While in the fourth grade in Greensboro, N.C., waiting her turn in the school lunch line, a white classmate of Connie Curry called one of the servers behind the counter a racial slur. Connie’s response was startling as a sunbeam.

“This woman,” she told the boy, “is just as good as your mother. And you don’t talk about mothers in the South that way.”

During recess the boy responded by shoving Connie into a puddle, leaving her brand new brown-and-yellow raincoat oozing with mud. It foreshadowed the years she would spend toiling in the trenches of the civil rights movement.

More than seven decades later, she is part of the mural on the Freedom Trail in Atlanta where it crosses the Atlanta Beltline. Curry is placed center-top among the collage of images entitled “Journey to Freedom: Women of the Civil Rights Movement.” Hers is the only white face.

Connie’s half sister Ann Curry recently found among the activist’s personal papers an American Civil Liberties Union pamphlet entitled “Know You’re Rights,” a primer for young black men on how to react when stopped or arrested by police. This was published in 1966, well over a half-century before the world knew about George Floyd.

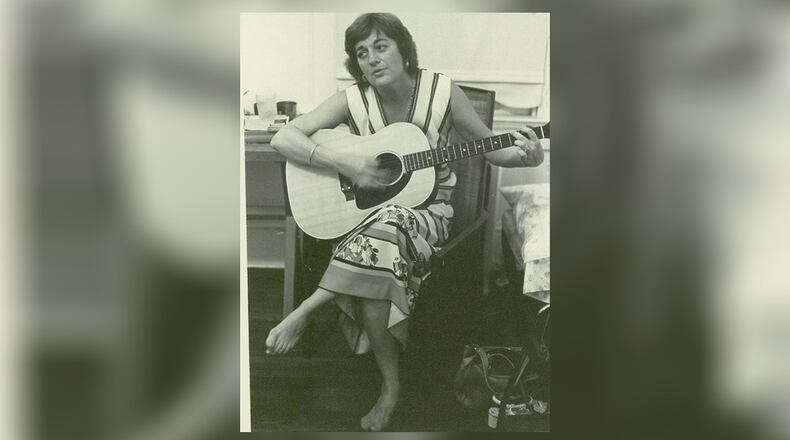

Constance Curry, 86, an activist, historian and author and editor of five books died June 20 of complications from sepsis. A service will be delayed because of the cornoavirus.

She was born July 19, 1933, in New Jersey, her family moving to Greensboro when she was in the third grade. In an oral history given to the Atlanta History Center in 2005 Curry points out that she and older sister Eileen were “not raised with the typical Southern white something … well, prejudice.”

Her parents had left Ireland to escape that country’s bigotry, her father Ernest arriving at Ellis Island in 1925.

Curry went to Agnes Scott College, all-white school that, in her words, “wasn’t particularly liberal.” But she became absorbed in racial issues, joined the National Student Association and made friends among the region’s historically black colleges and universities.

“I began realizing (the movement) was not only religious, intellectual and historical … But it affected my life personally. I couldn’t eat with my [Black] friends [after meetings]. Once you start taking things personally, the passion is enhanced.”

In 1960, she was named the first director of the NSA’s Southern Student Human Relations Project, which opened an Atlanta office. She became an adult advisor to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Curry quickly discovered that civil rights activism wasn’t always compatible with a mainstream Atlanta social life, circa 1960. She and three other women shared an apartment on Adair Avenue in Virginia Highland and were delivered an eviction notice.

“Drinking, noise and association with colored men on a social basis are not allowed in this building or on these grounds,” the notice said. “Do not have negroes here! Have the apartment vacant by Thursday evening 6 p.m.”

From 1964 to 1975, she was a field representative for the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker organization. She traveled the South securing grant money for black families to get jobs and food. But her major assignment was investigating reports of intimidation and reprisals against black families attempting to desegregate schools under Civil Right Act of 1964.

In that role she met and grew close to the family of Mae Bertha Carter and her husband Matthew in Mississippi, who fought to get their children into white schools.

When Curry left the AFSC she became Atlanta’s director of human services from 1975-90, first under Maynard Jackson and later Andrew Young. Nancy Boxill, who spent 25 years on the Fulton County Commission, said recently, “Connie basically invented that office. It was basically up to Connie to figure out what people needed, like housing, health care, public safety, food or whatever, and then figuring out how to get it to them.”

Curry wrote she “had a long string of crushes, flings, and trysts,” but she never married. This essentially met she never stopped fighting injustice according to Benetta Standly, a Public Policy Director for Georgia’s ACLU, and a close friend for the last 15 years.

Standly said that many of Curry’s concerns remained those she’d been involved with much of life: reducing the school to prison pipeline, eliminating disproportionate discipline issued to African Americans students, abolishing the death penalty and securing the right to vote for prisoners. She also, incidentally, graduated from law school at age 50 but seldom practiced except to help get people out of jail.

Judging from her oral histories and writings, perhaps her warmest, and most bittersweet, memory was a brief conversation with Martin Luther King in April 1968, the night prior to his leaving for Memphis where he was assassinated.

“He was having a meeting in the basement of Ebenezer Church,” she said. “I went up to him … He was talking to somebody, shaking hands on right side and I came up on the left side and he put out his hand to me. He said, ‘excuse my left hand Connie, but you know, it is the one closest to my heart.’

“Those,” she said, “were the last words I ever heard from Dr. King.”

Connie Curry is survived by her sister Ann Curry (Enoch Hendry), her nephews, Coran Hendry and Walker Hendry (Sara Jane Fogarty), and her stepbrothers, Ian Holloway (Debbie) and William Holloway.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured