Two years ago, student journalists with the Georgia News Lab asked the Cobb County Sheriff’s Office for the agency’s use of force policy, a public record readily available in every law enforcement agency’s operations manual. Cobb fulfilled the request — 54 days later.

This year, News Lab repeated the exercise. Same request. Same policy. But Cobb sent the document the same day it received the request.

The office took deliberate steps to improve following the poor performance cited in the News Lab story from 2016, according to Cmdr. Robert Quigley.

“The sheriff made it very clear to the staff that we were going to do everything we could to meet the terms of open records (laws),” Quigley said.

The public depends on the state's sunshine laws to obtain information about the functioning of government and the performance of public officials. To test compliance with the law, in 2016 and again this year, the News Lab sent requests for routine public records to more than 140 local agencies and law enforcement offices in 13 metro counties. Law enforcement received a request for use of force policies, while governments received one for payroll records.

The investigations found that nearly half of the agencies tested provided records faster than in 2016 — in some cases by weeks. But nearly a third of the agencies failed to meet the law’s requirement that they acknowledge a request within three business days and provide the records, or tell the requester when they will be available. The law requires agencies to promptly provide records that are readily available.

News Lab journalists also encountered problems with how agencies responded to requests, from inappropriate demands for fees to staff who were unfamiliar with what the law requires.

“This is definitely an indication about how much work there is to do,” said Georgia First Amendment Foundation President Richard T. Griffiths. “Cities and counties in Georgia have to do more about responding to requests from the public.”

Atlanta adopts new procedures

Georgia's sunshine laws made news this year after the AJC and Channel 2 Action News reported that senior officials in the administration of former Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed frustrated requests for public records, prompting the Georgia Office of Attorney General to open the first-ever criminal investigation into violations of the open records act.

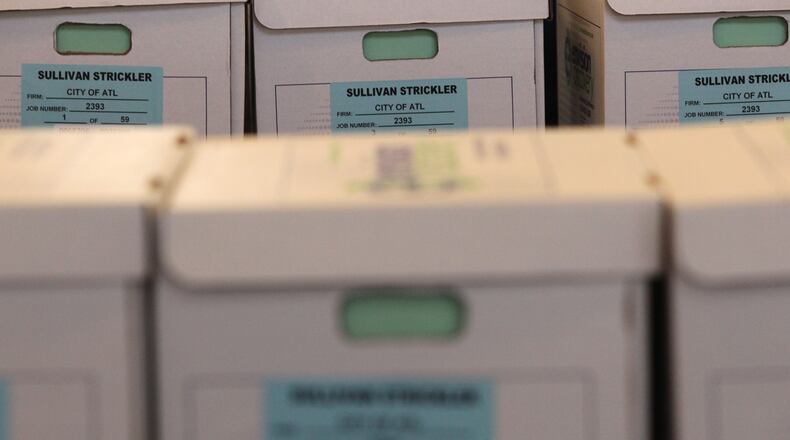

The administration of Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms enacted new compliance measures in response to a separate civil compliant the news organizations filed with the attorney general, which accused the city of systematic violations of open records law.

Atlanta’s response times improved dramatically in 2018 under the new Bottoms administration.

In 2016, the Atlanta Police Department’s open records division took 50 business days to provide its use of force policy.

This year, the department provided the document in six days — but not without difficulty. It first sent a link to a website where all the department’s policies are posted. After a reporter sought clarification, the department sent the document along with details of where it was on the website.

The city’s response to a request for payroll records also improved. In 2016, the city took 54 days to provide the records. This year, the city provided the record in four days — but with one hiccup. Three business days after submitting the request, a reporter received a call from press secretary Michael Smith asking what the information would be used for.

Carolyn Carlson, a retired communications professor from Kennesaw State University who trained public officials on complying with the state’s sunshine laws, said it is not appropriate for agencies to ask why requesters want records.

“It is none of their business,” Carlson said. “If it is a public record, you have a right to it no matter why you want it.”

Atlanta’s proposed procedure for handling records requests from the media and the public will remove the mayor’s press office from the process and place it under an independent transparency officer.

Other agencies improve

Many other agencies also provided records more quickly this year. In 2016, 17 agencies took more than 20 days to provide requested records or never produced them at all, compared to 13 agencies this year.

The DeKalb County Sheriff’s Office sent records after three days but sent them by postal mail rather than emailing electronic copies as requested. In 2016, it took the office 54 days.

Stone Mountain police and the city’s government provided records within three days that took the two agencies 46 and 19 days to provide in 2016.

In 2016, the Henry County Police Department sent its use of force policy in less than an hour and a half. This year, it provided the policy just 10 minutes after the request went out — the fastest response of either year.

“We are a … believer in open records,” said Henry Police Capt. Joey Smith. “It’s just a law we try to abide.”

More than a quarter of the agencies took longer to provide records this year. More than half of the agencies provided compliant responses both years.

Problems remain

Human error, technical failings and a poor understanding of what the open records law requires were often at the root of an agency’s failure to comply with the law in a timely manner.

College Park police and the city government complied with requests in one day in 2016 but took 18 and 31 days respectively to do so this year. Reporters learned the city clerk, who handles requests for both the city and the police, left her position the day the requests were submitted and the new clerk said she did not receive the requests or follow up messages left with her predecessor.

Austell originally provided a cost estimate of $120 for its payroll records, including $100 for “attorney fees.” The city clerk told a reporter the fee covered time the city attorney spent determining if the records could be released.

When the reporter informed the clerk that state law does not allow such charges, the clerk replied that she was "not aware" of that provision and lowered the fee to $20.

Carlson said that many errors in handling requests are the result of a poor understanding of the law. “It shows a lack of training mostly, I would say, for the people who are in charge of the records,” she said. “They don’t understand (the law), or haven’t been trained well enough.”

Technical problems were also an issue.

Requests emailed to Fulton County and its sheriff’s office were entered into a new online system.

When the system showed the request for payroll records was still “processing” after nearly two weeks, a reporter emailed the designated records officer. She received an automated reply saying the officer’s response times would be “rather delayed” because she would be “spreading Employee Engagement Cheer throughout Fulton County” during Fulton County Employee Appreciation Week.

In response to a request emailed to the Fulton County Sheriff’s Office, a reporter received a response after six business days that the requested document was ready for downloading but she was unable to access the online system. She only gained access three weeks later, after calling the sheriff’s office records custodian who created an account for her.

The East Point city clerk did not respond to records requests for more than a week. In response to follow up messages, the clerk’s office explained that the clerk had been on vacation and had not received the requests.

The office sent the police department’s use of force policy a week later.

For payroll records, the clerk’s office sought copying charges of $6.70. They indicated they would not accept personal checks and that prepayment was required.

A reporter reminded them that the request was for electronic records and that the law does not require agencies to demand prepayment if estimated fees are less than $500.

The clerk sent the records four days later without charge.

She later wrote that the city changed its policy on Nov. 1, and no longer charges for electronic records.

Metro Atlanta’s newest city canceled a request — without providing records.

In response to a request for payroll records to the city of South Fulton, the records administrator provided a fee estimate of over $57. After a reporter reminded the administrator that she requested the records in electronic form, the administrator responded that the document was ready at a cost of $28.85 for one hour’s work.

The reporter made multiple requests for clarification of the work involved in processing the requests and whether the records would be provided as an electronic spreadsheet, as requested.

Without clarifying, the administrator eventually sent a message stating that the request would be "closed out" if the reporter did not sign a statement accepting the charges.

A week later, the reporter received notification that “your request has been closed.”

“That’s not the procedure they should be following,” said Carolyn Carlson, a retired Kennesaw State University communications professor and expert in government transparency. “To suddenly dismiss the request instead of answering your questions is not right.”

— Jade Abdul-Malik

Tips from News Lab journalists

When you make your request cite the law. — Erin Valle

Always leave a paper trail. — Jade Abdul-Malik

Ask how much it’s going to cost in advance. — Mauli Desai

Be as specific as possible in your request. — Ashley Soriano

Be aggressive in following up on your request. Don’t be afraid to be annoying. — Justine Lookenott

Know who to talk to when you don’t get what you want. — Bianca Theodore

Ask for an explanation when you haven’t received your records. — Kaley Lefevre

Talk to the attorney general’s office if agencies are not being cooperative. — Anila Yoganathan

Be nice and cooperative. That’s your best bet in getting records. — Erin Schilling

Do your research before your request so you know what to ask for. — Tucker Toole

People are more responsive over the phone or talking to them in person. — Sabrina Kerns

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured