Rural schools work on Georgia’s reading problem

During a drive through South Georgia this spring, David Berggren’s son said something that stunned him.

The first grader was fiddling with an iPad in the back seat, where he was sitting with a classmate. Then, the pair started debating who did better on the school reading tests.

“Their discussion went along the lines of ‘well, I’ve read this many books, I’m going to get a reading award,’” Berggren said. “What surprised me was the competition.”

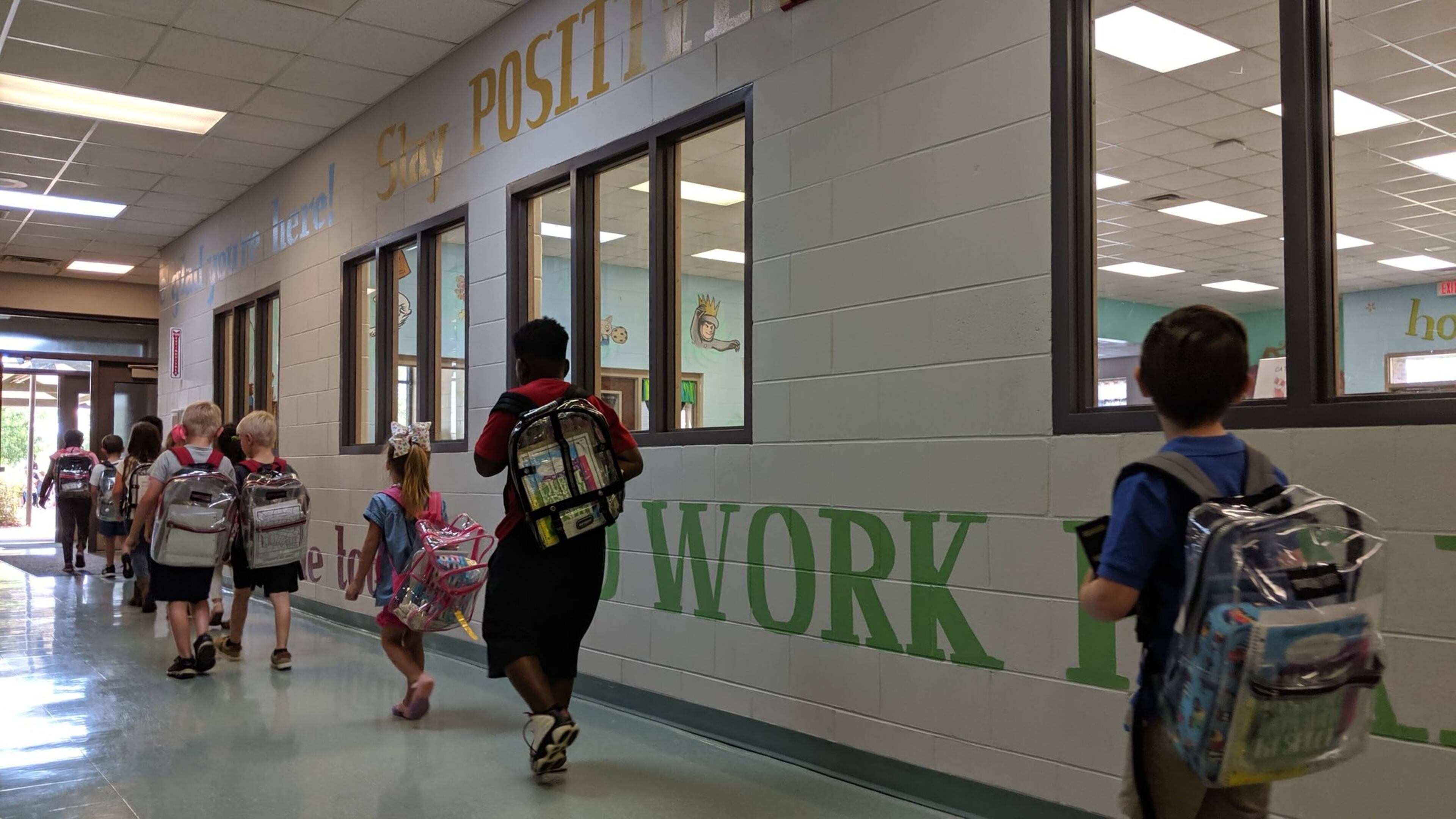

The boys attend Sunset Elementary School, about three hours southeast of Atlanta, where third grade reading scores have been climbing since 2016. That’s when a new principal took over, and began using special testing and teaching materials. Sunset already had the tools, which the Colquitt County School System had acquired with a state grant. But teachers were not using them effectively.

“They didn’t understand how to use the data,” said the principal, Josh Purvis.

The Moultrie school's rising reading scores are a promising development in a state where just over a third of students in third grade test on grade level in English Language Arts. Poor literacy at that age, when reading becomes crucial, undermines later academic performance, stalking students into high school and beyond. The recent adoption of a landmark Georgia law on dyslexia — a condition that inhibits reading — was driven by concerns about reading; the new law requires mandatory screening of every kindergartner starting in 2024.

Sunset’s average third grade Lexile score, a nationally recognized measure of reading ability, trailed the state by more than 80 points in 2015. By 2017, it had nosed past the state. In 2018, it was nearly a dozen points ahead, at 672. That’s despite a higher-than-average proportion of students from economically distressed households.

Sunset’s experience suggests a way forward. The combination of a leader with a deep background in literacy — Purvis did his dissertation on the topic — and money to buy special diagnostic and teaching tools appears have to paid off. “Their children are receiving strong instruction supported by a leader who understands the data,” said Julie Morrill, literacy program manager for the Georgia Department of Education.

Purvis implemented an intricate tracking system for each student, using tools that measure reading skills well before third grade, when state testing starts. Other schools without those tools can only guess how well their youngest students are doing. He trained the teachers and established a new policy: For the first half-hour of each morning, they get “sacred” and “guarded” time to teach reading basics. The children are split into different classrooms based on their ability, so it’s easier to teach them at their level.

Why aren’t more schools doing this?

Leaders need training, and so do teachers. And, due to the decentralized nature of the state’s education system, each of the 180 school districts runs its own affairs. Local leaders dictate how to teach local children to read, and how much money to spend on it.

And there is a shortage of money.

Sunset was among about 160 elementary and primary schools that won some of a $115 million federal “striving readers” grant for Georgia. That’s in a state with 1,300 elementary schools.

Worth County Primary School, 40 minutes to the north, also won some of the money, spending it in much the same way. Students at the K-2 school in Sylvester take baseline reading tests in the fall, and their progress is checked in December and May.

On a recent afternoon, first graders were getting tested on phonics. They had to pronounce random letter clusters — nonsense words — while a teacher timed them. Then, they read a paragraph of real words, as a teacher checked their “fluency,” or reading pace.

The page said “basket” and a boy read “biscuit”; it said “large” and he saw “ledge”; when he came to “Africa,” he read “America.” He was mid-paragraph when the timer ran out.

“Did I do good?” he asked.

Despite his stumbles, he had exceeded the minimum number of correct words.

“You did,” she told him.

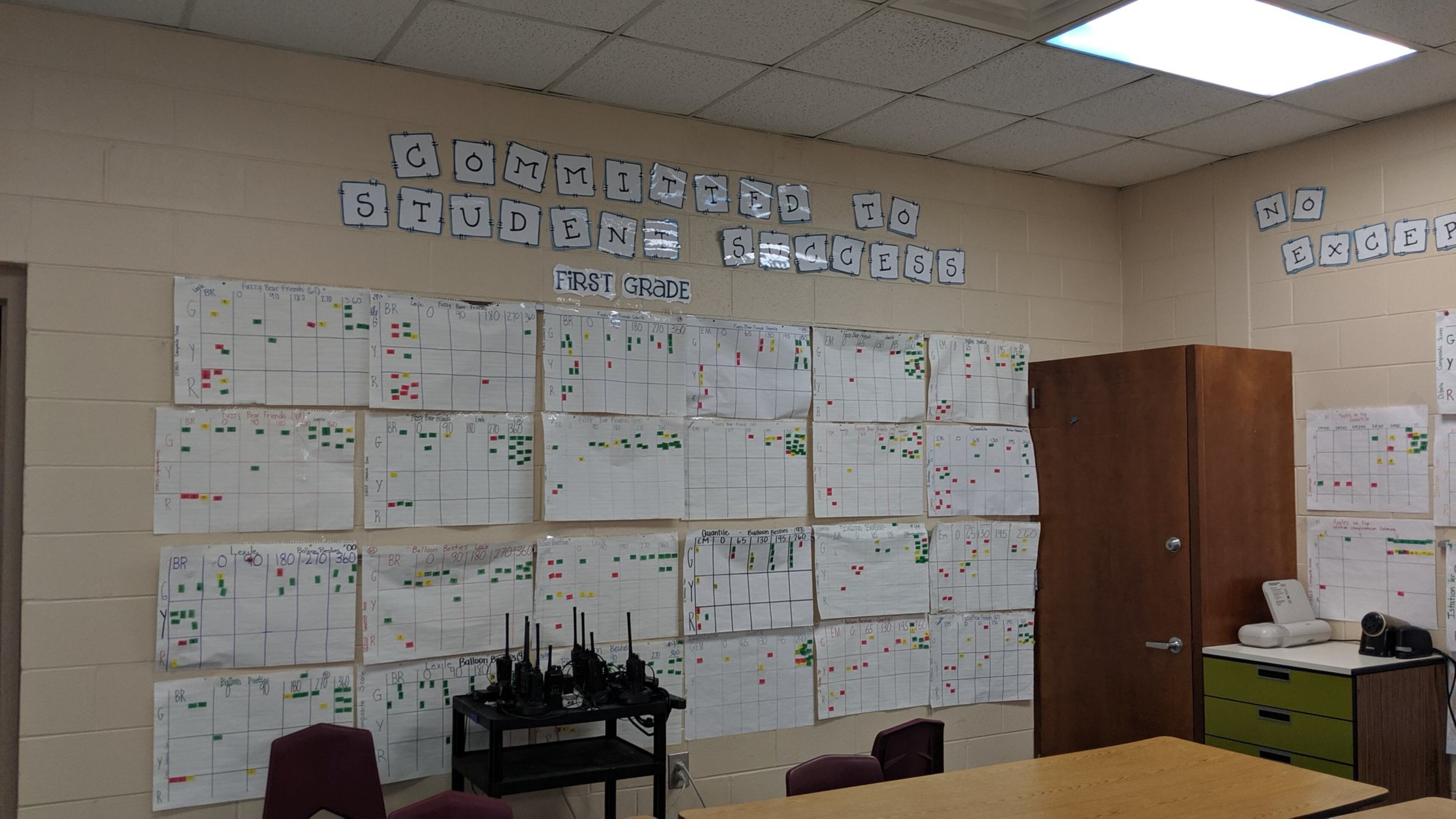

Principal Jared Worthy has been using charts to track each student’s progress. Each fall, incoming students get a Post-it note color — red, yellow or green — based on their first tests in the fall. They are placed on a corresponding row on a chart, and they advance up and to the right as their scores improve.

The rising third grade scores on mandatory state tests at the nearby third through fifth grade school, Worth County Elementary, suggest something good is happening at Worthy’s primary school. He asked why, if the research shows so many students in third grade aren’t on grade level, more money isn’t flowing to the earlier grades, so more schools can do what he’s doing.

“We’re expected to build the firm foundation with nothing,” he said.

But money isn’t enough; schools need leaders who can use it well. Before Purvis arrived at Sunset Elementary in Moultrie, teachers were using the tests and curriculum, but they weren’t systematically tracking the students. That meant they weren’t giving each child the right help. Purvis likens it to going to a gym to build biceps but only working out with the legs.

Like Worthy at Worth Primary, Purvis has a room filled with charts that bristle with red, yellow and green Post-it notes.

Lori Ward, who teaches kindergarten there, said teachers were collecting the test data before Purvis came. But they had to figure out how to teach each student at his or her own level, in a classroom with lots of levels. “It was just a lot of work on us,” she said. Things are more “structured” now, she said. “Instead of just the teacher doing things, you have the leadership helping you carry it out.”

The Georgia Department of Education has recruited Purvis to speak at conferences about what his teachers have accomplished, deploying him as a sort of evangelist for early childhood literacy.

But the supplemental federal dollars to help pay for reading have dwindled. After the striving readers grants expired a couple of years ago, Georgia was awarded another round of funding, and got more than any other state: At less than $62 million, it’s half of what Georgia got the last time.

BY THE NUMBERS

The average Lexile* scores for Sunset and Worth elementaries’ third graders surpassed the state’s a couple of years ago, according to data from the Georgia Governor’s Office of Student Achievement:

School year: 2014-15; 2015-16; 2016-17; 2017-18

Sunset Elementary: 556.4; 602.9; 667.2; 672

Worth County Elementary: 588.9; 599.6; 668.9; 668.1

State: 639.2; 653.8; 664.7; 660.3

* The Lexile Framework for Reading is based on research funded by the National Institutes of Health. It is used to measure students’ reading skills and to set ranges for grade levels. It also is used to score books, so readers can be paired with texts at their level.