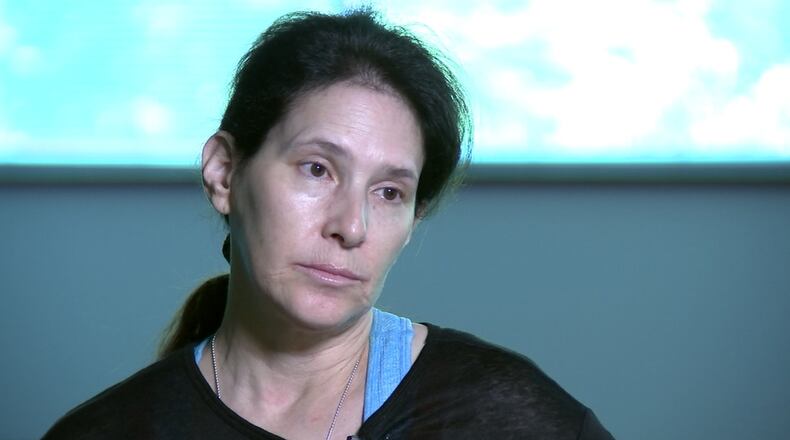

Jacqueline Mogan thought she had more than $1,600, but what she saw when she logged into her bank account made her stomach turn. Someone had cleaned out every last cent.

The Cumming woman’s bank could tell her her little, but Mogan said she did learn this: Cooling & Winter, a law firm of which she had never heard, had seized all her money to pay off a debt that she believes she never owed.

“How was I going to eat?” said Mogan, 51, who works two jobs to support herself and her ailing mother, who is 74. She went for three weeks without that cash, relying on a family loan to get by.

When Mogan’s money vanished, she joined thousands of consumers who have had their savings seized directly from their bank accounts by debt collection firms. In Georgia, it can be legal for a debt firm to empty out a customer’s entire account to pay off an old credit card bill or other household debt.

To do so, these firms must follow state and federal rules that critics say don’t go far enough to ensure that the debt is legitimate, and that collectors are taking money from the right people. The industry is beset with complaints that its collectors repeatedly break what rules that do exist.

In Mogan’s case, that collections company is Cooling & Winter, a Marietta law firm whose partners drew federal scrutiny even before the firm’s December 2015 launch. When they were partners in Frederick J. Hanna & Associates just three years ago, Joseph Cooling, Robert Winters and Hanna were fined for running what the federal Consumer Financial Protection Board called a “debt mill,” a description that Cooling & Winters’ attorney disputes.

Cooling & Winter followed the law, said S. Louis Schiappa, an attorney for the firm.

“At the end of the day, debt collection is unpopular for some people. We try to do everything the right way and follow the rules and make impact as soft as possible under the rules,” Schiappa said.

Still, complaints from Mogan and others on Cooling & Winter have consumer advocates wondering whether state protections need strengthening, and whether regulators need to investigate.

“It’s easy to game the system and basically just go after people who don’t know how to defend themselves,” said Rachel Lazarus, an attorney with Atlanta Legal Aid, which handles consumer protection complaints. “It’s a very cynical way to make money.”

‘A factory’

Cooling and Winter’s former firm Frederick J. Hanna & Associates had a years-long history of trouble. The state consumer protection agency received so many complaints that it launched an investigation into the company in 2008.

That firm’s impact on Georgia residents was vast, according to CFPB figures. In this state alone, Frederick J. Hanna & Associates sued about 78,000 consumers in 2009 and 84,000 in 2010, according to the CFPB. Consumers complained to what was then the Governor’s Office for Consumer Protection that the Marietta firm used deceit and abusive tactics to collect money from consumers, even when they did not owe it.

The firm argued those tactics were none of the state agency’s business. Nearly two years later, the Georgia Supreme Court said Frederick J. Hanna & Associates were right. Only the State Bar of Georgia, which disciplines lawyers, could regulate the firm in this state.

The Bar issued no public sanctions on Hanna, Cooling or Winter, but the CFPB did. A suit by the federal agency said Frederick J. Hanna & Associates made millions by being slipshod with the facts and the law. The firm filed so many debt collection cases that its lawyers were barely involved in any of them, and routinely filed false affidavits in court, the consumer watchdog agency said.

“To produce so many lawsuits, the Firm operates less like a law firm than a factory,” according to an agency filing in federal court. Its attorneys were expected to spend less than a minute reviewing each suit.

Frederick J. Hanna & Associates and its partners admitted no guilt in the CFPB agreement, but they did concede to a $3.1 million fine and federal monitoring of any successor companies. CFPB also blocked the firm's partners from the practices that regulators investigated.

That same month, Cooling and Winter launched their own firm, according to filings with the Georgia Secretary of State. On March 4, 2016, it received its first public complaint with the CFPB. Sixteen days later they were sued for the first time in federal court by a consumer who said they were trying to collect money he did not owe.

By September 1, the CFPB logged more than 100 complaints against Cooling & Winter in its public database.

The CFPB failed to respond to repeated calls and emails over several weeks asking whether the Frederick J. Hanna attorneys named in the settlement agreement remain in compliance with its terms.

Common problems

Mogan’s case is pockmarked with the kinds of problems that regulators and consumer advocates have complained about for years.

The alleged debt dates from 2005, resembling what critics sometimes refer to as “zombie debt.” Under Georgia law, a firm must receive a court judgment affirming that the consumer owes the debt, then renew their right every few years to collect it. This means that in an expert’s hands, a debt can live for decades.

Mogan said she never lived at the house where the debt holder said it served her in 2005 with notice they were suing her over the debt. The industry is rife with complaints of “sewer service,” where process servers claim they notified a defendant of a suit when they did not.

And because Mogan never appeared at the 2005 hearing, the holder of the debt did not have to produce proof that Mogan owed the money. In Georgia and elsewhere, a judge may automatically rule for the debt holder if a defendant doesn’t make it to court.

Other states such as New York, North Carolina and Maryland passed laws to shield consumers against some of these problems, but they’re rare.

“While some of these (protections) currently exist, they aren’t necessarily widespread or universally available to consumers,” said April Kuehnhoff, an expert on debt collection with the National Consumer Law Center. The debt collection industry hopes to loosen those protections further in a bill pending before the U.S. House of Representatives, she said.

Research shows that between 91 and 99 percent of consumers who are sued over debt are not represented by lawyers, according to the NCLC, but Mogan did find Robert Schwartz, a local attorney who took on her case for free.

Schwartz discovered that the business Cooling & Winter says it represents in Mogan’s case no longer exists. Phoenix Accounts Receivable III was administratively dissolved in May 2008. Schwartz wants to know whether the debt firm followed the rules.

“They shouldn’t be out there seizing money on behalf of entities that don’t exist,” Schwartz said.

“I have no problem with legitimate debt collectors. People owe money,” Schwartz said. “But we all have to go by the book.”

After a Channel 2 Action News producer informed a judge it intended to sit in on a hearing in Mogan’s case, Cooling & Winter dropped its suit. In a settlement agreement, the firm agreed to pay Mogan for her expenses and will not block her efforts in court to get the debt off the books. Her bank returned the money.

After Mogan fought back in court, Cooling & Winter’s staff researched her address history and found that she may have not lived at the house where she was served in 2005 after all, attorney Schiappa said. This would make the debt invalid, so they dropped the case.

“This is not evidence that anything improper happened,” Schiappa said. It’s proof that someone made a mistake 13 years ago. Beyond the judgment, the firm does not have proof in its possession that Mogan owes the debt, Schiappa said.

Mogan won her battle, but worries that other consumers aren’t so lucky, and are stuck paying debts they don’t owe.

“These people need to be shut down,” Mogan said of Cooling & Winter. “It’s just not fair.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured