She wasn’t supposed to be there, stuck in a unit where sick inmates had been quarantined as COVID-19 began to spread through the United States Penitentiary in Atlanta.

“She wanted to be moved. She asked to be moved,” Robin Grubbs’ father, Gary Grubbs, told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “I don’t know why they didn’t listen to her.”

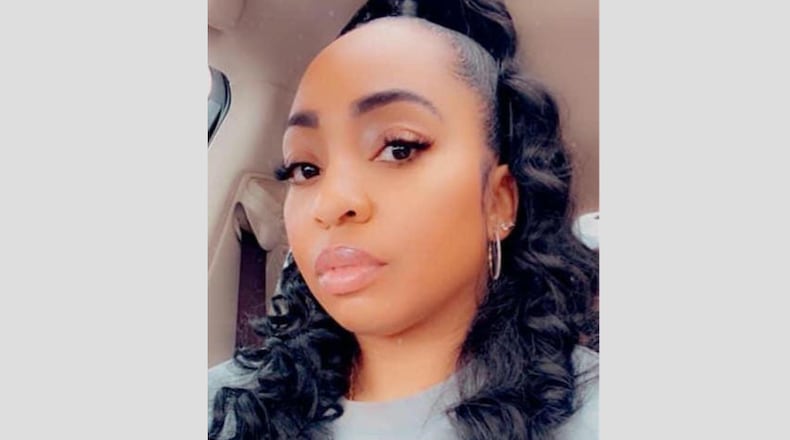

The U.S. Bureau of Prisons confirmed the late Grubbs, 39, had tested positive for the coronavirus but, according to a spokesman, “there is no information or evidence relating to a cause of death.” The bureau is awaiting autopsy results.

RELATED: Eligible for home release, inmates remain at Atlanta federal prison

“We can acknowledge the death of an employee at USP Atlanta, however, there is no information or evidence relating to a cause of death,” BOP spokesman Scott Taylor said in a written statement.

The bureau previously stated Grubbs had been “successfully screened prior to entry and was asymptomatic.”

But a federal lawsuit filed by an inmate at the federal prison confirms previous reports that Grubbs had asked to be moved out of Unit B-3. The suit also raises more questions about how the prison is handling has handled the coronavirus.

UNPROTECTED AND UNRELEASED

Inmate Michael Fiorito, 52, said Grubbs, who was a case manager, told him on March 23 that she was not provided with any personal protective equipment -- a complaint she also shared with her father.

Prison officials confirm Grubbs had been promoted a month before her death. It’s unclear why she was kept at her old post.

Fiorito, convicted in Minnesota of mail fraud, is suing in hopes of being approved for home confinement. He said he suffers from rheumatoid arthritis and is taking medication for lupus that weakens his immune system.

“I meet all the criteria to be released,” he said.

Just last month, U.S. Attorney General William Barr’s urged officials to “immediately maximize” the release of prisoners -- focusing on the most medically vulnerable -- to prevent the spread of the virus.

The BOP has placed an additional 1,871 inmates on home confinement since then, an increase of 65.6 percent. That accounts for less than one percent of the nation’s overall prison population.

The BOP did not provide numbers for the Atlanta prison, but the AJC has learned, through interviews with offenders and their family members, that several inmates eligible for release remain incarcerated.

In a statement, the BOP noted that Barr’s order focused on prisons with the highest infection rates, such as Oakdale in Louisiana and Danbury in Connecticut.

“Case management staff are urgently reviewing all inmates to determine which ones meet the criteria established by the Attorney General,” the statement continued.

The wife of one offender, a former medical professional serving time at the minimum security Atlanta Prison Camp, said her husband, who’s in his late 60s and suffers from high blood pressure, thought he would be home now. He told the AJC last month he was expecting to be one of 17 inmates from the camp approved for offsite confinement following a two-week quarantine at the main prison.

He remains at the camp, along with 139 other offenders. He and his wife didn’t want their names published, fearing reprisal.

According to the BOP, seven inmates and six staffers have tested positive for COVID-19 at the Atlanta facility, which currently houses 1997 prisoners. That does not include all infections, just those currently infected.

“The total number of open, positive test, COVID-19 cases fluctuates up and down as new cases are added and resolved cases are removed,” Taylor said.

Currently, 1692 federal inmates and 349 have contracted the virus. But many experts believe the real number is much higher.

The non-profit Marshall Project notes that BOP will not say how many prisoners have been tested. Of those who have, 70 percent were found to be positive, according to the bureau's own figures.

“HOW DID I GET SO LUCKY?”

Robin Grubbs, who had lived in Atlanta for six years, was buried in her native Augusta, according to her obituary.

Gary Grubbs last saw his daughter two days before her death on April 14. He and his wife had brought her a care package. Robin Grubbs showed it off on social media, writing, “Airhugs because Corona is everywhere at this point... How did I get so lucky?"

“She seemed fine,” he said.

They talked again on the phone a day later.

“Still seemed okay,” her father said.

Gary Grubbs said he’s determined to find out why his daughter remained in her old post one month after her promotion. And why she was forced to work without PPE.

“I’m trying to find out the answers,” he said. In the background his wife can be heard crying.

“We’re still dealing with this,” Grubb said quietly before hanging up the phone.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured