Buford confronts change after racial turmoil

There are two powerful images for the city of Buford, the one most newcomers know and the one long-timers talk about.

The one more people are familiar with is of a cherished, proudly independent small town with dressed up sidewalks and schools, with loving, committed teachers that draw parents from elsewhere in the suburbs of Gwinnett, Hall and south Forsyth counties.

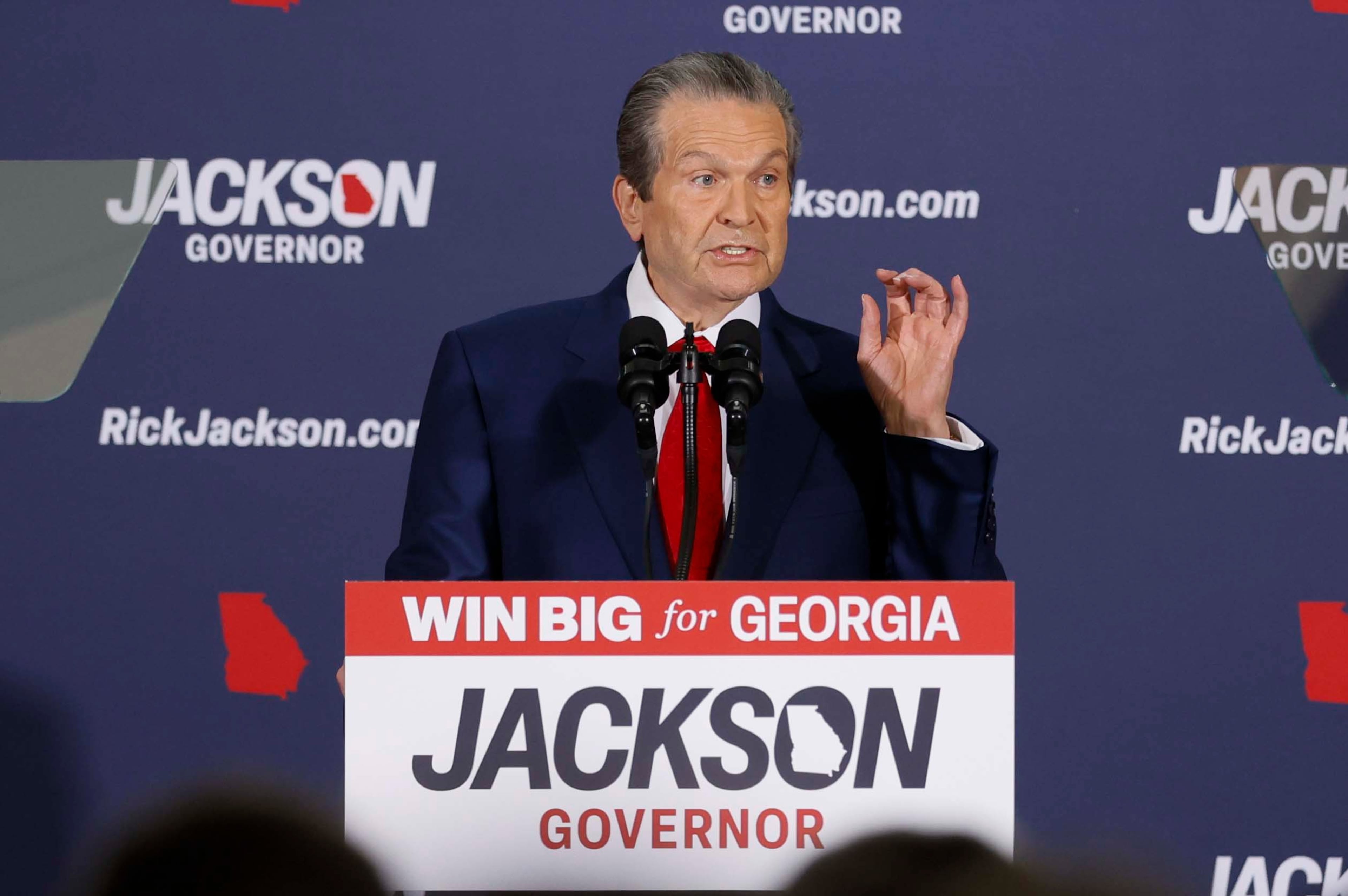

“We’re an island in over a million people,” said Phillip Beard, long the most powerful man in town.

Then there’s the lesser-known image of Buford. Where some long-time residents see Beard and a small group of families with power to run things as they wish and where contentions of nepotism, a lack of transparency and hardball governing tactics are undercurrents.

The collision of those two images poured out in a most public way over the last two weeks.

Buford School Superintendent Geye Hamby resigned days after The Atlanta Journal-Constitution wrote about audio recordings of someone, purportedly of Hamby, unleashing racial slurs and threats of violence in a tirade apparently aimed at African-American temp workers.

On Friday, Beard, the chairman of both the City Commission and the Buford school board, confirmed to the AJC that he was the second person heard talking in the recording but he suggested the audio may have been spliced together from different conversations. And he said if he had heard racial slurs "you would have heard Phil Beard getting after him about it." Beard doesn't use racial slurs in the audio but doesn't object to them either.

The new revelation hits an already reeling city.

Questions from residents are piling up, including some raised when hundreds of people packed a recent school board meeting.

Did Beard and other public officials know they had entrusted a possible racist to run the school system? Is it time to elect new leaders, ones not connected by blood, marriage or paychecks to the families now running the city?

“Vote, guys,” Patrick Gantt implored other residents at the meeting. “We have to make a difference.”

‘Nepotism is everywhere’

There’s a flip side that Beard latches onto: changing leaders could derail Buford’s successful drive to rebuild the community into a prettier place.

“We don’t need outsiders coming in and tearing it all down,” said Beard, the architect of much of the city’s transformation.

He’s had lots of time to make changes. At 78, he’s been in elected office for Buford for more than 40 years. That makes him one of Georgia’s longest serving elected municipal executives.

Often, no one runs against Beard for the unpaid leadership positions.

“You’d think after awhile people would get tired of me and put me out of the job,” he said.

He also said later, “If it’s all this abuse and non-concern up there, it would show up at the polls.”

(He is elected as chairman of the city commission, which automatically gives him an un-elected position leading the school board.)

Beard’s next generation is already taking its place in line. His nephew, Brad Weeks, ran unopposed for one of the other seats on the three-member City Commission. The uncle said he urged his nephew not to run, specifically because he didn’t want to face questions about the family’s expanding influence.

Branches of family trees weave through Buford’s government, elected offices and schools. One of City Commissioner Chris Burge’s brothers heads up the city recreation department and has been with the government for many years. A son is over the water department, which Beard said the father played no role in. The gas system superintendent sits on the city’s school board.

Some residents complain that some of the city’s choice jobs go to the most powerful families and the connections are passed down to new generations.

“Nepotism is everywhere,” said Kyah Slaton-O’Connell, a 26-year-old Buford native.

There are new buildings in the city: a high school is under construction. But in terms of the way things are run, how much has Buford changed in 26 years? Slaton-O’Connell asked during a school board meeting.

“None,” came a reply from the audience.

LAWSUIT: Buford schools chief recorded in racist rant

MORE: Gwinnett NAACP seeks probe of Buford schools

Later in the week, a man who has lived in Buford since childhood described what he called the double-edged sword for Buford. Keeping some of the same people in place might create some continuity for the city. On the other hand, he said, it might lead to abuse or limit the city’s options.

“You’ve got to wonder,” he said, “is one family’s set of values the embodiment of what the entire city wants?”

Scott Snedecor, who owns the local S&S Ace Hardware, has his own thoughts. He said Buford officials are smart about how they spend money, such as fixing equipment if they can rather than automatically running out to buy new. And when they build facilities, they look to do it in a way that will last into new generations.

‘It was extremely painful’

“My city,” said Beard, “is an open door to everybody.”

Dealing with Buford’s government, though, isn’t for wimps. And some worry that even relatively minor dissent comes with a potential cost.

Mary Ingram, a former Buford paraprofessional who filed a federal discrimination case that exposed the now-infamous audio recordings, contended things went south for her when she pushed to incorporate the color gold — representing the city’s pre-integration black school district — in a new facility. A school system attorney said she was fired for cause and neglect of her duties.

Then there was a Buford school bus driver who claimed in a 2010 lawsuit that Buford's now-ex superintendent targeted her for firing after she posted a link on Facebook to a news story about city plans to spend more than $600,000 for artificial turf on sports and band practice fields. She described the post as "today's humor," according to the lawsuit. The city disputed her description of events.

And there was the case of Buford officials repeatedly refusing to permit opening of an entrepreneur’s new garden center, at one point determining that his building was three inches too close to a property line. A jury ordered the city and two of its managers to pay $291,000 for ultimately killing the man’s business. The city appealed and eventually the size of the award was dramatically reduced.

Just trying to get basic information from the city government can take extra work.

Emails for most school board members and city commissioners hadn’t been posted online on main city pages. Agendas can be difficult to get in advance of city meetings. And the first broad email the school system sent to parents about the superintendent turmoil and changes was Wednesday evening, five days after the superintendent resigned.

Earlier in the week, a resident had urged school officials to change their ways.

“Be transparent so we don’t feel there’s any more cloak and dagger behind your back,” she said. (In the wake of complaints, the school system recently publicized an email to help parents share with board members.)

But on a recent visit to Buford’s imposing city hall, an AJC reporter spotted a stack of agendas remaining from a City Commission meeting weeks earlier. A city worker said she had to contact higher ups to see if it was OK for the reporter to take one. The message relayed back from City Clerk/Planning Director Kim Wolfe: fill out a request under Georgia’s Open Records Act; the city has three days to respond to your request.

Jeremy Kennedy became so frustrated by his interactions with the city that he detailed the experience online in a report he titled “The Bullies, The Bigotry, And The Bias.”

“Trying to go through the application process one time was enough for me,” said Kennedy, a tech project management contractor who hoped to open a small miniature golf business on a former gas station property downtown. “It was extremely painful.”

One frustration: rules and dictates that seemed to pop up out of thin air, he said.

Tentacles spread across five counties

Buford has remained remarkably self-contained, for a community of 15,000 people surrounded by suburbs.

Despite its size, the city operates its own public school system (four schools in all), garbage pickups, water and sewer service, electric utility and a natural gas system, a money-maker that spreads far beyond the city’s borders and into five counties. There’s also the commanding Buford Community Center along Buford Highway, including the Phillip Beard Ballroom. (Beard said he opposed the naming.)

Rates for water, sewer and residential collection are essentially the same as they were in 1973, Beard said. And property taxes for schools are lower than they are for Gwinnett schools. Now, the parents of more than 1,000 children from outside Buford pay $2,000 a year tuition for highly-rated Buford schools.

Beard found other ways to boost the city. He became an early local proponent of installing landscaping, sidewalks, metal benches and an extra heavy slathering of metal posts for street lights. Some of the city’s old streets are still lined by ditches that overflow when it when it rains, but residents have noticed improvements.

“Look at my city,” Beard said. “Go anywhere. Look how clean our town is, how manicured it is.”

For years, though, Beard and other commissioners resisted much of the residential growth that flooded the rest of Gwinnett, diluted the control of long-time residents, strained budgets and made the county one of the nation's fastest growing and eventually most diverse in the state. Between 1990 and 2010, Gwinnett's population increased by 128 percent. Buford's grew only 39 percent, slower than Georgia overall.

Beard argued that new businesses that paid taxes but consumed relatively little in public services would be better for the city. Beard has been a real estate investor for much of his life and that, too, has sparked skepticism from some residents who question whether there’s ever a collision of his city and personal financial interests.

“I’ve stayed totally out of any conflicts with my city,” Beard said.

In the 1980s, Beard and Buford’s then-city attorney sold land to a partner, who quickly sold as well, according to an AJC story from that era. The city commission rezoned a few months later to allow a large private landfill, according to the report. Beard abstained from the commission’s vote, according to the article.

Even today, Beard bristles at the subject, saying there was never an issue and that the landfill pays the city more than $1 million a year.

‘A Defining Moment’

As Buford has grown, the proportion of African Americans has declined. Decades ago, Beard said, African American residents made up a third of the city’s population, which included neighbors he hung out with as a child. The most recently available Census numbers place the black population at 10.5 percent. That’s a drop from 13.4 percent in 2010. Buford remains predominantly white.

Residents point out that there currently are no minorities on the city commission or school board. And there has been little official enthusiasm in the past to adopt voting by district, which could increase the chances of minorities being elected.

Still, the city now tarnished with the image of racial slurs also had the first Georgia school system to be led by an African-American woman. Beauty Baldwin, the daughter of a sharecropper, got the job in 1984. And one of the main roads into Buford’s education complex is named after another African American who served on the city’s school board.

Maybe more change is coming in the wake of the audio recordings of racial slurs, said Avery Headd, the pastor at Poplar Hill Baptist Church in Buford.

“We have to view this day, this time as a defining moment in the city of Buford,” Headd said at the recent school board meeting. “This is a defining moment for us.”

Other shifts for Buford are already underway. More than 1,000 lots in the city are slated for new homes, many with lofty prices, according to Beard.

He’s considered the ramifications.

“These are going to be people that are harder to deal with,” he said.

They might even think they are smarter than him, he said. But it doesn’t sound like the most powerful man in Buford is ready to give in, as long as his health holds up and the controversy over racial slurs doesn’t get in the way.

Said Beard, “We have got a lot of good left in us that we can do.”

THE STORY SO FAR:

Aug. 21: After The Atlanta Journal-Constitution publishes details of a race discrimination lawsuit, which alleges Buford schools superintendent Geye Hamby was recorded saying racially offensive slurs, Hamby is put on leave by the school board.

Aug. 23: A court filing alleges that Phillip Beard, longtime chair of Buford's city commission and school board, was with Hamby when he made the racist rant but did not object to it.

Aug. 24: Hamby resigns his post as superintendent, apologizing for "any actions that may have created adversity for this community and the Buford School District."

Aug. 27: Joy Davis came out of retirement to become the new interim school superintendent for Buford City Schools.

Aug. 31: Beard confirms his is the second voice on the recording, which he had heard rumor of last year, but says he hadn't heard the racial tirade or allegations of it until recently.