HOW WE GOT THIS STORY

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has been on top of the Braves stadium story from the very beginning. On Thursday, the city of Atlanta released more than 600 emails between the city and the Braves in response to Georgia Open Records Act requests made by the AJC and other media. AJC reporters pored through the emails and attachments, which detailed the private discussions between the city and team officials. The AJC also interviewed key city and Braves officials to provide the fullest view yet of negotiations that ultimately broke down and led to the Braves’ decision to move to Cobb County.

What the Braves wanted: In short, the team sought control over redevelopment efforts at Turner Field and ways to increase revenue streams for future renovations. But the team and city couldn't reach an agreement over how to accomplish that. Documents released by the city show the Braves asked Atlanta in April to give them ownership of the nearly 60 acres surrounding Turner Field. When told that would require an open bidding process, the Braves decided against that option. Atlanta and Braves leaders then began discussing a redevelopment effort. The Braves wanted to define the parameters of the bidding process but also apply for the bid and select the winner.

TIMELINE

Fall 2011: The Atlanta Braves hold preliminary discussions with then-Atlanta COO Peter Aman over renewing its lease for Turner Field, future development and funding concerns.

June 2012: Atlanta begins formal negotiations with the team over lease renewal and future development efforts.

January: The Braves inform the city of their desire for the city to assume control of Turner Field, instead of the Atlanta-Fulton County Recreation Authority.

March 20: Braves executive vice president Mike Plant sends note to Deputy COO Hans Utz expressing that the team is “not feeling real good about how we are being passed around.” Utz composes a memo to city leaders about the team’s need for more attention.

April 17: Mayor Kasim Reed meets with Plant and Braves CEO Terry McGuirk to discuss the Turner Field project and ask for the land around the stadium. City officials respond the land must be sold through a competitive bidding process. The Braves decline that option. Parties turn their sights toward crafting a request for proposal for redevelopment.

May: Utz provides a counteroffer to the Braves for how to pursue redevelopment efforts and gives the team three paths for moving forward.

July: Utz and COO Duriya Farooqui meet with Plant to discuss the project, expecting the Braves to have selected a path in pursuing redevelopment efforts. They clash again over the Braves’ desire to control the redevelopment bidding process. This same month, Braves officials hold their first discussions with Cobb officials.

August through October: City officials, the AFCRA and the Braves negotiate improvements to sewer drainage problems at Turner Field.

September: The Braves give the city a 16-point proposal outlining desires for lease renewals and redevelopment. By now, the team has indicated its desire to help craft the request for proposal and select a winner for the bid.

Nov. 5: Reed is re-elected to a second term as mayor.

Nov. 6: Plant sends Reed a text message asking for a meeting.

Nov. 7: Braves leaders inform Reed of plans to relocate the team to Cobb County in 2017.

Nov. 11: The Braves break the news to a small group of reporters in a surprise announcement.

Nov. 27: The Cobb County Commission approves by a 4-1 vote the use of $300 million in funding for a new Braves stadium project.

SOURCES: Documents released by Mayor Kasim Reed's administration, emails obtained through an open records request and AJC reporting

The Atlanta Braves prodded Mayor Kasim Reed’s administration for more attention on Turner Field, but what the team really wanted was something city officials said they couldn’t give: total control.

Hundreds of emails released last week by the city show the Braves’ dismay at the slow pace of negotiations about a new lease. A senior executive complained in March about the team “being passed around” while the city approved a $1.2 billion stadium deal with the Falcons. The Braves saw the Falcons deal as fast-tracked while they had little to show after two years of talks with Reed’s administration.

But despite the team’s dissatisfaction with the city’s responsiveness, the Braves’ move to Cobb County ultimately boils down to this: The city couldn’t give the Braves what they wanted — total control from concept to redevelopment of 55 acres the city and Fulton County own around Turner Field — because of conflict-of-interest laws.

The Braves at one point wanted to be given all the land around the downtown stadium. When told that ownership of the land could only be transferred through an open bidding process, the Braves didn’t want to risk losing the property to another bidder, city officials said.

The team later wanted to craft the bid process for the stadium-area redevelopment, apply for the work and select the winner — something city officials said was illegal. Under those conditions, they explained, the Braves would have so great an advantage in winning the bid that the project could not have avoided a court challenge.

“I’m not the expert on state law,” Braves executive vice president Mike Plant told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution last week. “The city said those were the laws they were bound by, and unfortunately those were not going to work for us.”

Those legal hurdles plagued the talks that began in late 2011 and broke down two years later. Reed’s administration was still considering a 16-point development proposal the Braves submitted in September when the team abruptly informed Reed on Nov. 7 that it was moving to Cobb.

There, the team plans to start anew with a $672 million stadium near Cumberland Mall flanked by an adjacent $400 million mixed-use campus to be developed by the team on property it will own.

That was an offer Reed has said Atlanta couldn’t match. Nor did city officials feel they had an opportunity to counter. By the time the Braves told city officials of their deal with Cobb, a proposal funded by $300 million in taxpayer dollars, they weren’t looking back.

“We never knew they had a deal on the table we could’ve responded to (before Nov. 7),” said Deputy COO Hans Utz, who led talks with the Braves on behalf of the city.

Just four days after Plant informed the mayor of the team’s plans, the Braves announced the stunning news.

Atlanta officials have said they weren’t willing to tap into the city’s general fund for a Braves deal in light of the city’s nearly $1 billion backlog in infrastructure needs.

With that in mind, Reed said the public wouldn’t support two pricey stadium deals in a single year.

“We believe the public’s appetite for two taxpayer-financed sports stadiums at once (is) not there,” Reed spokesman Carlos Campos said Thursday.

On Thursday, the city released more than 600 emails spanning two years of negotiations. The messages, however, do not include privileged communications between lawyers and clients.

The letters and interviews with Braves and city officials last week offer the fullest view yet of the private wrangling that unwound in November.

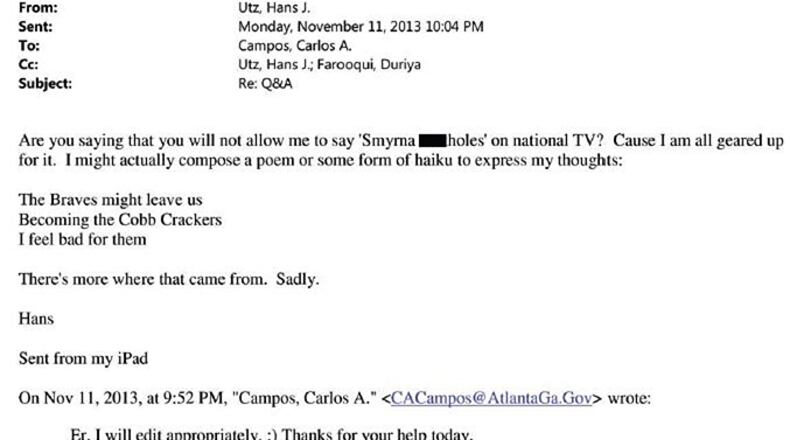

They’ve also resulted in Utz’s suspension without pay after emails sent the night of the Braves’ bombshell news show the official using racially insensitive and profane language related to Cobb.

Utz apologized Thursday, and both he and Plant said the disparaging comments did not reflect the tenor of their relationship or the negotiations. Several Cobb leaders and prominent officials have criticized the remarks, with one calling for Utz’s firing.

‘You need to light a fire’

In October 2011, Plant said the Braves and the city agreed to try to resolve three key issues: the financial and operational aspects of future mixed-use development around Turner Field, how to fund extensive infrastructure improvements and other renovations around and inside the stadium, and changing the team’s operating relationship with the Atlanta-Fulton County Recreation Authority.

“Those three tenets … had to be resolved,” Plant said last week.

In early 2011, Falcons stadium negotiations began between the football team and the state. The talks fell apart early this year when state lawmakers balked at increasing the debt limit of the Georgia World Congress Center to issue bonds for the new dome.

