‘We had to stop the bleed’

In the summer of 2016, Princess Loyal transferred to Gideons Elementary School, hoping to have a better classroom experience. The year before, the second grade student had faced dysfunction at her previous school. Teachers shouted at students. Sometimes, Loyal shouted back. Things worsened to the point where the only way educators let Loyal finish that year was if her grandmother, Queen La’Rosa Harden Green, accompanied her to school.

Green, a longtime resident of Atlanta’s Pittsburgh neighborhood, feared the experience might cause lasting harm. But at Gideons, Loyal received more one-on-one attention. Teachers treated her respectfully. Loyal grew fond of her third grade teacher. Soon, her behavior improved — aside from the occasional curse word. She thrived in school.

“She was very focused on her lessons,” Green said. “She was on the honor roll.”

Over the past decade, the Atlanta Public Schools cheating scandal devastated Pittsburgh. The community's schools were at the epicenter, so much so that one will be the focus of a forthcoming Hollywood movie. For a proud South Atlanta community once home to one of the city's best schools for black children, the memory of teachers marched out of school by police still stings. So much so that when a group of residents this past winter were asked to identify the topic they would like to see covered about their neighborhood, they asked for a story about how Pittsburgh children were faring at school four years after the trials.

As part of the Pittsburgh Journalist Project, three citizen journalists tackled the story of the recovery efforts as part of the program to broaden and diversify news coverage of their community.

In the course of their reporting, they learned that improving the lives and academic performance of students in Pittsburgh is much more difficult than just dealing with the consequences of widespread cheating. Providing help for those who missed opportunities because their test scores were inflated is not enough; solutions must reach all students, and address the underlying challenges that tempted administrators to cheat in the first place. Solutions being implemented include not just academics but also family engagement, quick interventions for in-school problems, and additional resources for students who fall behind in school.

So far, the ambitious APS effort is promising, despite some early disappointments — including ones that have revealed the difficulties that come with helping students most impacted by the cheating scandal. But the early progress has made residents like Green hopeful that Pittsburgh’s children will get the academic resources needed to help their community fully thrive again.

"Some of the kids have been put in a better situation," said Columbus Ward, chair of Neighborhood Planning Unit-V, which includes Pittsburgh. "But some of the kids became more disconnected from the broader part of the school system, and have been discouraged from being in a learning atmosphere."

***

One of Atlanta’s oldest black communities, Pittsburgh has had access to strong schools for over a century. In the early 1920s, Clark College, Clark Atlanta University’s predecessor, donated land for a school at the corner of West Avenue and Fletcher Street. Named after Clark’s first black president, the William H. Crogman School became known as “one of the best and most attractive schools” for black students in the city, according to the National Register for Historic Places. Crogman’s educators — which included members of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s family — taught students who became politicians, professional athletes, law enforcement officers, and doctors.

Local officials built two more schools, Gideons Elementary and Walter Leonard Parks Middle School, during the civil rights era. But between 1960 and 1980, Pittsburgh’s population dropped from nearly 10,000 to 4,300, in part because of more affluent residents left the neighborhood. The Crogman School, once the pride of Pittsburgh, closed. Remaining residents, many of whom were seniors, watched as drugs, crime and the sex trade took over the neighborhood. Positive opportunities dwindled for children there.

» RELATED | A timeline of how the Atlanta school cheating scandal unfolded

Soon, Gideons and Parks would become tainted by scandal. Faced with No Child Left Behind, the federal policy that penalized low-performing schools that didn’t make fast enough testing improvements, APS leaders pressured teachers to boost test scores — no small feat in a community where children faced the forces of poverty, crime and disinvestment. In the 2000s, some Pittsburgh teachers systematically changed test answers from wrong to right. Unsurprisingly, higher test scores followed.

Later that decade, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution found APS test score irregularities, prompting a state investigation. Of the dozens of employees arrested, seven educators at Parks and Gideons pleaded guilty. After a sensational trial, Fulton County jurors found 11 educators guilty on charges related to their involvement in the scandal. Among them was Michael Pitts, the district administrator responsible for Parks Middle School.

In the midst of the scandal, Parks closed its doors — replaced by Sylvan Hills Middle School — and its alumni struggled to escape shadow of the scandal. Esha Daniel, 23,a former Parks student who attended Carver Early College, earned a social work degree from the University of Georgia. While some UGA students felt she had overcome adversity, Daniel said, others questioned her academic ability.

APS Superintendent Meria Carstarphen replaced Beverly Hall, who before her death in 2015 faced criminal charges for her role in the cheating scandal. In Carstarphen's early years on the job, she acknowledged the 52,000-student school system had lost sight of its "core purpose" of focusing on children. So officials crafted an ambitious systemwide plan that would fix two things for Pittsburgh: overhaul how students learned at Gideons Elementary, and help former Parks students catch up in school.

"You can't talk about the future," Carstarphen said in 2016, "if you don't fix the past."

***

The first time incoming principal Danielle Washington stepped inside Gideons, the year after the APS cheating trial ended, the challenges seemed daunting. Nearly half of the students who attended the year before were no longer there. Among those who remained, reading proficiency levels stood in the single digits. Four out of five fifth graders couldn’t pronounce all 26 letters of the alphabet.

"I want students to leave here prepared to know excellence, and I want people who see them to say, 'Oh, that student went to Gideons.'" — Danielle Washington, principal, Giddeons Elementary School

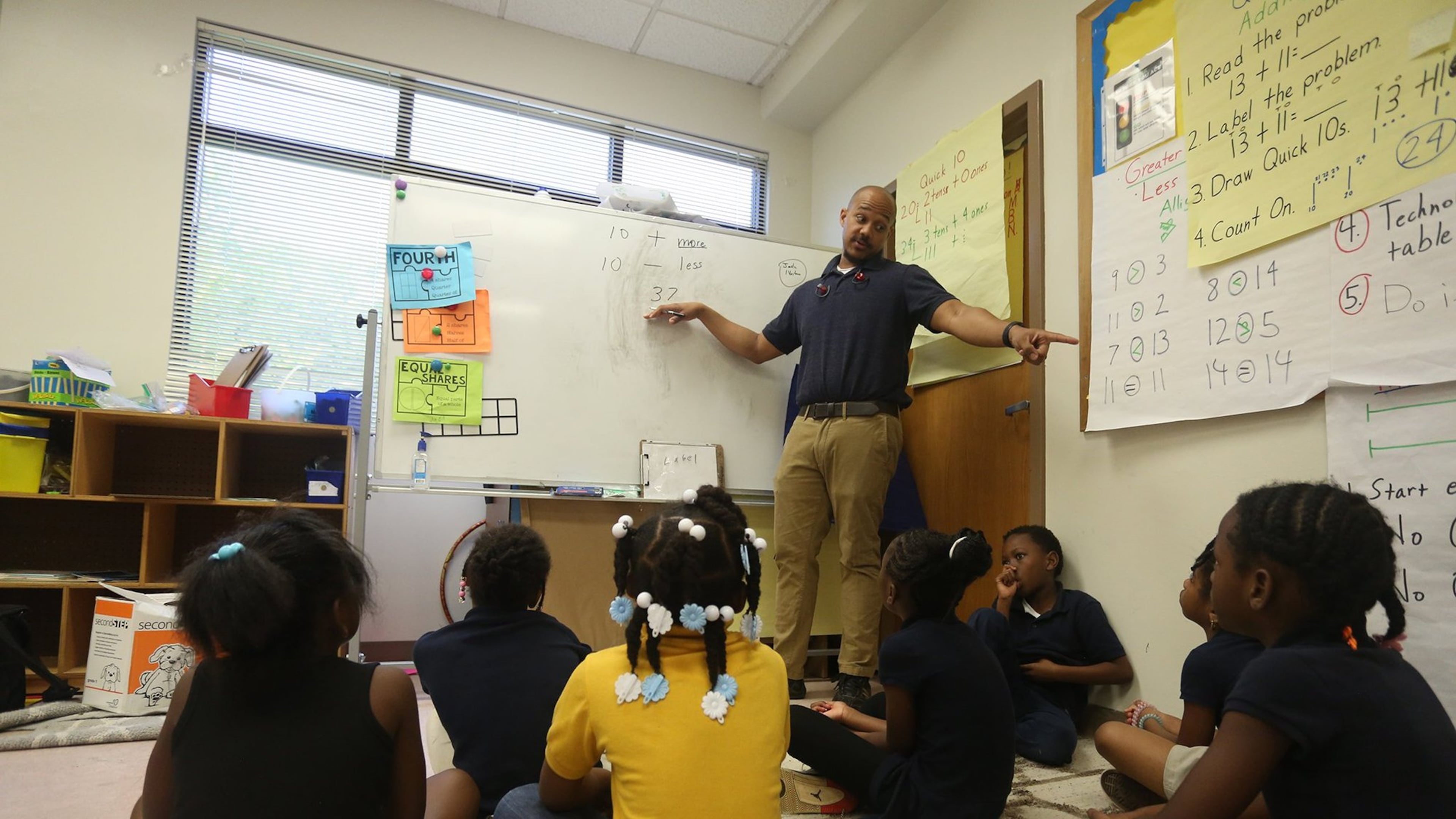

