many people in politics are allied with different interests, with different segments. There are some who are community-oriented and some who are business-oriented. And that's fine, except that sometimes people will do things because of their alliances, regardless of wrong or right.

"That surprises me, the amount of trading — 'I'll do this for you, and you can do this for me.' In that environment it is hard for anyone who comes in and says, 'We're going to go straight down this road,' when that means crossing somebody's friend or interest.

"I try to take the position that what is good for the city, not a segment of it, is right. I don't want to be a hand-maiden of any particular segment of the population. To me there is something almost improper about that.

"I also don't want to be a one-issue council member. I don't want to be the guy that carries all the causes. I don't want to be the crusader. Some people say that age tends to make you a little more mellow, to moderate your ideas and thoughts, to make you less idealistic. I don't think I've changed. I've just decided I'm going to pace myself."