In 1967, the Rev. Austin Ford, an Episcopal priest, moved into a run-down, two-story house in the Peoplestown area.

He was a strange sight at first. The white man in his late 30s rode his bicycle through the predominantly black community and knocked on doors to talk to residents about ways they could work together to improve the area.

The polished but affable Ford, who grew up DeKalb County, moved into what is now Emmaus House, an Episcopal Church mission, with the aid of at least two nuns and a seminary student.

“He didn’t just drop in,” said longtime Peoplestown resident Columbus Ward. “He moved in. He became a neighbor. He made it known that this Southern white man had no problem fighting the system.”

And that he did, even at times if it meant butting heads with city powers-that-be and even some diocesan authorities.

Ford, of Grant Park, a tireless advocate for Atlanta’s disenfranchised and poor, died Saturday at 89.

Ford will be cremated and a time for a memorial service is yet to be determined. A.S. Turner & Sons Funeral Home and Crematory in Decatur is in charge of arrangements.

Ford served as executive director of Emmaus House, started on the corner of Capitol and Haygood avenues, for roughly three decades.

“Austin Ford was someone who believed and lived his faith shoulder to shoulder with people from all situations and circumstances,” Robert C. Wright, the bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Atlanta, said in a statement. “He was a man and a priest who understood that Jesus wants His followers with the poor. His shoes will be hard to fill. His example changed minds, hearts and lives.

Related: For decades, this Episcopal priest has lived and worked among the inner city poor

The house was a wreck when Ford, who was the rector at St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church, arrived.

In a 2011 interview with LeeAnn Lands for the Peoplestown Project, Ford describes the place that would become a center for change in the community.

“The place was a terrible wreck. It had been a sort of flophouse for alcoholics. There were signs on the doors saying, ‘Two dollars a night’ and things like that. And I remember Sister Mary Joseph — later she became Sister Mary Rose — [chuckles] she had to have a cigar to clean out the place, there was such an awful smell. Anyway, we all went there, and then there was a Moravian seminary student who came. So the four of us went there, moved in and just waited to see what would happen.”

The nation was still going through the turbulent civil rights movement. In the year after Ford moved into Emmaus House, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis and the the Poor People’s March was held in Washington.

Ward, who got involved as a teen, eventually joined Ford at Emmaus House, working there for 36 years, before retiring as assistant director in 2008.

He said it was important that Ford didn’t come in and tell residents what to do. He wanted them to be part of the change.

Ford set up an after-school program at Emmaus House, once-a-month transportation to the state prison for families of inmates, chapel services, hot meals, and a poverty rights office. He led efforts for welfare rights, neighborhood empowerment and racial justice, according to the Emmaus House website.

His social justice work, though, began earlier. Ford was involved in the movements to integrate schools, end housing discrimination and register people to vote. His work earned him critics as well as supporters among local residents and the city’s elite.

His commitment to civil rights, according to an article in the Emory University Magazine, began two years after he graduated from Emory with a bachelor’s degree in English and Greek.

“In the summer of 1952, before his last year at the divinity school of The University of the South, the school’s trustees voted to reject the first African-American applicant to the seminary. In the ensuing chaos, nine faculty members and half the students left, and many of those who remained, including Ford, were stirred to protest,” according to the article.

“We were all in a way radicalized and motivated to do something about a segregated society,” Ford says in the interview. The school eventually reversed its ruling, but the incident left a mark on Ford.

The Rev. Ricardo Bailey, vicar of the Episcopal Chapel at Emmaus House and head chaplain at Holy Innocents’ Episcopal School in Sandy Springs, worked with him for several years.

“What drove him was a fundamental call of seriousness that he took from Jesus of Nazareth to radically love your neighbor as you love yourself,” Bailey said.

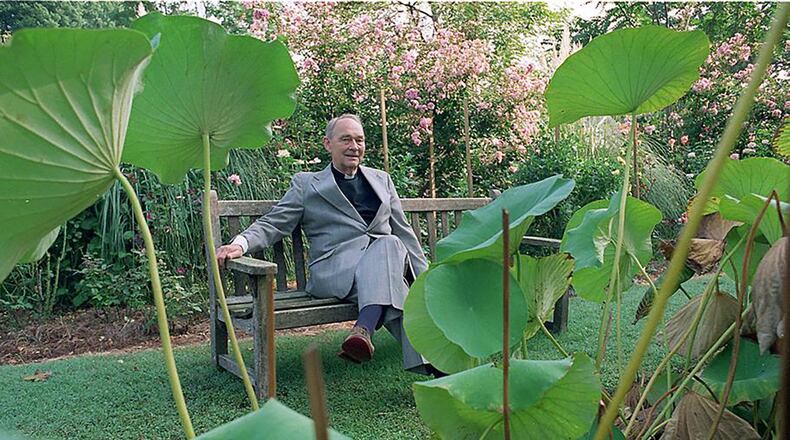

Ford had a passion for gardening and brought many of his antiques and fine furniture into the Emmaus House and the chapel, said Bailey. He also kept a beautiful garden at his Grant Park home, said a cousin, Nancy Olive Dougherty, of Carrollton. “He worked on that all of the time,” she said.

“He really wanted the people at Emmaus House, especially at the chapel, not to feel like they were second-class Episcopalians,” said Bailey. He wanted people to feel that ” they were just as important as anybody else in any other parish.”

His legacy , said Ward, is to let people know that things “can get better in this country, this city and this neighborhood. You need hope to do that. He made the neighborhood better.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured