Atlanta water outage linked to systemwide leaks

A water outage earlier this month that disrupted Atlanta’s water system for more than a day has roots in a problem that has long bedeviled the city: How to stop water from leaking out of a decayed system?

A 2017 city audit partly attributes the high water loss in the city to an agreement with the federal government that directed nearly $2 billion in repairs to the city’s dysfunctional sewer system.

The agreement, called a consent decree, forced the city’s Watershed Management Department for the better part of two decades to heavily invest in upgrading the city sewers, possibly at the expense of maintaining the water supply system, the audit found.

VIDEO: Previous coverage of this issue

Today, the 2,600 miles of pipes that deliver drinking water to roughly 1.2 million people each day are riddled with leaks.

“Focus on consent decree projects may have resulted in under-investment in drinking water infrastructure,” the city’s audit found.

As city officials last week discussed what went wrong in the Dec. 3 outage that led to a day-long boil advisory, questions also surfaced about a toxic relationship between between managers and rank-and-file employees overseeing the fragile water system.

The 2017 audit found that the city loses as much as 30 percent of the water produced, placing additional stress on an already taxed system and driving up customers' rates.

The City Auditor’s Office report also found that city residents paid the second highest rates of the 30 largest cities in the country during 2015. Only Seattle was higher.

“Excessive water loss increases water rates by inflating production costs and by adjusting the amount of water billed to customers,” the audit said.

Infrastructure needs

At a Atlanta City Council utilities committee meeting last week, the city’s watershed commissioner, Kishia Powell, described the struggles her agency has had trying to get a handle on the water loss problem.

In fact, it was preparation for an upcoming audit that sent maintenance crews to the Hemphill Water Station west of Midtown to work on two meters that measure water loss, when one of the pumps shut off. Workers had failed to set the meter in maintenance mode, which triggered a false alarm that shut down two high service pumps.

“We have been trying to improve our accounting for water loss,” Powell said. “In order to do that, we have make sure that our metering infrastructure is always properly calibrated.”

The system’s pressure dropped, causing faucets in downtown dry up. While agency restored pressure in about an hour, the disruption raised concerns about potential contamination. So customers were under a boil order for 26 hours until tests confirmed that the water was safe to drink.

City Council President Felicia Moore said the episode should serve as a wake up call about the condition of the water system.

“We have an infrastructure and it has needs,” Moore said in an interview. “If you don’t tend to those needs, these things can happen.”

The 2017 audit said that some water loss could be attributed to accounting errors, but most occurred because of leaks in aging distribution system serviced by ancient pipes.

“One of main transmission lines serving the city was installed in the 1890s,” the audit said.

An under-investment

Today, the Watershed Management Department is in charge of both the city’s sewer system and the drinking water system.

In the 1990s, the city faced a sewage crisis. Heavy storms sometimes washed raw sewage into parks and streams. The spills were blamed for killing off wildlife in waterways, introducing harmful pollutants and impairing water quality.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency sued the city in 1998, leading to a consent decree agreement that levied $2.5 million in fines against the city and initiated a massive construction plan now projected to last until 2027, according a recent U.S. Environmental Protection Agency report.

The report concluded that the city is largely compliant with the decree.

However, the sewer improvements may have had an negative effect on the water supply system.

Since 2003, the city has spent nearly $ 2 billion to comply with terms of a consent decree which required repair to its sewer system and that may have have led to neglect of the drinking water system, the city audit last found. During the same period it spent billions to fix the sewers, the city spent about $350 million on the drinking water infrastructure, the audit found.

“Focus on consent decree projects may have resulted in under-investment in drinking water infrastructure,” the city’s audit found.

‘Salaries a bit all over the place’

At the council committee meeting last week, Powell not only faced questions about the outage from elected leaders who oversee her department, but also criticism from current and former city employees.

The employees expressed anger over low morale, poor working conditions and a patronage system that rewards unqualified candidates with jobs because their political connections. They said these problems were threatening the agency’s ability to carry out its mission.

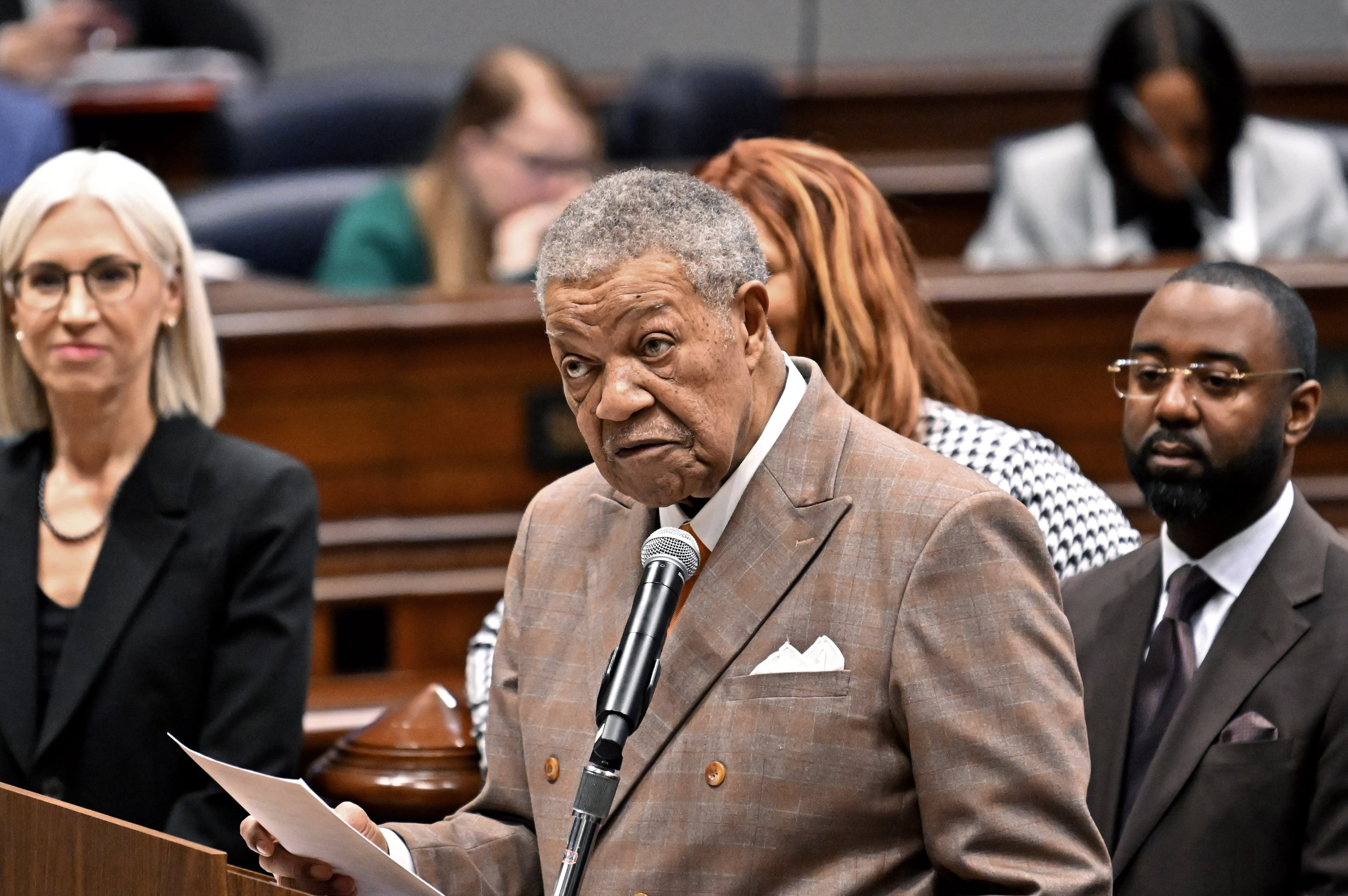

Charles Robinson, a former city employee, told the council that some managers in the watershed department escape accountability and there’s nothing employees can do when their actions harm the public. He said nepotism runs thick in the department.

“This is why the city is ran inefficient, top to bottom,” said Robinson, who spoke on behalf several employees at the meeting.

Powell, who took over the department in 2016, acknowledged the uneven pay.

“Salaries have been a bit all over the place and not necessarily tied to years of experience,” Powell said. She added that the Department of Human Resources is missing years of experience data for some employees.

Powell declined to address allegations of patronage within her department, but she said she was meeting with employees to hear them out, including some of the employees at committee.

Not all the employees seemed to agree with their boss.

One told the committee when employees ask to meet with managers, the meeting won’t happen for months, and the manager arrives with a prepared script.

“When the questions start to get hard and the lies can’t keep up, they got to go,” the employee said. ‘They have to take a phone call.”

Powell said she recognizes the agency has problems and she’s committed to fixing them.

“I understand there is a history of concerns here,” she said. “We are trying to work through them to get to a better place. But we are not there yet.”