Mayor Kasim Reed saddled with world-class headache over Braves’ move

Staff photographer Curtis Compton contributed to this report.

A history of Turner Field

- Monday The Atlanta Braves announce the team's intention to move to a Cobb County stadium.

- Thursday. Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed is informed that the Braves plan to move to Cobb County.

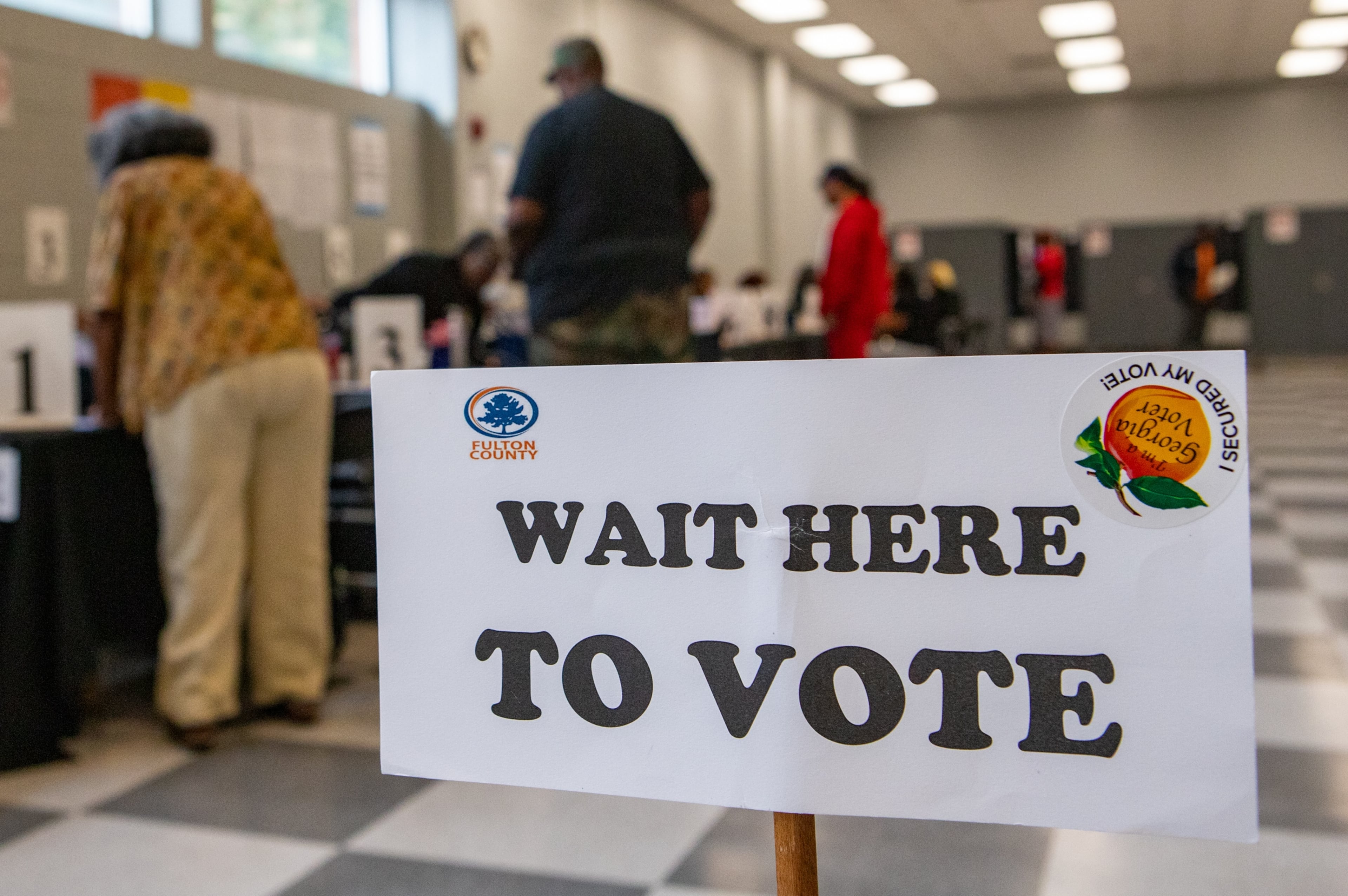

- July. The Braves and the city of Atlanta discuss a plan to possibly bring a public rail system to Turner Field, talks tied to the 2016 expiration of the Braves Turner Field lease with Atlanta-Fulton County Recreation Authority.

- July. Cobb County officials and the Braves begin secret talks about a possible stadium deal that would move the Braves to a new stadium in Cobb.

