AJC Deja News: Harvard student W.E.B. Du Bois quite an orator (1890)

Today’s AJC Deja News comes to you from the Sunday, May 11, 1890, edition of The Atlanta Constitution.

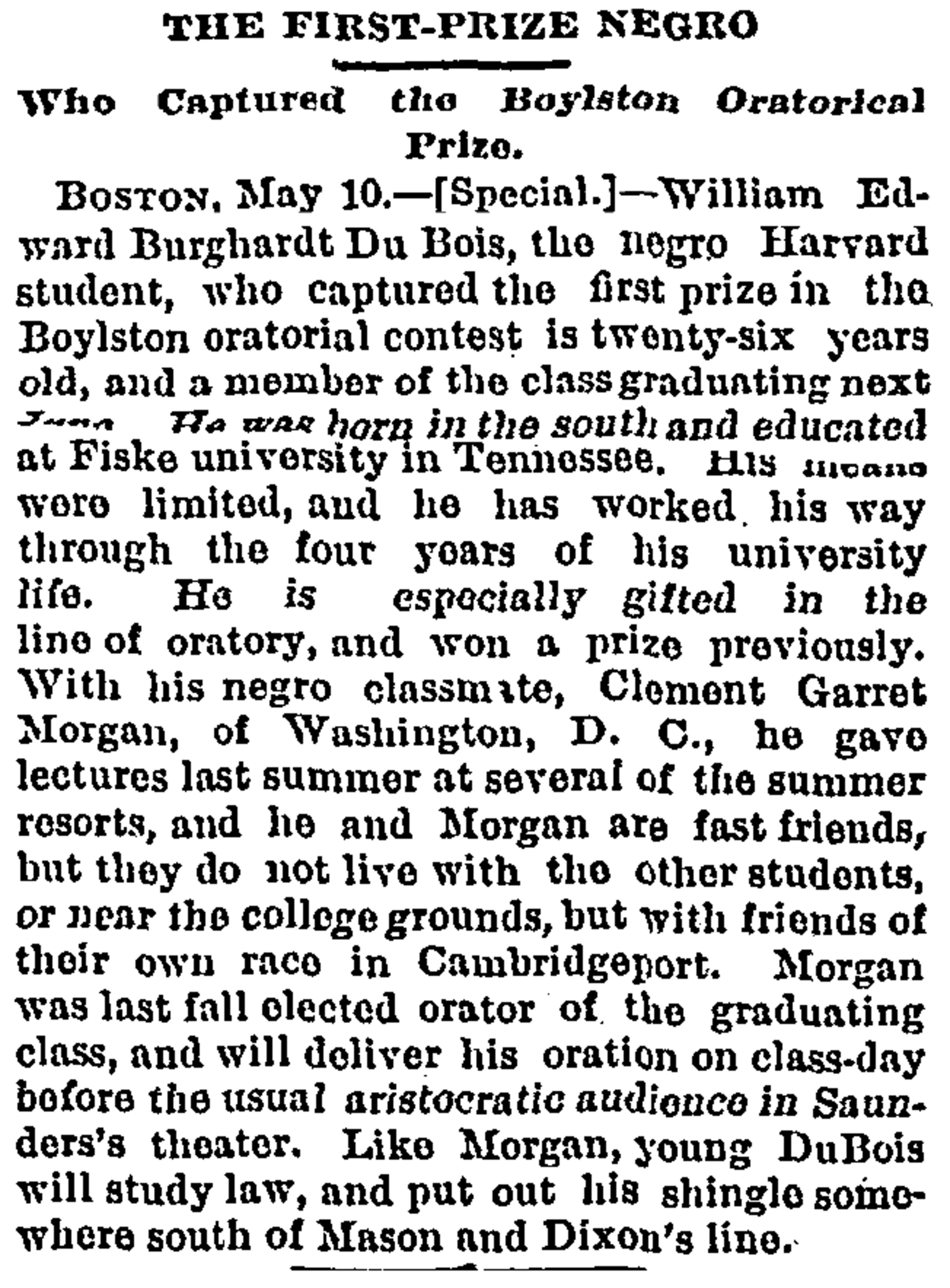

THE FIRST-PRIZE NEGRO: WHO CAPTURED THE BOYLSTON ORATORICAL PRIZE

In a dispatch from Boston, the Atlanta Constitution reported on a notable member of Harvard’s senior class—a black student named William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, who captured first prize in the school’s oratorical competition.

W.E.B. Du Bois would go on to become one of the most influential American scholars and activists of the 20th century, cementing much of his reputation while working as a professor at Atlanta University (today's Clark Atlanta) from 1897-1910.

All of that was ahead of him when the Atlanta Constitution described him as 26 years old, “born in the south and educated at Fiske [sic] university in Tennessee,” and “especially gifted in the line of oratory.”

In truth, he was 22 years old, having to repeat two years of college because Harvard wouldn’t recognize his credits from Fisk University.

The article’s assumption that he was a son of the South whose “means were limited,” was also way off. He was actually born in Massachusetts, had a comfortable childhood and attended integrated schools before traveling to Tennessee for college. (The article was correct that he paid his own way through Harvard, however.)

But why was this student in Boston even mentioned in the Atlanta paper of record?

» RELATED | W.E.B. Du Bois: An overlooked intellectual and civil rights warrior

» MORE | The Niagara Movement: A 'mighty current' of Negro activism

At that time, The Atlanta Constitution had very contradictory ways of covering race. News fronts screamed with headlines of alleged black criminals and descriptions of lynchings. But interspersed among those race-baiting reports were happier tales of elite African-Americans who made good, especially if those overachievers had Southern ties and gracious manners.

The 1890 Constitution article had a career path in mind for Du Bois, proclaiming that the Harvard phenom “will study law, and put out his shingle somewhere south of Mason and Dixon’s line.” Du Bois never got that law degree but in 1895 he did become the first African-American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard — in sociology.

Atlanta University hired Du Bois in 1897 to create the school’s sociology department and the Constitution often reported on his activities and speaking engagements while he remained an Atlantan.

For instance, in 1898, the paper lauded Du Bois for a study about black life in Farmville, Va. And in that same year, it noted that he was elected president of the American Negro Academy.

Du Bois' accomplishments also appeared in a weekly newspaper column penned by Henry Rutherford Butler called "What the Negro is Doing: Matters of Interest Among the Colored People." Butler, a black physician and pharmacist, wrote the general interest column for the Constitution between 1895-1904.

Butler’s first mention of Du Bois was in the 1896 announcement that Atlanta University would create a new sociology school and was looking for someone to lead it. Butler may have been giving Du Bois a nudge in the hiring process when he referred to another school being lucky to secure his services.

The Constitution’s coverage of Du Bois could also turn prickly, if not downright hostile.

In 1902, the paper’s editorial board was quick to pounce when Du Bois became a vocal critic of the South. One editorial from Jan. 26 sarcastically titled “A diagnosis by Du Bois” stated, “His friends in the north are his friends only so long as he remains in the south and makes himself the instrument of their evil feelings towards the white people of this section.”

Later that year, Du Bois wrote an article for The Atlantic magazine that criticized the South's lack of racial equality. And although he didn't mention Booker T. Washington by name, Du Bois attacked his position by stating that blacks should be trained for more than just manual labor.

» MORE | How 'Atlanta Compromise' divided black America

» GALLERY | The W.E.B. Du Bois photo collection: Atlanta and Georgia scenes

Again, the Constitution editorial board excoriated Du Bois in two bitter editorials titled “A Negro False Prophet and His Dangerous Lesson.” Both editorials expressed a preference for Washington’s vision, with one saying, “We trust Du Bois is so isolated an exception that his conduct does not call in question the wisdom of a collegiate education for the negro.”

The paper soon returned to a routine of reporting on his accomplishments, whether in Atlanta or out. And it’s fair to note that over Du Bois’ 70-year career, the Constitution eventually became an advocate for racial equality too.

Du Bois left Atlanta in 1910 for the New York offices of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People – a group he co-founded the year before. He returned to Atlanta between 1934-44 for a second round of chairing the sociology department at Atlanta University.

Du Bois died in 1963 at the age of 95, one day before the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. By that time, he had become a Communist and lived in exile in Ghana.

In 1965, The Atlantic magazine published his words one last time, in the form of an interview he gave a few months before his death. The interviewer? Atlanta Constitution editor and publisher Ralph McGill.

ABOUT DEJA NEWS

In this highly irregular series, we scour the AJC archives for the most interesting news from days gone by, show you the original front page and update the story.

If you have a story you'd like researched and featured in AJC Deja News, send an email with as much information as you know. Email: malbright@ajc.com. Use the subject line "AJC Deja News."

» AJC HISTORY AT YOUR FINGERTIPS: AJCreprints.com | Photo reprints | Content archives