After previous interventions failed to show results, Atlanta Public Schools turned to a drastic tactic to try to improve one of its worst-performing schools.

The district replaced two thirds of Perkerson Elementary's teachers after the school board unanimously agreed in March to require everyone to reapply for their jobs and to let the principal hire a different staff.

The decision — which officials described as "tough" and "next level" — illustrates how far APS will go to implement its turnaround plan for bottom-rung schools, now in the third year. It includes hiring charter groups to run some, merging and shutting others, and paying for academic help and social services.

VIDEO: More on APS

In recent years, the district made all employees in a school reapply for jobs in about a dozen instances. But before Perkerson such staff overhauls had been used only when schools merged, closed and the students were sent to other schools, or were handed over to outsiders to run. A spokesman said the district isn’t considering similar actions at additional schools “at this time.”

APS officials said the Perkerson shakeup was necessary because it fell further behind despite receiving extra money and attention.

“We really needed to bring in a new mindset,” said Principal Tony Ford. “I think that we had some really hard-working professionals in the building, but we did really need to start thinking about a new approach and how to help our students to be more successful.”

Experts caution that widespread teacher changes — known as “reconstitution” — come with mixed results, including possible short-term gains but higher turnover.

“The upshot is that this is a pretty risky strategy and that a lot of the studies show unintended negative consequences,” said Jennifer King Rice, dean of the University of Maryland College of Education.

Educators and politicians have focused on improving troubled schools in an era of increased accountability, which took off with the No Child Left Behind Act signed in 2002. In 2016, Gov. Nathan Deal pushed a constitutional amendment to empower the state to take over failing schools. Voters rejected the proposal, but as APS launched its turnaround plan it was in danger of losing control of Perkerson and other schools.

Since then, a new state law created a chief turnaround officer, and the state can use the threat of financial pressure to get districts to accept interventions.

APS plans to spend more than $45 million this year on turnaround efforts.

It’s easy to see how Perkerson became a target.

A state report card gave it an F-grade every year from 2013 to 2017. Only 10 percent of its third-graders tested at "proficient" or higher last year in English language arts, a critical marker of reading skills. About half of the students have been absent six or more days in recent years.

APS has given Perkerson reading and math specialists, provided support to students outside of class and amped up staff training.

Perkerson still faltered.

Of the 17 Atlanta schools receiving the most intensive turnaround support, only two saw their state rating slip from 2016 to 2017. One — Price Middle School — has been run by a nonprofit operator since last year. The other was Perkerson, though its latest score beats a handful of Atlanta schools.

The school's state report card score — based largely on test results — is below both the APS elementary average in the high 60s and the Georgia average of 72.9. Perkerson's score fell by nearly 1 point to 56.9 in 2017.

“This is the one that made no movement, and it was in part a bit of a staffing issue,” Superintendent Meria Carstarphen told board members in March.

Credit: Jenna Eason

Credit: Jenna Eason

Ford, hired as principal last year, pointed to leadership changes as a possible reason the school has struggled. He’s the third principal in almost as many years. “In any organization when the leadership is inconsistent your staff is trying to regain their footing around what those expectations are,” he said.

The district’s answer? More change.

Ford kept 13 of the 39 teachers from last year. Out of a staff of 71, 20 former Perkerson employees no longer work for APS and seven work elsewhere in the district.

The school hired a mix of veterans, “hungry newbies” and teachers with mid-level experience, Ford said. He looked for teachers with an understanding of pedagogy, classroom management skills and “heart for the work,” he said.

That’s crucial in a school where many students live in poverty and teachers can become fatigued because they serve as caregivers as well as educators, he said.

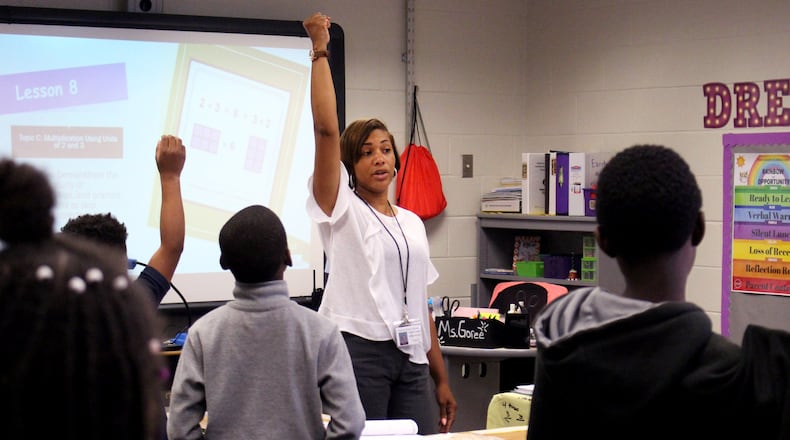

Sandrea Goree, a third-grade teacher hired back for her sixth year, said learning she wouldn’t be guaranteed a job was “a little nerve-wracking.”

“At first you’re kind of in limbo,” she said. “But once we got through the process, I knew … it was going to be for the best.”

The staff has a shared vision, and “the school feels amazing,” Goree said.

Credit: Jenna Eason

Credit: Jenna Eason

Skeptics wonder how children benefit from having new teachers replace familiar faces. “They aren’t vested into the community and into the district,” said Verdaillia Turner, president of the Atlanta Federation of Teachers.

Richard Ingersoll, an education and sociology professor at the University of Pennsylvania, said sweeping staff changes are a “last resort” that can be demoralizing to teachers who are “blamed for things over which they have no control.”

“I get why it’s done. You have these chronically low-performing schools, but the problem is that it’s an untested assumption. The assumption is that the teachers are the problem,” he said. “It’s difficult because teachers should be held accountable in some sense, but on the other hand how far do we go?”

He said changing the staff can trigger more teacher turnover, which Rice observed when she studied reconstitution in Maryland.

“The teachers came in, they tried to make a go of it, but it was so chaotic. The word we often use is ‘frenetic.’ The resources were dumped into the school but they weren’t the resources that they needed,” Rice said.

District officials agree that new teachers alone won’t save a school.

Ford said he doesn’t have any new full-time positions this year, but he has flexibility on using the $562,468 budgeted for Perkerson’s turnaround efforts.

He created the role of a parent liaison. Perkerson will continue to offer “wraparound” support to make sure students have food, uniforms, counseling and social work services. He revamped the dual-language immersion program. Starting with this kindergarten class, students will receive most math and science instruction in Spanish and most language arts lessons in English.

School goals include reducing behavior infractions and hiking English and math test scores by 5 percent.

Perkerson’s new teachers have embraced the challenge. Christin Dickens, who is starting her 12th year as a teacher but is new to APS, said she looked during her job search “for where the struggle was.” Instead of scaring her off, the decision to restaff the school “was exciting to me.”

“I saw … that may not be the prettiest thing to look at, but this is the potential to shine bright like a diamond,” Dickens said. “What is important is the main ingredient — the want to. That’s what we need.”

The story so far:

In 2016, Atlanta Public Schools adopted a plan to improve low-performing schools. It merged and closed some, hired charter groups to run others and invested millions in academic and other student support and teacher training. Perkerson Elementary School received extra help but still failed to make academic gains. In March, the school board agreed to “reconstitution,” meaning staff would not be guaranteed their jobs. When school started this year, two thirds of the teachers were new to Perkerson.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured