Among the haves and have-nots of Georgia health care, the young patients at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta are about to have a whole lot more.

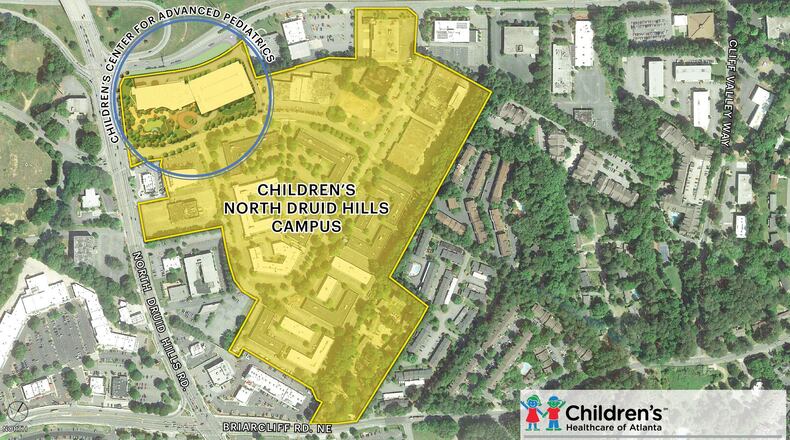

Defying a tough financial landscape for hospitals, CHOA recently announced a massive expansion to be built on 45 acres it owns near I-85 in Brookhaven. Just weeks after one rural Georgia emergency room announced it would shutter, CHOA said it expected to spend as much as $1.3 billion on the new facility.

PHOTO GALLERY: Healing spaces in Atlanta

The new campus will hold an expanded replacement for CHOA's current Egleston hospital at Emory University, as well as a new facility for the most complex diseases children face and leading-edge research in the lucrative field of outpatient care. The planning alone may take 18 months.

“Last year, we were starting to see times when we were completely full; we had no beds,” said Children’s CEO Donna Hyland. “By far the best option was to build.”

It's a stark contrast to daily cries in Washington and here at home of a broken health care system. Three weeks before Children's announced its plans this February, rural Cook County's medical center announced its emergency room would close for lack of funds, even though the county's population has grown and its number of uninsured has dropped.

Nationally, a Kaiser Family Foundation study found medical bills impacted the lives of a quarter of all working-age American adults, from vacations stalled to emptied savings accounts.

It’s a “crazy industry,” said Chris Kane, a health care strategist in Atlanta. “These hospital CEOs and boards are left with a complex puzzle because they’ve got to find a way for it to work.”

By all appearances, CHOA has.

Construction is already underway at the new site at I-85 and North Druid Hills Road. The Center for Advanced Pediatrics is a 260,000-square-foot facility for state-of-the art study and care of the most complex conditions. Many children will get care there that they could probably not get anywhere else.

At the same campus, the $1 billion to $1.3 billion hospital will take over the functions of the Egleston hospital at Emory, and meet projected demand through 2036. CHOA hasn’t decided what to do with the current Egleston building once its functions move to the new site.

The new hospital will add to the CHOA’s 622 beds, helping bring the three-hospital health system to perhaps 750 beds by 2026. CHOA’s other hospitals at Scottish Rite and Hughes Spalding will also continue to grow.

A question of competition

CHOA has advantages many hospitals do not.

It treats children, almost all of whom are insured, if not by private insurance then by Medicaid. It’s got a healthy fundraising operation. It’s got some leverage in negotiating prices with insurance companies, because companies want to offer clients a roster of hospitals that includes Children’s.

In a sort of rich-get-richer function of business, CHOA’s financial success gives it good rates on borrowing money. Year after year, bond ratings agencies give it the second or third highest possible grade.

Success breeds success in medicine, too. By consolidating all of the metro area’s freestanding pediatric hospitals, CHOA has more to offer quality pediatricians looking for a job, and families looking for a hospital. That includes families who have private insurance and can choose where to go.

That’s the rub.

“Certainly it’s important to have specialized services available to everyone in a community or state; for example, children with complex health needs,” said Dr. John Ayanian, director of the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation at the University of Michigan, who studied the impact of Medicaid expansion under Obamacare on hospitals there.

MAP: Rural hospitals in Georgia

EMERGENCY: The crisis at Georgia’s rural hospitals

But there’s also a possibility that hospitals with advantages like CHOA’s can siphon away some paying patients that other hospitals could have treated, Ayanian said.

In Georgia, some of those other hospitals, especially in rural areas, may be burdened with a problem CHOA doesn't have: uninsured adult patients who don't qualify for Medicaid, the government health program for low-income Americans.

Even in the metro area, there may be business that could be done elsewhere that CHOA will get just because of its image.

“If your kid had a broken bone, that may be true that they could go to any hospital and they’d say we X-rayed it, the kid has a broken bone,” said Kane, the strategist. “The public, their preference may be, ‘I need CHOA.’”

Dr. Ninfa Saunders, CEO of Navicent Health, which owns Macon’s pediatric hospital, said CHOA’s expansion is good news. She’s glad CHOA’s there to take referrals from her hospital and others in the state. But, she said, health care must be locally based.

“You have an advanced hospital that takes very complicated cases that we cannot handle,” Saunders said. “That is what we want for the children of Georgia. But what we also want is to make sure that this expansion doesn’t put all the children’s hospitals in the state and children’s units in a compromised situation.”

Good money, good care

Children’s was reluctant to discuss its financial details with the AJC. But bond disclosures and documents filed with the state show that in 2015 it made a whopping 28.7 percent profit on admissions to the Egleston hospital, and 24.1 percent off admissions at its other main hospital, Scottish Rite, while the much smaller Hughes Spalding hospital lost money on admissions.

As a not-for-profit organization, Children’s plows all of that money back into its work. And as CHOA points out, 60 percent of its admitted patients are on Medicaid.

Credit: Johnny Edwards

Credit: Johnny Edwards

Overall, CHOA, a $1.5 billion annual business, reported making $190 million after expenses in just the first nine months of 2016. CHOA officials point out that $45 million of that is due to investment returns and other figures that veer up and down from year to year. And they put the healthy coverage down to efficient management and leveraging the operation’s scale and focus.

That money pays for good care.

A tour of the Egleston hospital, which the expansion hospital will replace, showed remarkable attention to what works for children.

Enormous effort is taken to reduce children’s stress. Hospital officials say that improves the chances of good physical outcomes.

Patients’ own beds are a safe space, devoid of “pricks and pokes.” If a child needs a shot, a procedure or an IV inserted, they’re taken to a designated place for that. A neonatal ward at first seems shut down — quiet, almost warm and flanked by darkened alcoves — until you realize a dozen babies lie swaddled in those alcoves. Hospital officials say they’re not sedated; they’re just healing in silence, calmed by the womb-like atmosphere.

Walk down the hall and you may pass a staff dog, one of twelve trained therapy dogs maintained full-time by CHOA. Or photos of the hospital’s social workers, trained in dealing with children and families. You may pass a shelf holding what you realize is an Emmy, won by a staff videographer who documented a moving story from the hospital.

Downstairs in the lobby, a decked-out radio studio beckons through glass walls. Local celebrities occasionally talk to patients there and broadcast in the hospital.

But all that is a sideshow to the main attraction, the special pediatric expertise and equipment, all in one place.

With the new location, there will only be more of that.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured