Rape kit backlog yields new leads in metro Atlanta cold cases

Twenty years after she was raped in a garage at the age of 16, one Georgia woman will finally see her alleged attacker face charges in court.

It could be among the first sexual assault cold cases to be solved using DNA evidence from thousands of previously unsubmitted rape kits in the state.

A newly-formed Metro Atlanta Sexual Assault Cold Case Task Force seeks to break these old cases using new leads that are emerging as the Georgia Bureau of Investigation works its way through its backlog of evidence amid a national movement to reform how society and the legal system treat sexual assault. The task force includes law enforcement from Cobb and Dekalb counties, and the city of Atlanta.

“It’s an opportunity for us to serve victims and to get them the resolution and the justice they deserve,” said Christie Nerbonne, a criminal investigator with the Cobb County District Attorney’s Office assigned to the task force.

While law enforcement officials say they are focused on serving justice now rather than dwelling on the past, the 20-year-old case demonstrates what some consider decades of failure by authorities to take sexual assault seriously. By the time he was charged with rape in Cobb, the suspect had accrued an extensive criminal record including armed robbery, drug possession and child neglect.

The victim in the case declined to be interviewed for this article as the case heads toward a trial.

Natasha Alexenko, who became an advocate following her own violent assault in 1993, said there is a lot of anger and sadness among sexual assault survivors, some of whom have seen the statute of limitations expire as critical evidence sat on shelves.

Alexenko said she spent years blaming herself as a “bad witness” for the fact that her rapist remained at large. She had no idea that her rape kit had never been processed.

“Our body is a crime scene,” she said, describing the invasive two-hour forensic medical exam. “You go in for evidence collection and you have to recount all the horrific details to a complete stranger … and to have those rape kits sit and languish, it’s so unjust.”

Finally, in 2003, the DNA from Alexenko’s kit was indicted, and in 2007 it was matched to the perpetrator who was eventually convicted.

There are myriad reasons that contributed to the national rape kit backlog, experts say.

When the Georgia Bureau of Investigation began DNA testing in the early nineties, law enforcement lacked clear protocols, and processing samples was considered too costly to do in all cases. At first, there was no database against which to compare samples. Sometimes, victims declined to cooperate in pressing charges.

In the case of the 16-year-old who was raped in Cobb, she only knew the perpetrator by a nickname and police were unable to track him down. It was common practice among local law enforcement at the time to submit rape kits to GBI only when there was a suspect to test against.

In 1998, GBI implemented the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s DNA database, known as CODIS. But state law only required samples from individuals convicted of certain sex crimes. Later, the law was expanded to include most incarcerated felons, but only “to the extent funds are appropriated or available.”

“While it was on the books, it wasn’t necessarily being done,” said Theresa Schiefer, a Cobb prosecutor on the task force.

It wasn’t until 2011 that a mechanism was written into the law for collection of DNA from all felons.

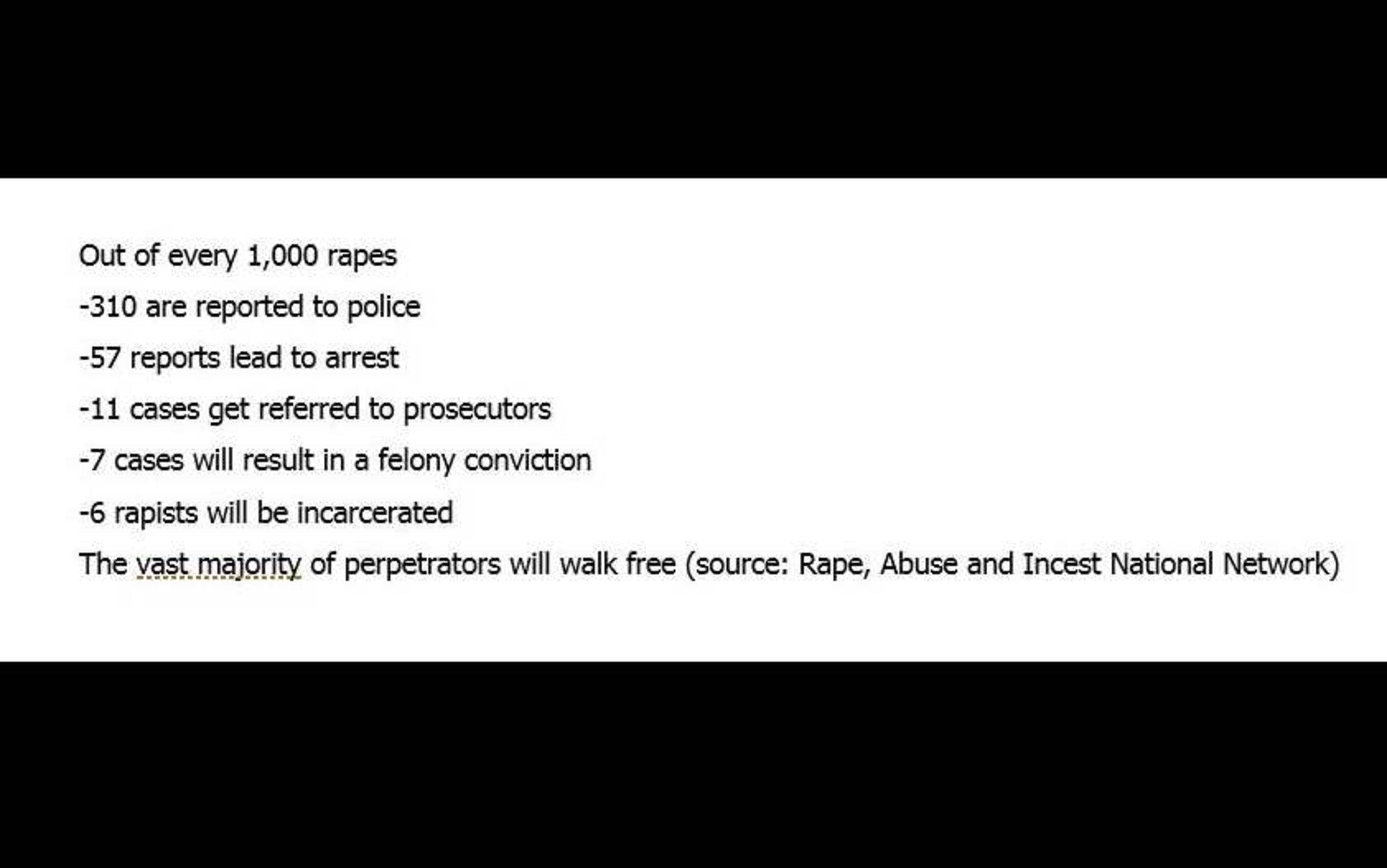

In the years since, public pressure has yielded legislative reform and increased funding to address the backlog of unsubmitted kits—more than 100,000 nationally, according to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network.

In 2016, Georgia passed a law requiring all stored rape kits be submitted to GBI for testing. By April of this year, the state agency announced it had reduced its backlog by two-thirds.

Schiefer also credited progress to advances in criminal profiling and research on how trauma can affect victims and witnesses.

“We can’t change the past,” Schiefer said. “We just have to move forward.”

Schiefer said Cobb alone has submitted hundreds of previously untested rape kits, some of which are turning up new DNA leads. In those cases, she said, she and Nerbonne are pulling old reports and reopening investigations—carefully.

“Some of these survivors, they may not have even told anybody that this happened, especially the ones from the nineties to the early 2000s,” Nerbonne said. “We’ve got to be really careful in how we approach it and how we make contact with people.”

Alexenko said there is still much work to be done until all rape kits, new and old, are processed, tracked and victims notified.

“There are too many people that will never have the justice I received because their kits languished for too long,” she said. “It’s impossible to sleep at night knowing that there’s still people out there who are struggling.”