- May 2012. The city of Atlanta enters talks with the Atlanta Braves about a broad redevelopment project around Turner Field that would improve fan amenities tied to the stadium

- Oct. 23, 1999 Turner Field hosts its first World Series game. The Braves lost to the New York Yankees, who would go on to sweep the series.

- Aug. 2, 1997 Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium is demolished to make way for a parking lot

- April 4, 1997 The $200 million Turner Field hosts its first game. The Braves defeat the Chicago Cubs 5-4.

- Sept. 1996-April 1997 Olympic stadium is retrofitted into a baseball-only, open-air, natural grass facility. Construction included the demolition of 35,000 seats. Turner Field seats 49,000 when it opens. The stadium is owned by Atlanta-Fulton County Recreation Authority and leased to the Braves.

- June 1996. At a cost of $207 million Olympic Stadium is built just south of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium and in time for the opening ceremony of the 1996 Summer Olympic games.

Kasim Reed never wanted to be the mayor who lost one pro sports team, let alone two. But as he heads into a second term, he now faces the world-class headache of grappling with the fallout of the Atlanta Braves’ declared move while figuring out what to do with a vacant Turner Field.

By all accounts, the mayor was among city officials and business leaders blindsided by the news that the beloved baseball squad wants to bold to the ‘burbs. Now he’s facing questions from others who want to know what went wrong and why.

“This is devastating, shocking news that they would even consider leaving,” said Atlanta City Councilman Michael Julian Bond, who was among the leaders who learned the news Monday. “I am equally appalled that negotiations were going on and (the City Council) didn’t know anything about it.”

Reed tried to put a good face on the move, wishing the team well and saying the city was “simply unwilling” to match Cobb County’s $450 million offer of public support to finance the construction. He later told Channel 2 Action News that he doesn’t consider the deal yet done.

“We have been working very hard with the Braves for a long time, and at the end of the day, there was simply no way the team was going to stay in downtown Atlanta without city taxpayers spending hundreds of millions of dollars to make that happen,” said Reed, who learned of the team’s decision on Thursday, just days after his re-election win.

Supporters said the mayor was unwilling to chip in public funds without a promise that the team would stay for decades, much like the concession City Hall extracted out of the Falcons to stay for 30 years.

“In no uncertain terms could Mayor Reed ask the city of Atlanta taxpayers to fund hundreds of millions of dollars with no dedicated revenue stream,” said Tharon Johnson, a Democratic strategist and a Reed confidante.

Hans Utz, deputy chief operating officer, said city officials have been in discussions with the Braves for 18 months over a broader plan that would extend the team’s lease on Turner Field, which will expire in 2016, upgrade the stadium and incite development in the downtrodden communities near the ballpark.

At times city officials and team clashed over those redevelopment plans and how large a role the Braves would have in defining the parameters and selecting the top bidder, a spot the Braves hoped they would earn.

Utz said city officials asked the Braves to submit a proposal outlining its requests, which the team did in September, asking for $100 million in city funds for infrastructural improvements and a continued revenue stream from development.

The city believed it had until this month to respond to the Braves’ last request and were stunned to learn the team was headed to Cobb, he said.

“No one blames the Braves for liking the Cobb County deal … but they surprised us by dropping it in our laps at this last second,” Utz said Monday. “I’m not sure what else we could have done.”

What happens to Turner Field now becomes a central piece of Reed’s second-term. Millions in public funds raised through tax allocation districts, aimed at spurring development, have yielded little more than a few ambitious plans.

Atlanta City Councilwoman Carla Smith, whose district includes The Ted, said the news came as a “punch in the chest.”

Now, she she’s worried about the nascent redevelopment plans for the area. Braves fan Richard Steventon, 36, who was eating lunch at a BBQ joint near the stadium, put it a different way.

“Take the stadium away from here and what do you really have?” he asked.

That question won’t be answered any time soon. Reed said the city has talked with several firms interested in redeveloping the Turner Field area, but that he expects any process that is “worthy of our city and strengthens our downtown” to take several years.

William Perry, the head of the Common Cause watchdog group, was among the critics who suggested that Reed had his eye on the wrong ball.

“It’s pretty hypocritical to let go of a team that plays 81 games a year in downtown,” he said, “while making the case that the city will crumble if it loses a team that plays there eight games a year.”

Utz takes umbrage with suggestions the city didn’t work hard enough to keep the team in town. He maintains city officials were operating in good faith to keep the Braves.

“We certainly can’t match a $450 million deal in 48 hours, which is approximately the amount of time we’ve had to react to it.”