Fear, doubt linger over toxic emissions, as regulatory battle rages

Frank Austin was taking no chances. Seated in the first row of pews inside the old Newton County Courthouse, he unclipped a yellow and black device hooked to his belt.

“I have an ethylene oxide detector and I’ve been testing,” Austin said, as he waited to hear from the federal Environmental Protection Agency about emissions of the toxic gas in Covington.

On the detector’s screen, Austin called up readings as high as 5 parts per million that he said he detected near Becton Dickinson, the medical device and sterilization facility a few miles from where he owns property. Such a reading, if measured consistently over a 15-minute period, would equal the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s maximum exposure limit for workers on a factory floor.

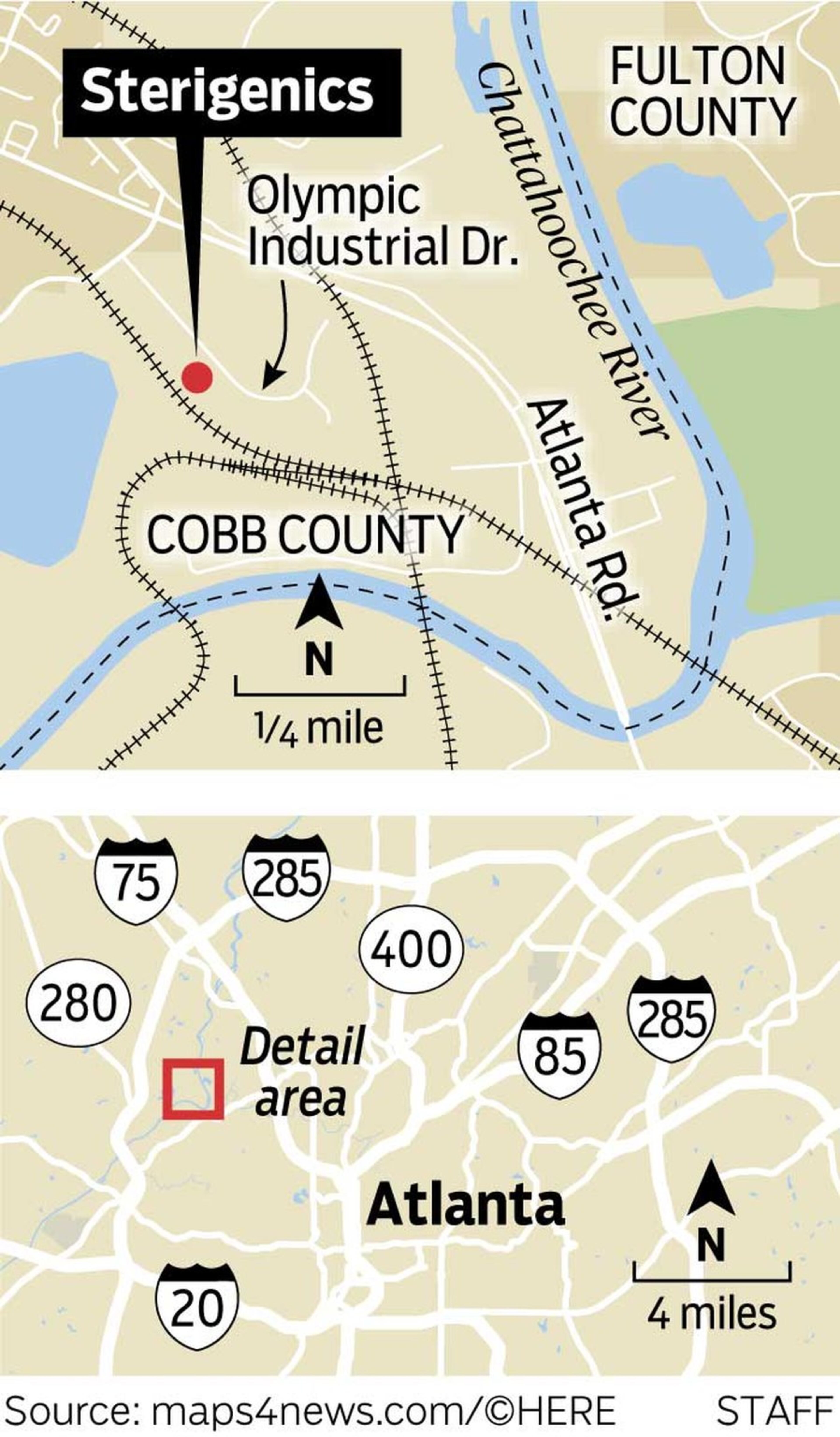

Austin, an architect by trade, bought the device a week earlier after he saw media reports about a 2018 federal study that warned of potentially high risks of cancer in census tracts near the BD plant in Covington and Sterigenics in Smyrna. Both plants use ethylene oxide to sterilize medical devices.

“Here, I’m getting zero,” Austin said, as more folks filed into the courthouse about two miles southwest of the plant formerly known as BD Bard. “I just have it running and wait for the alarms to go off.”

Austin was part of a standing-room-only crowd at Tuesday's town hall, anxious to know what state and federal environmental and health officials planned to do to ensure the safety of the air in Covington. A day earlier, more than 1,000 people packed a similar meeting in Marietta that focused on the Sterigenics facility and surrounding neighborhoods in Fulton and Cobb counties.

The cause for alarm was disclosure of a 2018 EPA report that identified two census tracts in Fulton near Sterigenics and another in Newton near BD that showed the potential for elevated risk of cancer from ethylene oxide exposure. Many of the anxious town hall participants had never heard of ethylene oxide, much less the health risk that it posed.

But the dangers of ethylene oxide and how to safely use it have been the subject of a decades-long battle between private industry and state and federal regulators.

The industry and EPA were already locked in a nearly year-long dispute over the findings of the 2018 EPA report before it erupted as a public health concern in Georgia last month.

The controversy pits companies that make and use ethylene oxide, or EtO, against the EPA’s scientists and epidemiologists charged with protecting the public’s health. And it unfolds at a time when the Trump administration has been relaxing environmental regulations.

In the latest skirmish over the 2018 report, the industry is pushing EPA to back off its regulation of ethylene oxide. The American Chemistry Council wants the agency to raise its threshold for the level of EtO exposure that poses a cancer risk, arguing that the human body can handle more and that the current threshold is based on flawed science. Raising it would allow plants to increase emissions.

On the ground in Georgia, the industry is taking a different tack, agreeing to new safety measures in a bid to remain operational.

Earlier this month, Sterigenics entered a consent decree with the Georgia Environmental Protection Division to improve its emissions controls. The company has said it will spend $2.5 million to upgrade its systems, including new equipment to capture “fugitive” emissions that might escape existing scrubbers.

After a testy meeting Tuesday with executives from both companies, Gov. Brian Kemp singled out BD and demanded the company follow Sterigenics’ lead.

“This proactive measure demonstrates (Sterigenics’) commitment to the local community and helps to restore confidence in its operations,” Kemp said. “Now BD Bard should do the same.”

A few hours later, BD said it had committed in writing to the governor to invest $8 million to upgrade its facilities in Covington and Madison.

“We are confident in our controls and that our emissions are not putting any of our communities at risk,” a company spokesman said in an email to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Both companies say their current controls already meet state and federal emissions standards.

But the actions thus far by government and the companies haven't satisfied many residents near the facilities. Two state Democratic lawmakers and U.S. Rep. David Scott, D-Atlanta, have called for the Sterigenics plant to be shut down until tests prove it is safe. U.S. Rep. Hank Johnson, D-Lithonia, who represents Covington, called for the same with BD.

Regulators and government officials have also felt the heat.

Bowing to public pressure, Georgia EPD said earlier this month it would conduct months-long air testing near the Smyrna and Covington plants. Cobb, Smyrna and Atlanta also announced they'd pay for their own independent testing.

An apology from EPA

Unbeknownst to most Georgians, the latest regulatory battle started a year ago last Thursday when the EPA published its National Air Toxics Assessment (NATA) on its website. The assessment, based on 2014 emissions data self-reported by industry, found potentially high cancer risks in 109 census tracts nationwide — including the three in Georgia — based on modeling, not air testing.

The elevated risks stemmed in part from the application of a lower EPA threshold for how much EtO exposure might cause cancer.

Industry contested the report a month after it was published. But the EPA chose not to issue press releases about the study, or take other measures to get the word out.

EPA did alert state agencies, such as Georgia’s EPD, providing talking points in English and Spanish in case the press or public stumbled across the report on the EPA website and called about it.

That call eventually came and the report went viral after WebMD and Georgia Health News published a story in July, prompting surprise and concern from residents near the two sterilization plants.

At the Marietta and Covington town hall meetings, nearly every resident who spoke to AJC reporters said they wanted to know why regulators kept them in the dark.

Ken Mitchell, deputy director of the EPA’s air and radiation office in the Southeast, told the AJC regulators weighed whether to publicize preliminary, possibly incomplete information or wait for more robust data.

“Do you tell people and cause alarm with a screening level analysis?” Mitchell said. “Or do you go and get harder facts on the ground that lets you determine if there really is a problem — and then you should tell people about it.”

On Tuesday, Mitchell was more contrite to the Covington crowd, apologizing for not publicizing the NATA report.

“I’m sorry this happened and next time the NATA comes out we will be much more thoughtful about how and when we communicate with the public,” he said.

He and other officials tried to soothe residents’ fears at the Marietta and Covington meetings.

The NATA assessment is a screening tool designed to flag potential problem areas for further examination, Mitchell said.

“It doesn’t tell you that there is a problem, only that there might be one that you need to look at more closely,” he said. “And that’s what Georgia EPD has been doing.”

New state EPD modeling, based on more recent emissions data self-reported by the companies, showed lower potential cancer risks surrounding the plants than the NATA report, Mitchell said, and EPA and EPD analyses over the coming months should determine if the 2018 NATA report really was a cause for alarm.

But deep public mistrust remains.

Sonya James moved to Covington 16 years ago from San Francisco. A neon T-shirt she wore to the town hall said “ETO Got to Go” with the name Bard crossed out.

James said she beat thyroid cancer and will be five years cancer-free next month. She said there’s no way for her to know if the factory had anything to do with her cancer, but she fears for her daughter who lives near the BD plant and for her two grandchildren who attend school less than two miles from the facility.

James, like many residents in Smyrna and Covington who spoke to the AJC, wants to see the facilities shut down.

“Air testing is not enough,” she said. “They need to move them out.”

A widely used gas

Ethylene oxide is considered a building block chemical that’s used in the manufacturing of other compounds and products. It’s a byproduct of fossil fuel refining. It’s used to make polyester fiber that goes in carpet, clothes and upholstery.

Sterigenics and BD both use the gas to sterilize single-use medical devices and products such as surgical kits, gowns, sutures and urinary catheters. The ethylene oxide sterilization method dates to the 1930s and it’s widely used because of its versatility.

The gas can penetrate packaging, meaning medical device companies can ship packaged goods to sterilizers who decontaminate the goods inside their original packaging and then return the products to manufacturers’ supply chains for distribution to hospitals and other medical facilities.

It’s also extremely flammable and for decades the industry and scientists have known exposure to ethylene oxide is harmful.

Kyle Steenland, an epidemiologist and professor at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health, conducted ground-breaking studies in the 1980s and 1990s of workers in medical sterilization plants across the U.S., finding higher rates of breast cancer and lymphoma deaths in workers exposed to high levels of EtO compared to those exposed to lower levels. His findings played into EtO being declared a carcinogen.

Steenland said residents living near a plant are probably more likely to be killed in a car crash than to contract cancer from breathing the air near a medical sterilization facility.

“I wouldn’t freak out about it, but I might try and limit exposure as much as possible,” Steenland said. “If EPA’s giving you a signal that this is the recommended level, I’d try to meet that. I wouldn’t be putting more out than you had to.”

The gas also is more prevalent that previously known. When communities around the country have tested for it they often find it in areas they weren’t expecting to or in higher concentrations than had been predicted, said Mitchell, the EPA deputy director.

Battle over the science

The EPA is in the process of drafting new rules regarding EtO, unleashing a fierce battle over standards among industry and environmental lobbying groups.

The American Chemistry Council rebutted the EPA’s 2018 air toxics assessment in a 70-page report issued last September. Heavy on technical details, the council argued that EPA was over blowing the hazard of airborne EtO. They argued that tiny increases in EtO exposure won’t do any harm since humans produce their own ethylene oxide naturally and are exposed to it in the air from vehicle exhaust fumes, cigarette smoke and decaying plants.

Then in June the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, viewed by environmentalists as being friendly to the state’s oil and gas industry, issued its own report that drew similar conclusions.

The Texas agency’s toxicology division is led by Michael Honeycutt, a science skeptic who has argued repeatedly that pollutants aren’t as harmful as the EPA says, and who was appointed chairman of the EPA’s Science Advisory board by former EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt.

Honeycutt and other Texas staffers declined interview requests, but in a statement the commission said the EPA’s assessment had “significant scientific shortcomings.” The ethylene oxide levels that EPA calls risky are actually 4,000 times lower than what could be breathed over a lifetime with no significant increased cancer risk, the Texas agency says.

“EPA’s selected assessment illogically predicts an unacceptably high health risk from ethylene oxide levels that are more than ten times lower than the smallest amounts that the body normally produces,” the statement said. “And, ambient air background levels alone far exceed EPA’s unacceptable levels.”

Worried about the hands-off regulatory approach of the Trump administration, environmental groups have also joined the fray, issuing their own assessments to the public and EPA that refute the claims made by the chemistry council and the Texas commission.

“If the Texas risk assessment gets finalized,” said Dan West, a lobbyist for the Natural Resources Defense Council, “and it’s looser than what’s currently on the books, and then EPA adopts that — then we’re back to a situation where this chemical is spewing into neighborhoods across the country.”

Michelle Mabson, a staff scientist for Earthjustice, which is urging the EPA to keep industry EtO emissions low, said the agency correctly focused on existing EtO levels in the environment and calculated how much additional exposure threatens those who spend their lives breathing air near a plant.

Ethylene oxide is a known “mutagenic compound,” or one capable of producing genetic mutations that can cause cancer, Mabson said.

“It can cause breast cancers. It can cause lymphoid cancer. It can cause leukemia,” Mabson said. “Those are all hallmarks of a mutagenic compound, and it needs to be treated as such.”

Some look to Illinois

While Gov. Kemp and Georgia’s EPD have chosen to allow BD and Sterigenics to remain open while they upgrade emission controls, the Illinois governor and state regulators shut down a Sterigenics plant in February over concerns about ethylene oxide emissions that erupted last year.

A proposed consent order would allow the plant to re-open only after rigorous new emissions controls were installed, tested and lower emissions verified.

“Why can’t we get the same deal as Illinois?” said state Sen. Jen Jordan, D-Atlanta.

Jordan said uncertainty about ethylene oxide hangs over everyone’s heads. Intercontinental Hotels Group, parent company of Holiday Inn, Kimpton and Hotel Indigo, temporarily closed its design center near the Smyrna Sterigenics facility out of “an abundance of caution,” the company said.

Jordan said other companies have expressed fears to her about operating near the facility, and homeowners are concerned about their property values. The stigma of a potential health hazard could linger even if environmental regulators determine all risks have been abated, she said.

Phil Macnabb, president of Sterigenics, said calls to shut down the plants are shortsighted.

Sterigenics in Smyrna operates 24-7 every day of the year and sterilizes about 1 million products per day.

“The other side of this is there are patients at the end of the process who need the products we sterilize,” Macnabb said.

While the Illinois plant is closed, Macnabb said sterilizers have tried to shift the business to other facilities across the country, “but there’s not a lot of capacity out there.”

“The supply chain of medical devices is usually a couple of weeks,” he said. “You don’t want medical devices sitting in inventory very long and risk contamination. My customers and the patients can’t risk a longer shutdown.”

The story so far

A 2018 EPA study flagged two census tracts in Fulton County near the Sterigenics facility in Smyrna and another in Newton County near the Becton Dickinson plant in Covington as having the potential for increased long-term risk of cancer because of exposure to ethylene oxide. Both plants use the gas to sterilize medical equipment. Bowing to public pressure, the companies have agreed to new emissions controls and the state has said it will conduct air testing to further assess whether there’s a risk to public health. State and federal regulators faced anxious crowds in town hall meetings Aug. 19 and 20.

Timeline of ethylene oxide sterilization in Georgia

Ethylene oxide sterilization dates back to the 1930s and the practice is widely used to sterilize medical devices and fumigate agricultural products.

1967: The medical device manufacturing and sterilization facility now operated by Beckton Dickinson (BD) opens in Covington.

1972: The sterilization facility now operated by Sterigenics opens in Smyrna.

1991: The Covington plant opens its current ethylene oxide sterilization facility.

1994: The federal Environmental Protection Agency approves new ethylene oxide emissions rules that include requiring back vents, apart of the ventilation system used in sterilization chambers, to be connected to environmental controls.

1997: A series of fires and explosions occur at sterilization facilities involving the back vent. After investigations, the EPA decides to suspend the back vent rule.

1997: BD says the back vents at its facilities are connected to emissions systems and have been ever since.

2001: The EPA formally removes the back vent emission control rule. Though some states enact their own rule, Georgia does not.

2006: BD opens a second sterilization facility in Madison.

2015: Sterigenics says it connects its back vent to its emission control system and self-reports a nearly 94 percent decrease in emissions from its Smyrna plant.

2016: EPA classifies ethylene oxide as a carcinogen.

August 2018: EPA releases its 2018 National Air Toxics Assessment that flagged 109 census tracts nationwide for potentially high-risk for cancer from long-term exposure to carcinogens. Three census tracts in Georgia near the Sterigenics and BD plants are flagged related to potential exposure to ethylene oxide.

July to August: Media reports trigger a public backlash. State EPD announces an agreement with Sterigenics to improve emissions controls. BD also commits to emissions improvements.

Sources: Sterigenics, Becton Dickinson, EPA and EPD.