Congressional candidate Deborah Honeycutt paid her husband and a company connected to her family about $62,000 combined from her campaign account for consulting, financial advice and other expenses between 2007 and last year, public records show.

Under federal rules that allow candidates to police themselves, that’s all fine. In fact, watchdog groups say many candidates have resorted to the practice, including Honeycutt’s potential opponent, U.S. Rep. David A. Scott (D-Ga.), who paid more than a half-million dollars in campaign funds to relatives and the family business between 2002 and 2007.

Of the $62,000 Honeycutt spent, $44,500 went to her husband, Andrew, for campaign management, strategy and payroll costs.

Her campaign finance reports also show a $17,500 payment went to Travis Cheney Corp. State corporation records show the mailing address for the business is the couple’s home in Fayetteville and that Andrew Honeycutt is the company’s registered agent. Those records also show the company was created less than a month before it received the campaign payment.

Federal rules say candidates may pay their relatives and family businesses from campaign funds so long as those payments are for bona fide campaign expenses at fair market rates.

The rules leave it up to the candidate to determine what are bona fide expenses, said Meredith McGehee, policy director of the Campaign Legal Center, a Washington-based watchdog group.

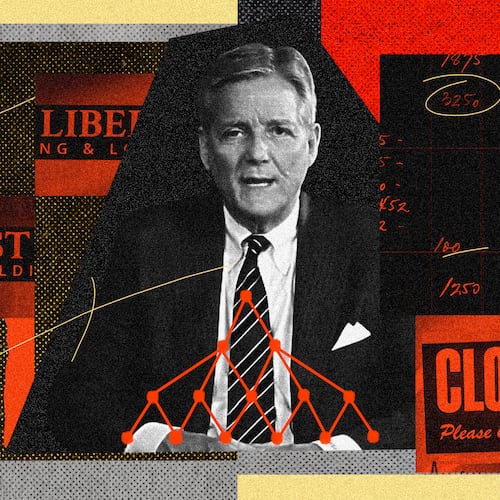

Campaign finance watchdogs say candidates' payments to relatives raise concerns about nepotism. Attempts to ban the practice have failed in Congress, according to McGehee's group, which is led by former Federal Election Commission Chairman Trevor Potter..

“In essence, it is a self-dealing transaction,” McGehee said. “It raises the appearance to the public that you might just be out there using other people’s money to enrich your family or yourself.”

Deborah Honeycutt, who is locked in a GOP primary runoff with Mike Crane for the Atlanta area’s 13th District, referred questions about her campaign expenditures to her husband and her campaign staff.

“I don’t go down line by line over that stuff,” said Honeycutt, a family doctor. “The stuff is done by them and the treasurer.”

Her husband, the dean of an online business school, said he previously served as his wife’s campaign executive. Federal records show the last payment he received from the campaign was made in March of last year for $3,500. He said that paid for his help with marketing and strategy for her unsuccessful 2008 campaign against Scott.

“I have a doctoral degree in marketing from Harvard. And that is cheap for what I generally get,” he said. “I’m not making any money off the campaign.”

Regarding the payment to Travis Cheney Corp., he said the campaign paid the company for a report showing why his wife should no longer work with a Washington direct-mail firm previously called BMW Direct. Now called Base Connect, the company says it raised $5.1 million for her 2008 campaign.

Andrew Honeycutt declined to make Travis Cheney’s report about that company’s work available to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. He also declined to identify who owns Travis Cheney and explain why his wife’s campaign finance report gives an Owensboro, Ky., address for the business instead of his residence. Georgia corporation records show the company is delinquent in paying this year’s annual registration fee, which was due April 1.

Meanwhile, Base Connect says on its Web site that of the $5.1 million it raised for Honeycutt’s campaign in 2008, $1.3 million went directly to her campaign while the rest covered postal expenses, Base Connect’s fees, bills from contractors and other expenses.

Andrew Honeycutt said Travis Cheney’s analysis looked at financial reports and multiple companies connected to Base Connect.

“The payment was to do an analysis of BMW because they raised a lot of money,” he said. “We just wanted to see if it could be done better.”

Michael Centanni, Base Connect’s chief operating officer, spoke positively about his company’s work for Honeycutt in 2008.

“In terms of how everything worked, it was textbook,” he said.

In contrast to the 2008 campaign, Honeycutt has raised just $183,033 for this year’s election, federal records show.

Scott spokesman Michael Andel said Scott is not paying relatives with campaign money to work on his current re-election bid, and past payments to family members were for reimbursable expenses.

In 2007, the AJC reported that since first running for Congress in 2002 Scott had paid more than $500,000 from his campaign account to four family members and his family's advertising business. The Scotts said they decided to staff the campaign themselves after spending huge amounts of money on consultants in his first campaign.

Andel said this week that the congressman also chose to work with his family business because it was more efficient to do so and that the payments to that company covered its costs. There was no evidence the Scotts broke any campaign laws.

“The campaign in the past had reimbursed the advertising company for media purchases,” Andel said. “This was stopped in an effort to eliminate any questions about campaign expenditures.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured