Some metro Atlanta students locked out of virtual classrooms

On any given day, more than 100,000 of metro Atlanta’s K-12 students are not logging into distance learning programs, the primary method of instruction since school districts shuttered brick-and-mortar buildings to help curb the coronavirus’ spread, according to an analysis of data collected from several districts.

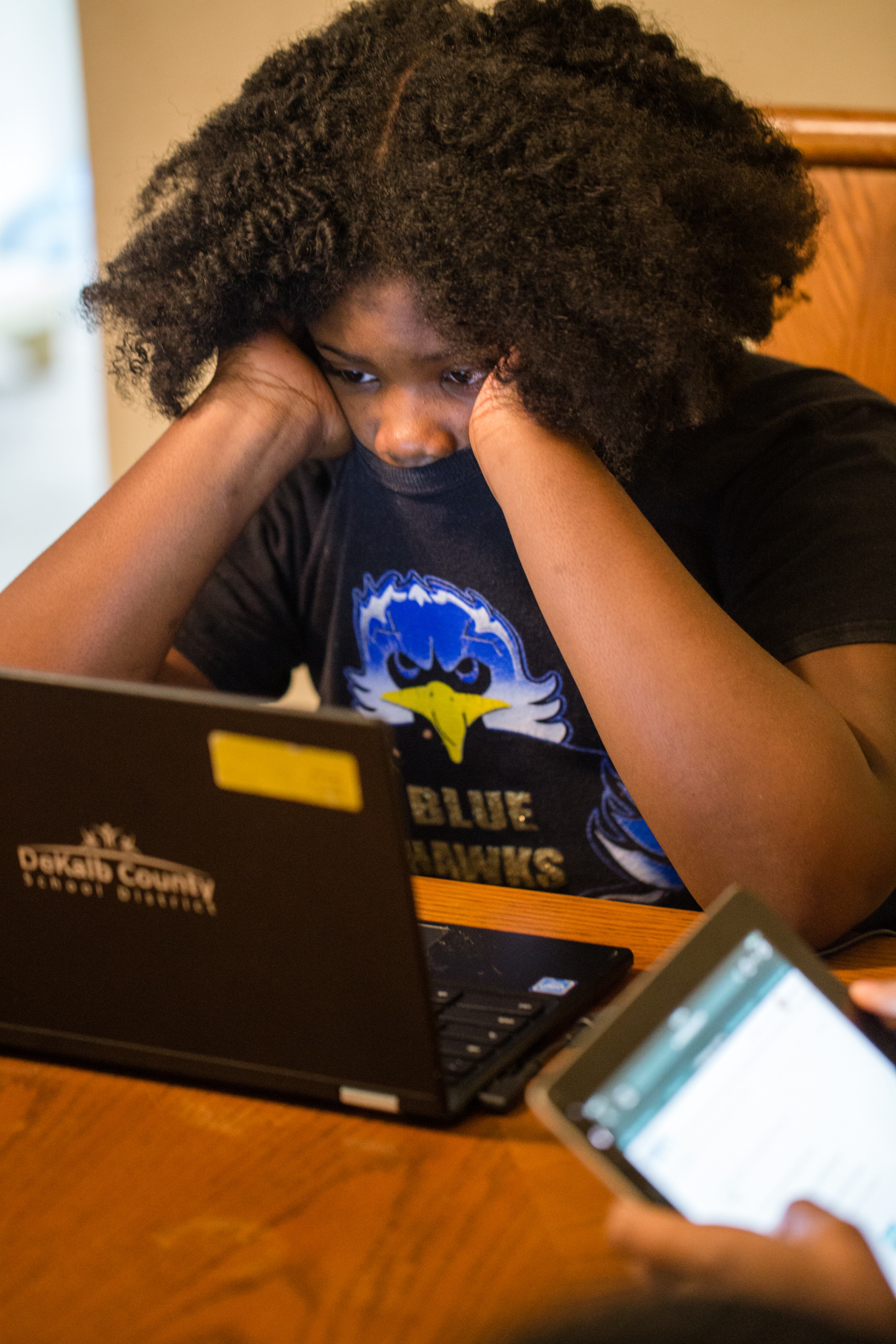

The data raises serious questions about the effectiveness of distance learning, particularly among low-income families where classroom time and school lunch programs are seen as imperative to quality education.

Most of those 100,000 pupils — which represent 1-in-5 students from the region’s largest districts, including Cobb, DeKalb, Fulton, Gwinnett counties and Atlanta Public Schools — have likely never logged into school online learning systems because of connectivity issues and inequity of access to the electronic devices, officials from several major school districts say.

“The complexity of digital learning is multifaceted,” DeKalb County Superintendent Ramona Tyson said. “It’s about the digital divide of the haves and the have nots. It’s about the connectivity in the home. Through no fault of their own, every student doesn’t have a device.

“We’ve got work to do to address that.”

The districts are trying.

A fundraising effort to buy laptops and high-speed internet access for low-income Atlanta Public School students raised $350,000, but Superintendent Meria Carstarphen has said the full cost to fill that need is closer to $1.5 million. And most districts have attempted to reach some students by passing out paper assignment packets or sending home emails to parents about continued expectations.

Gauging how much learning is being done at home is difficult because the state is not tracking log-in rates and the school districts keep track in varying time frames, some every week and some every day.

District officials, though, claim the overall percentage of students who do not log on has not wavered.

Kevin Wu, chief executive officer for the online student resource center OneClass, said digital learning challenges go beyond just technical. It will take time for schools, teachers and students to adjust to a new normal, he said.

“People associate (learning) with being in a physical classroom,” Wu said. “All of a sudden, everyone is expected to have that same level or passion for learning in another environment. It’s a mental challenge a lot of students have to get over.”

A recent poll by Wu’s company surveyed about 1,300 students across the country, with just over 75% of them saying they do not feel they are getting a quality learning experience since schools went totally online.

Aside from access to internet and adequate devices, students were concerned with teacher technological proficiency.

“It affects how students feel about the overall experience,” Wu said. “A lot of teachers are just going through their regular lectures … and it’s a one-sided experience.”

State regulators waive attendance mandates

Difficulty with online access extends to the districts themselves.

School systems found out immediately that companies operating digital learning portals lacked the bandwidth to allow millions of children across the world access at the same time. The first few days, students found themselves unable to log in as portals hit their limits.

Other issues included low internet speeds as well as systems not having video available to either upload or broadcast live to students. Many districts have added other providers like Zoom and Google Classroom to give teachers multiple resources through which to reach their students.

Online learning portals were designed as a short-term alternative when the traditional classroom setting is not available. Until mid-March the portals were used sporadically, mostly when inclement weather kept students out of school.

State regulators have waived attendance mandates since teaching moved online, knowing the information received from digital log-ins was less reliable than counting heads in a classroom. Log-in attendance became even more of an issue when districts were forced to utilize multiple digital platforms because of connectivity issues.

Sandy Rogers said her son, Landon, had problems with Cobb County Schools’ online learning set up.

Landon, who attends Floyd Middle School in Mableton, is on an Individualized Education Program, which is designed to give him extra time on assignments and a co-teacher by his side as he goes through lessons. Initially, that was not part of the online experience.

“They were giving him stuff that was not on his reading level, and he only had me to learn with,” Rogers said. “He learns a different way from how I learn, or how my older daughter learns. The first four weeks were miserable.”

Landon also was using his sister’s laptop, because he did not have one of his own and Cobb was prioritizing devices for high school students, Rogers said.

A lack of bandwidth in the morning led to them starting school work at 6 p.m., according to Rogers. Lately, Landon’s teachers have been using Zoom to reach him, walking him through lessons at a pace he can handle.

“It’s been better lately, because he’s got his teachers with him,” Rogers said. “Before now, I would go to sleep at night wondering does he have (the lesson)? Will he remember it?”

Working in shifts

Some districts have announced plans to grade students based on the work they did in class through March 13.

DeKalb County School District, in announcing the school year would end about a week early for most students, said digital learning work would be used only to help improve grades posted before schooling moved online.

“I feel like teachers should only enforce (digital learning) for students who need it,” said LaTonya Hill, a former DeKalb Schools teacher who has four girls in the system.

When schools went fully digital in March, Hill said she had one laptop for her girls to share. She said she has since purchased additional devices so her daughters don’t have to complete school work in shifts.

“They’re doing their work, but it has been a lot,” Hill said. “For parents who don’t have technology, it’s hurting their children. For parents who don’t understand and can’t really help their children, it’s not working.

“My kids are lucky, but others, not so much.”

Clayton County Schools officials did not provide the log-in rates for their students. A records clerk responded to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s request by saying the data was kept by the individual schools and that collection would be “voluminous and time consuming.”

About 86% of Gwinnett County’s 178,000 students are logging into the district’s main online learning platform daily — leaving about 25,000 students out of daily activities. The percentage of students logging in is down from 97 percent during the first two weeks of the shutdown.

When school buildings are open, the district boasts attendance rates well above 90 percent daily. Officials are working to issue Chromebooks to students where low participation is attributed to a lack of access.

About 4,000 devices were distributed in one week recently, Gwinnett County Schools spokeswoman Sloan Roach said.

“The checkout program is designed to assist families identified as having the most need first,” Roach said.

In Cobb County Schools, which serves about 110,000 students, district officials said teachers are using multiple online platforms. Attendance has been affected there, too, with about 18,000 students unaccounted for every day in the digital learning realm.

“Our teachers use the platforms which works best for them,” a spokeswoman said.

Just under two-thirds of DeKalb County School District’s 99,000 students are logging into the district’s primary online learning platform Verge, but some teachers pivoted from the platform early on after finding trouble logging in or being unable to access everything they needed. Some are now using different platforms, including Google Classrooms, which do not all deliver access rates to school officials.

Tyson, the DeKalb superintendent, said paper packets are made available to students who don’t have access to the needed technology, with some principals and teachers delivering assignments in person. The district also has given out a number of devices to aid students with logging in.

The district’s students in grades 6 through 12 have devices. Most from Pre-K through grade 5 do not. It shows in the numbers. While 71% of those in grades 6 through 12 are logging into the district’s main online system regularly, about 46% of the district’s kids in grades 5 and below are not.

DeKalb parent Tywanna Bailey-Britt said she was thankful when her son’s teacher reached out to her about a week after learning went online. It was early on, and the teacher found Google Classroom works better.

“They walked me through the process and he’s able to do his work now,” she said. “What about parents who don’t know? I’m going to be an advocate. You can’t retain a child (over this).”

Less than half of Fulton County Schools’ 94,000 students are logging in daily to the district’s ClassLink online learning portal, though district officials said high school students have other portals through which they are completing assignments that do not keep track of log-in and other access information.

The district has issued about 65,000 laptops, including several thousand purchased since school buildings were closed.

Students also are receiving paper work packets, at a rate of about 1,000 per grade level per week. Parents also should be receiving emails with information about the work expected from students, officials said.

Aside from traditional lessons, some students are also getting online lessons on things like anxiety, fear and resiliency.

“I had a student the other day who said she was afraid to go outside,” said Pam Whitlock, a teacher at Chattahoochee High School and Fulton County Schools’ 2019 teacher of the year.

She said she calmed the student down by giving her a tour of her own home. Whitlock’s husband waved to the girl, they looked around the backyard and also found Whitlock’s Wheaton terrier, Jax, sitting on a pile of clothing in the laundry room.

“You’re not really trained how to handle a situation like this,” Whitlock said, “because it’s so strange and so unusual.”

Reporters Ben Brasch and Kristal Dixon contributed to this story.