As Confederate statues topple, groups target Decatur’s monument

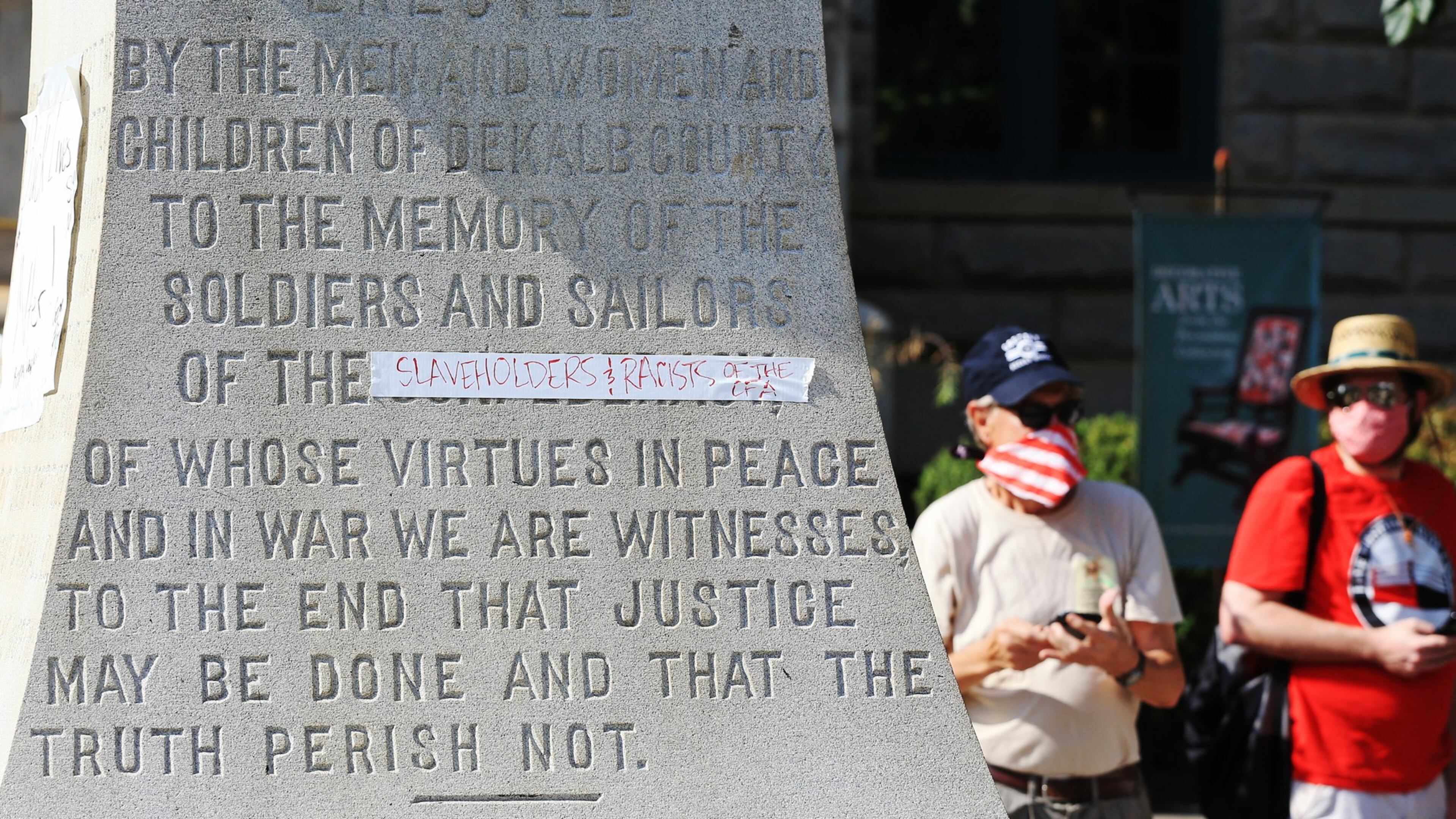

For a few years, DeKalb County leaders tried to find a way to legally dispose of the Lost Cause monument at the heart of the Decatur Square. They had no luck, settling last fall for the addition of a marker that provides more context to the 30-foot obelisk that was erected nearly half a century after the Civil War.

But now, in the wake of police killings that have sparked protests across the country, local community activists are renewing their calls for DeKalb’s monument to come down — and asking government officials to defy Georgia law to make it happen.

“I think it’s going to take political will from our leaders in the city and the county to defy a unjust law,” Sara Patenaude, aleader of a group called Hate Free Decatur, said this week.

“That can be the only response,” added Fonta High, a member of the Beacon Hill Black Alliance for Human Rights.

The ongoing nationwide protests were sparked by the police killings of George Floyd in Minneapolis and Breonna Taylor in Louisville, as well the death of Ahmaud Arbery in South Georgia. All three victims were black. Three white men have been charged in Arbery's death.

The protests have tried to bring attention to systemic racism within law enforcement as well as American culture. Confederate monuments, long targets for protests and vandals alike, have landed back in the spotlight.

A statue in Alexandria, Virginia, was taken down a few days ago,and another in Richmond appears destined for the same fate. In Alabama, officials have already removed Confederate monuments in Birmingham and Mobile; another in Montgomery was toppled by protesters.

In Athens, some 60 miles east of Decatur, Mayor Kelly Girtz has said he’s trying to figure out how to remove a prominent monument at the heart of the city.

"We want it gone and gone quickly," he said Wednesday, according to the Athens Banner-Herald.

Opposition to Decatur’s monument — which suggests that Confederate soldiers were fighting solely for states’ rights — is garnering momentum.

Earlier this week, the editor of a well-read local news site, Decaturish, published an editorial calling for officials to remove the monument "before someone in the community hurts themselves trying to do it for you." The Beacon Hill Black Alliance and Hate Free Decatur have launched new campaigns to flood the phone lines and email inboxes of city and county officials.

They’re holding a rally Sunday afternoon.

The city of Decatur, meanwhile, recently allocated $50,000 to directly address racism and plan training sessions and community town halls. That move was largely driven by recent controversial incidents within the city that, historically, has a progressive reputation. In the last month-plus, three separate videos have emerged showing white students using racial epithets for black people.

But Mayor Patti Garrett said the discussion should also include “symbols that exist right next to our square,” and that she would “like to start that conversation up again at the state level.”

In a recent letter to the community about racism, the Decatur City Commission pledged "to work with DeKalb and state elected leaders to remove symbols of hate from the city."

Locally, there’s near unanimous agreement that the monument should come down. But working within the system hasn’t been and won’t be easy.

Beacon Hill and Hate Free Decatur first pushed for the removal of the Decatur monument in the wake of the deadly 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia,where white supremacists gathered to protest the removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee.

At the time, Georgia state law prohibited monuments from being taken down but allowed for relocation in certain circumstances. By early 2018, the DeKalb commission had put out a formal call for anyone willing to take the monument off their hands.

There were no takers.

In March of last year — around the same time the General Assembly adopted a measure making it even more difficult to remove monuments — the DeKalb County commission approved the addition of a "contextualizing marker" near the monument.

The marker, which says the monument was erected to "glorify the 'lost cause' of the Confederacy" and has "bolstered white supremacy and faulty history," was installed in September.

A few months later, the county commission unanimously passed a resolution asking the legislature to repeal the section of state law “which limits actions taken by counties vis-a-vis confederate monuments located on county-owned property.” A bill to that effect was sponsored last year by state Sen. Elena Parent but went nowhere in the Republican-led legislature.

DeKalb County CEO Michael Thurmond, who is also a published historian, is quick to distinguish the Decatur monument as one commemorating not the reality of the Civil War but the Lost Cause movement. Thurmond described it as an homage to a mythology aimed at denying slavery’s role in the war, stoking fear and reinforcing segregation.

He said such monuments have no place in the public square.

But he demurred when asked about the possibility of violating state law, removing the statue and seeing what happens.

“All we can do is continue to rebuild and unveil the truth, and build consensus across political lines and hopefully come to a final resolution,” Thurmond said. “That’s all you can do. Because it’s going to continue to flare up and reassert itself time and time again.”

Not all agree that Confederate monuments should be a focus right now.

State Rep. Renitta Shannon, whose district includes the eastern half of Decatur, believes the monument should be removed and has previously sponsored legislation that would allow it to happen. But Shannon, who is black, said white allies who really want to help should be pushing their government leaders on things like police accountability.

“This is a feel-good measure but the focus right now needs to be on driving accountability for the police and solutions that ensure police stop killing black people,” she said. “Anything else takes away from the focus.”

Patenaude, the Hate Free Decatur leader, is white. She said she understands that both symbols and systems need to change and called removing the monument “a simple fix” that would allow attention to be refocused elsewhere.

She was quick to point out that Hate Free Decatur is following the lead of the Beacon Hill Black Alliance, which is named for Decatur’s historical black neighborhood.

“These two (issues) are connected,” High, a member of that group, said. “We believe at the root of it is white supremacy and structural racism. These are not separate issues. That’s why this is the time.”