That’s when Reed and the city stepped in and held rapid negotiations to salvage a deal to keep the Falcons downtown.

And that’s when talks with the Braves slowed and the team’s relationship with the city showed the first signs of fraying, emails show. Atlanta passed the Falcons stadium deal after roughly two months of discussions at the city level. Plant wanted similar speed.

“(If) you look at it from our perspective, we met with the mayor and (then-city COO Peter Aman) in October of 2011,” Plant wrote in a March 20 email to Utz. “(Eighteen) months later we are no further along in resolving any of the 3 major components of our discussion presented at that time. on the other hand, we have watched the state pass a major funding initiative for a new falcons stadium and that has now gone thru all the proper channels including approval by the city council in 7 short weeks. Not feeling real good about how we are being passed around.”

Utz then alerted current city COO Duriya Farooqui that the Braves needed “some love,” emails show, and he arranged a meeting with Reed.

Braves CEO Terry McGuirk and Plant met with the mayor in April, when Reed assured the team that it would receive his full attention, Campos said.

In April, Utz and Brian McGowan, the head of the city’s economic development arm, toured the Colorado Rockies’ stadium in Denver with Braves officials.

But in May, the city’s responsiveness to a meeting request again ruffled Plant, who wrote that “9 weeks start to finish on the other guys (the Falcons). we are going to fall behind. You need to light a fire over there.”

Utz, however, responded: “9 weeks start to finish after 20 months of negotiations that had hammered out the basic outline of a deal. … We are not starting at the same point and you know it. Your point is still well taken, and we are pushing forward.”

Cobb enters picture

Though the Braves complained the Falcons stadium deal slowed the pace of the negotiations, the deal ultimately fell apart over legal hurdles involving control of any redevelopment.

In May, Utz provided three paths the team could take in redevelopment efforts, including one in which the Braves would help craft a request for proposal and then choose the winner. City leaders then met with Plant in July, expecting the Braves to have made a decision on a path forward. But they hadn’t.

Atlanta officials didn’t know that around the same time, Plant held his first meeting with Cobb Commission Chairman Tim Lee to discuss moving the team to the suburbs.

Still, the Braves ultimately issued a proposal in September outlining their wish list for Turner Field, with the understanding they would not apply for the contract, but help choose the winning bid. That’s what the city was vetting when the Braves announced their deal with Cobb officials.

Plant has acknowledged that while the Braves began negotiations in 2011 by stating they might relocate, the possibility of moving wasn’t a continued threat. Plant didn’t inform the city he was talking to Cobb until four days before the Braves announced their deal.

“If (team president) John Schuerholz and I had said, ‘Oh, by the way, we’re starting to have discussions with someone else,’ it’s not realistic to think that would have worked out in the best interests of our organization and our fans long-term,” Plant said last week. “It’s not realistic to think that could have been a positive working relationship for either side.”

More importantly, Plant had already assured his Cobb partners that they wouldn’t be used for leverage.

“Tim Lee and I looked each other in the eye,” he said, “and I made a commitment to him that we are not using you as a stalking horse.”

Move didn’t seem possible

City officials have noted a few key differences in what the Braves wanted and what the Falcons received.

Atlanta is committing $200 million in bonds backed by hotel-motel taxes for a $1.2 billion stadium, with Falcons owner Arthur Blank agreeing to pay up to $70 million in infrastructure improvements and $15 million to impacted communities.

Atlanta’s hotel-motel taxes can only be used toward the Falcons stadium, and thus directing those dollars to other projects would have to be decided by the Legislature, which did not increase the Georgia World Congress Center’s debt limit over potential political backlash.

Reed has maintained it didn’t make sense to spend hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars on a team that would remain in the region, but he noted that he would have if the Braves were leaving metro Atlanta.

But if you ask Plant, the thought of the Braves leaving at all didn’t seem to cross the city’s mind.

“I will say, in looking back on this, (the city) probably didn’t think there were any other options in the metro area of Atlanta that we could explore,” Plant said.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured