Ralph David Abernathy, civil rights leader, King's friend, dies

The Rev. Ralph David Abernathy's death came 22 years and 13 days after the slaying of the man to whom he devoted his life.

An official statement from Crawford Long Hospital said his heart stopped at 12:10 p.m. Tuesday night. Spokesman Mendal Bouknight said the exact cause of death probably would not be determined until today. "We are working with the family at this time, trying to follow their wishes on privacy," he said.

The Rev. Abernathy had been in the hospital since March 23, suffering from a sodium imbalance.

He suffered a stroke in January 1983, had a bypass operation for a blocked cerebral artery in March 1983, and suffered an apparent second stroke in June 1986.

"I think he'd like to be remembered as a man of God first, a man of peace and a man of love," his 31-year-old son, Ralph David Abernathy III, said Tuesday night. He said his father's tombstone will bear the simple inscription:

"I tried."

"That was his choice," he said. "That was more or less his motto."

The Rev. Abernathy was senior pastor of Atlanta's West Hunter Street Baptist Church and had been a minister of the church since 1961.

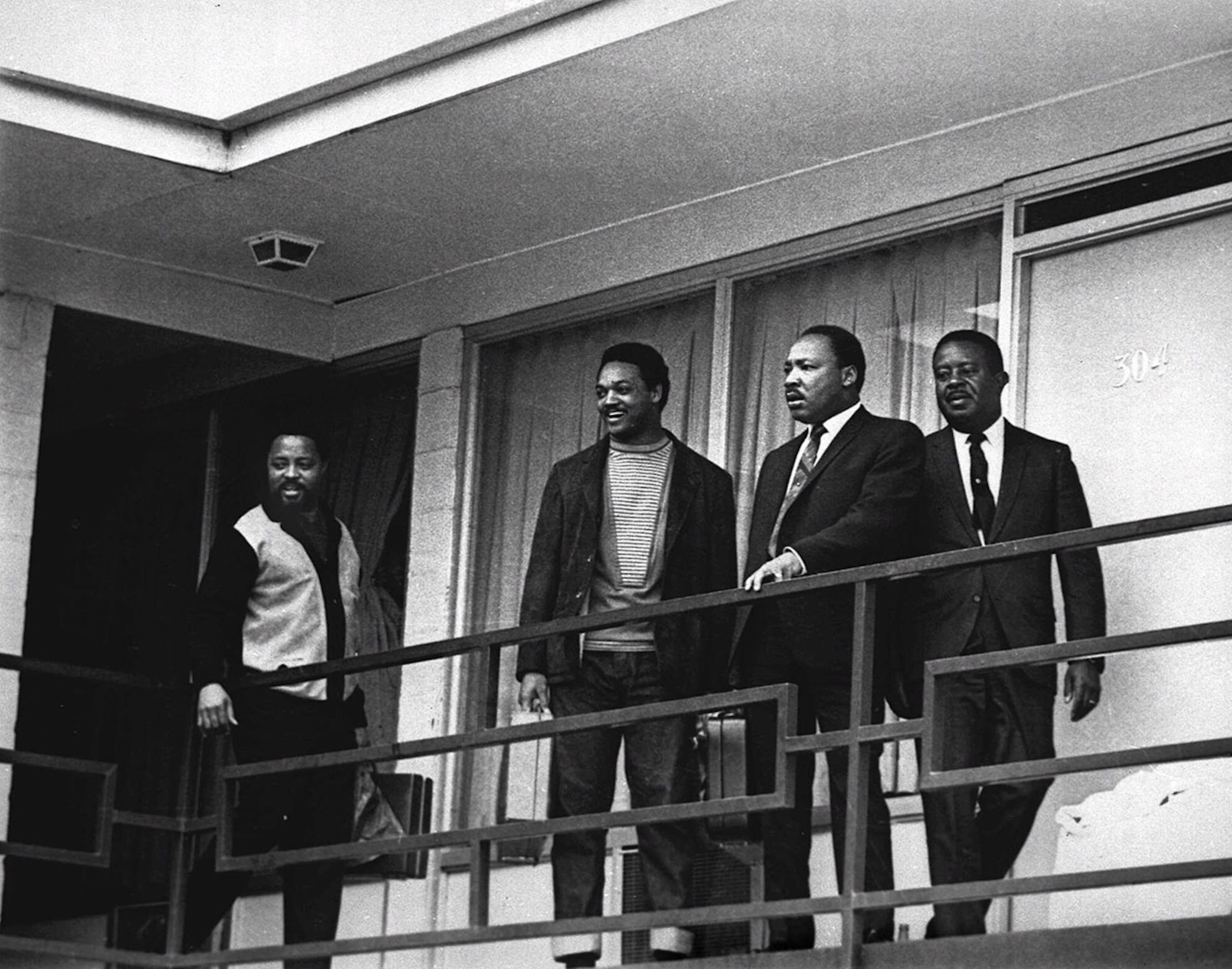

For 13 turbulent years, from December 1955 until Dr. King's assassination in April 1968, the Rev. Abernathy was constantly at his side during the civil rights revolution. The two were inseparable, "like Damon and Pythias," recalled the Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker, former Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) executive director.

"Ralph is the best friend that I have in this world," Dr. King said in 1968 just before his death.

As two militant Montgomery, Ala., preachers, they led a successful yearlong boycott of the city's bus line, eventually ending Alabama bus segregation. Their organization, the Montgomery Improvement Association, was the forerunner of the Atlanta-based SCLC, which they also led. The SCLC spearheaded the U.S. civil rights movement, helping bring about passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and the striking down of Jim Crow segregation laws in Southern states.

The Rev. Abernathy and Dr. King were jailed together 17 times. The Rev. Abernathy was in a nearby cell when Dr. King wrote the historic "Letter from the Birmingham Jail" in 1963, setting forth the goals of the movement. Later that year, the Rev. Abernathy was at Dr. King's side for his "I Have a Dream" speech in front of the Lincoln Memorial, climaxing the march on Washington, D.C.

The Rev. Abernathy was a few feet away when Dr. King was shot down in Memphis in 1968.

They were profoundly different in their upbringing and educational backgrounds. Dr. King was the son of a well-to-do Atlanta minister and a graduate of Boston University and Crozer Theological Seminary. The Rev. Abernathy was the son of a rural Alabama farmer and a product of Alabama State College in Montgomery.

He lacked Dr. King's charisma, educational background and oratorical skills. They came to be known as "Mr. Rough and Mr. Smooth" during the Montgomery bus boycott.

The relationship was defined in that period. During a minor dispute in a meeting of the Montgomery Improvement Association board of directors, the board sided with the Rev. Abernathy against Dr. King. The latter became physically ill and went home. Later, he exacted a promise from the Rev. Abernathy never to disagree with him in public again.

The Rev. Abernathy did not question his secondary role, and he idolized Dr. King, finding a biblical parallel for their relationship: He was Aaron to Dr. King's Moses.

He was Dr. King's alter ego, a sounding board for his innermost thoughts and fears, and he warmed up their audiences.

"When Ralph plants himself behind the lectern, squat and powerful, his round face breaking easily into laughter, his listeners both love and believe him," Dr. King said.

In January 1957, the Rev. Abernathy's Montgomery home was bombed, a year after Dr. King's home suffered the same fate. The Rev. Abernathy was in Atlanta, visiting Dr. King.

His wife and daughter were sleeping in a back bedroom and escaped harm.

The movement swept Dr. King and the Rev. Abernathy along on a fateful odyssey - to Atlanta, Albany, Birmingham, Washington, St. Augustine, Selma, Chicago, Memphis.

When a rifle bullet tore into Dr. King's body, the Rev. Abernathy had just stepped back into their room at the Lorraine Motel to splash cologne on his face. He ran to Dr. King, kneeling and cradling him in his arms while others went for help.

'I never had any desire to lead'

Three years before his death, Dr. King chose the Rev. Abernathy as his successor as SCLC president. "I can think of no man who is closer to me," he said.

The Rev. Abernathy reluctantly accepted. "I never had any desire to lead the movement," he said. "I always wanted to stand with him, and not ahead of him."

In 1968 he led the "Poor People's Campaign," conceived by him and Dr. King in the Birmingham jail. Thousands marched on Washington to dramatize the plight of the poor. Dressed in overalls - a trademark of the Rev. Abernathy in civil rights marches - they erected "Resurrection City," a shantytown. He was jailed for refusing to comply with police efforts to tear it down. The next year, he led demonstrations in support of striking hospital workers in Charleston, S.C.

But the movement had peaked. Afterwards, SCLC lost its place as the premier civil rights group. Andrew Young left to run for Congress from Atlanta; years later he became Atlanta's mayor. Jesse Jackson left the SCLC and led "Operation Breadbasket" and People United to Save Humanity, or PUSH, in Chicago.

SCLC had to compete for funds with the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, which had been created in Atlanta by Dr. King's widow, Coretta. "I was in no position to fight her," the Rev. Abernathy said.

In 1973, he resigned as SCLC president, but associates persuaded him to stay. He quit again in 1977, this time for good. He entered politics. He got only 3,614 votes in a losing effort to replace Mr. Young, who had resigned his congressional seat to become U.N. ambassador. The Rev. Abernathy finished third behind Wyche Fowler and John Lewis.

"People have said the fault with my leadership is that Martin Luther King had a Ralph Abernathy but Ralph Abernathy had no one like me," he said.

The Rev. Abernathy stunned Democrats in 1980 when he endorsed Ronald Reagan for president. Georgian Jimmy Carter "just didn't produce" as president, the Rev. Abernathy said. "We've got to move on." He said Mr. Reagan could revive the economy and provide jobs for blacks. In 1984, the Rev. Abernathy endorsed Jesse Jackson for president.

The Rev. Abernathy suffered a major snub in 1986. He was excluded from a planning group for the first Martin Luther King Jr. national holiday.

Autobiography

The Rev. Abernathy's massive, 638-page autobiography, "And the Walls Came Tumbling Down," was published by Harper & Row in 1989, setting off a storm of protest.

He made frank allegations about Dr. King, who he said had romantic liaisons with two women the night before his death and struck or shoved a third woman the next morning. The woman was angry because Dr. King had spurned her, according to the Rev. Abernathy. Dr. King often used him to straighten out quarrels growing out of extramarital affairs, the Rev. Abernathy wrote.

Helped affirm freedom of the press

The Rev. Abernathy unwittingly aided freedom of the press in 1960. His name and those of 18 other black ministers were carried on a full- page New York Times ad placed by the Committee to Defend Martin Luther King, then facing perjury charges in Alabama. The ad reviewed alleged violations of constitutional rights by officials including Montgomery police. The writer, Bayard Rustin, never asked the ministers' permission. Montgomery Police Commissioner L.B. Sullivan sued the Times, the Rev. Abernathy and three other Alabama ministers for libel.

The suit, Sullivan v. New York Times, and other suits filed by Alabamians were intended to intimidate civil rights leaders and newspapers, according to New York Times official Harrison E. Salisbury.

An Alabama jury awarded Mr. Sullivan $500,000 in damages. The Rev. Abernathy's car, bringing $400 at auction, and some land he inherited, bringing $4,350, were seized. He considered moving North to escape further seizures of his assets.

In a historic 1964 decision, the Supreme Court reversed the verdict, ruling that public officials cannot recover damages unless they prove malice, a decision considered one of the most important in U.S. history upholding First Amendment protection.

West Hunter Street Baptist Church

At Dr. King's urging, the Rev. Abernathy followed him by a year to Atlanta, becoming pastor of West Hunter Street Baptist Church in 1961. West Hunter Street was renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Drive after Dr. King's death in 1968. The Rev. Abernathy's church moved to 1040 Gordon St. in 1973 but kept the name.

His church received a federal grant and built the 100-unit, $6 million Ralph David Abernathy Towers on Oglethorpe Street, which opened in 1985. It houses elderly and handicapped people.

Youth, Army and entering the ministry

The grandson of slaves, David Abernathy was born March 11, 1926, in Linden, Ala., a town of 2,773 in Marengo County. He was the 10th of 12 children of William L. Abernathy, a farmer and deacon, and Louiverny Valentine Abernathy.

The name "David" is on his birth certificate, he wrote in his autobiography. However, a sister, Manerva, admired a teacher at her school, Ralph David, and began calling her brother by that name. He registered for the Army by that name and always used it thereafter.

His father, Will Abernathy, grew 100 to 150 bales of cotton annually on 500 acres and also owned cattle, hogs and chickens. He died when Ralph David was 16.

The young Mr. Abernathy was drafted in 1944. He joined an all-black unit with white officers and became a platoon sergeant. They reached Europe near the end of World War II and "were trucked from one city to another" in France and Germany as replacements.

After his discharge, he passed a high school equivalency test and enrolled at Alabama State College in Montgomery in September 1945. There he became student body and class president. He led successful student protests of bad food in the dining hall and poor living conditions for men in barracks; the school was forced to make improvements. While a student, he announced his call to the ministry, a career he had envisioned since his upbringing in a devout Baptist family.

For a year, he attended graduate school at Atlanta University. While here, he met Dr. King after hearing him preach at Ebenezer Baptist Church.

For a brief period, the Rev. Abernathy was dean of Alabama State and part-time pastor of a church in Demopolis, Ala. In 1948, he was named pastor of Montgomery's black First Baptist Church. Alabama State awarded him a diploma in 1950.

Prelude to the movement

Dr. King was named pastor of Montgomery's Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in 1954. A close friendship began. They and their wives, Coretta and Juanita, dined together often. The Supreme Court had outlawed school segregation that year in its Brown decision. In nightly sessions, the two young ministers planned how they would turn Montgomery into "a model of social justice," the Rev. Abernathy wrote.

But Dr. King was planning to take three years to establish himself in Montgomery, and the Rev. Abernathy had decided to return to school and get "the same kind of academic credibility" his friend had. Those plans were changed abruptly when they were thrust into leadership roles in the bus boycott.

The Rev. Abernathy addressed the United Nations in 1971. He received an honorary doctorate from his alma mater, Alabama State. At various times, he was president of the World Peace Council, a member of the board of directors of the King Center, and chairman of the Southern Christian Leadership Foundation.

He also belonged to the NAACP, the Urban League, the Council of Christians and Jews, the YMCA, the Atlanta Baptist Ministers Conference, the National Black Political Assembly, the Anti-Defamation League, the Baptist World Alliance, the World Council of Churches, the Masons, the Elks, Alpha Kappa Mu, Alpha Kappa Delta and Kappa Alpha Psi.

A son, Ralph David Abernathy III of Atlanta, represents District 39, part of Fulton County, in the state House of Representatives.

Surviving the Rev. Abernathy in addition are his wife, Juanita Jones Abernathy; another son, Kwame L. Abernathy of Atlanta; two daughters, Juandalynn Abernathy of Konstanz, West Germany, and Donzaleigh Bosley of Atlanta; five brothers, Jack Abernathy of Birmingham, Garien Abernathy of Cleveland, James Abernathy of Los Angeles, and Clarence and William Abernathy, both of Linden; and four sisters, Lula Yarbrough of Cleveland, Louvenia Coats of Birmingham, and Manerva Lawson and Susie Hildreth, both of Linden.