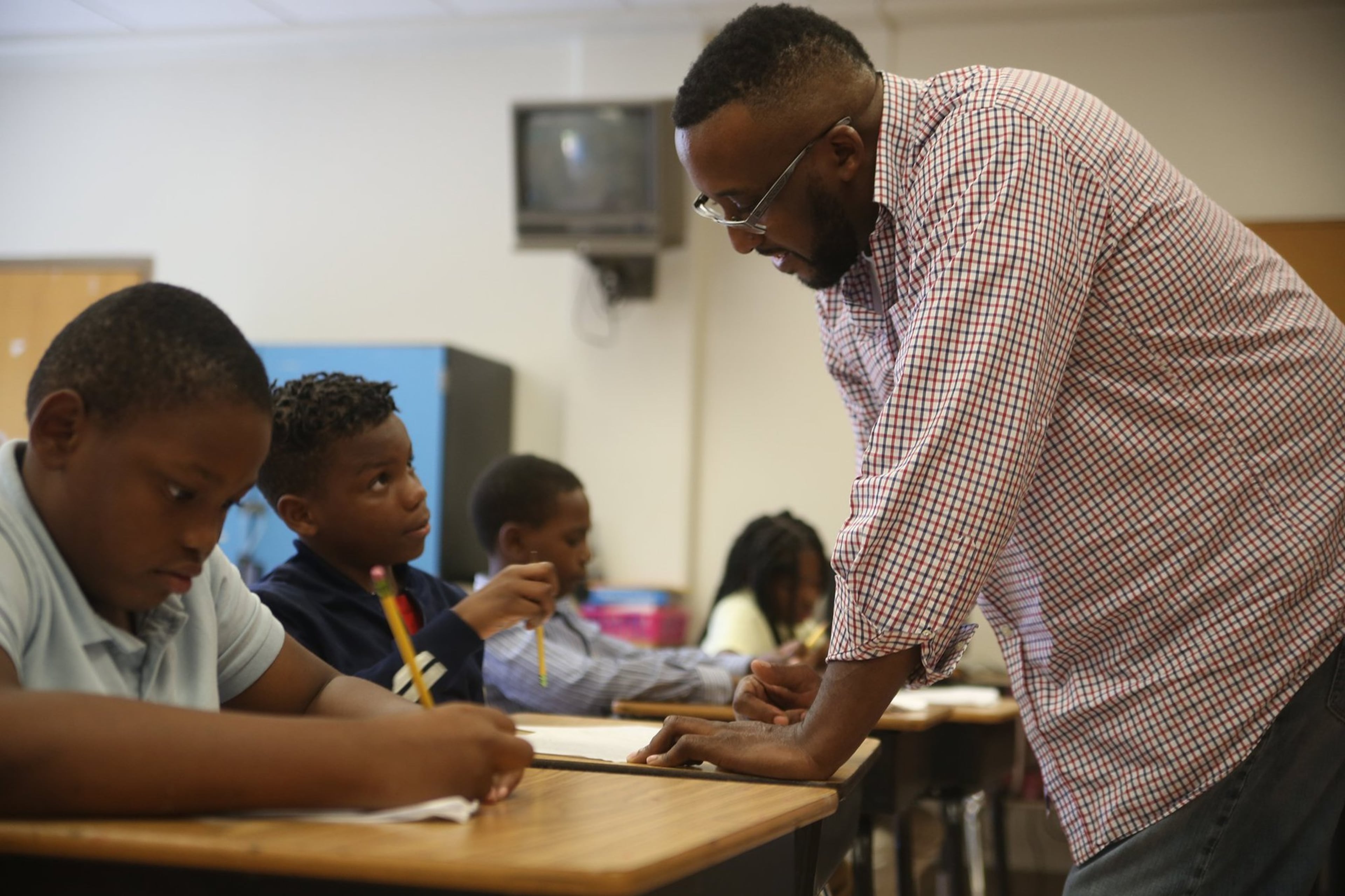

As part of the APS turnaround strategy, charter school operator Kindezi assumed operations in late 2017. As principal, Washington spent her first three weeks getting students to understand the basics of lining up in the hallways, and setting expectations for how to behave in class. Her staff also incorporated lessons on skills like conflict resolution and emotional coping.

Eventually, Washington said, students like Loyal started to “see the fruit of those lessons.” They received more personal attention, and more access to after-school programs. That first year, Washington instructed educators to teach 40 more minutes of reading a day to help students close the literacy gap.

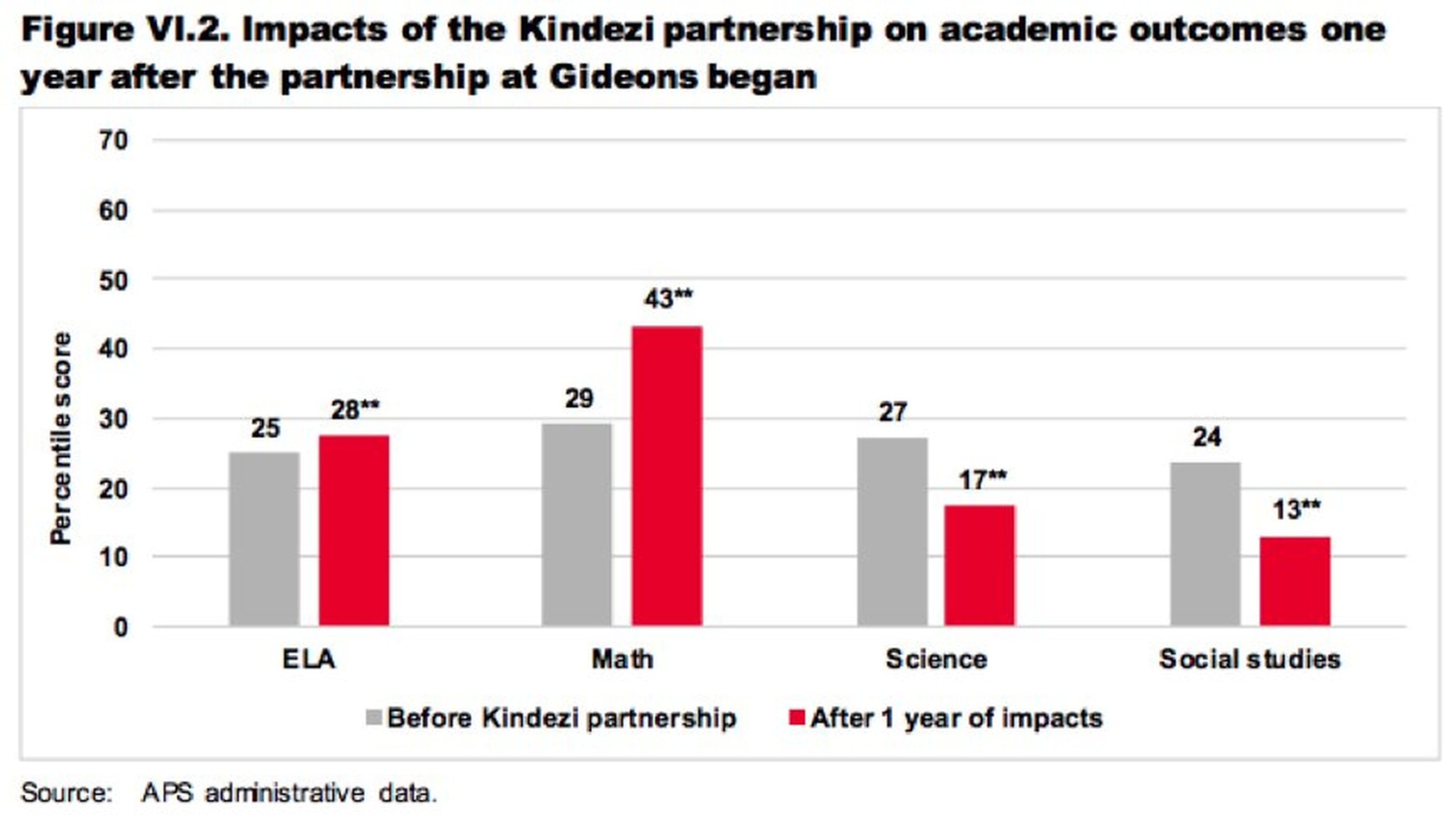

While Kindezi’s intense focus on reading paid off — Gideons improved English scores — students received fewer social studies and science lessons. Students regressed in those test scores, according to researchers tracking the APS turnaround progress. More science and social studies class time will be reincorporated into the upcoming school year’s next year’s curriculum.

“We had to stop the bleed,” Washington said. “Now we can get them proficient in other areas.”

Months after the APS trial ended, school officials launched the Target 2021 program, a $14 million systemwide effort, which began with identifying roughly 3,000 students impacted by the cheating scandal. Atlanta Councilmember Matt Westmoreland, a former Carver teacher and APS board member, says students were offered services such as individual counseling, SAT prep, tutoring, college and career fairs, and parent workshops.

But the efforts didn’t work for everyone, and some Pittsburgh students say they never got the full help needed to thrive in school.

One of those students, Dijon Brunson, now 23, remembers the day when the police escorted his teachers out of Parks. He didn’t understand the gravity of how the teachers’ dishonesty in secretly changing test scores hurt students until he struggled on his tests at the end of eighth grade. The following year, he continued at Carver High School. Teachers made him feel “stupid,” he said. He felt “disheartened” without adequate support. During his junior year, he dropped out. He never received his diploma.

Other students impacted by the cheating scandal ultimately spent time in APS alternative schools like Forrest Hill Academy and Alonzo A. Crim High School. Diamond Coats, who attended Gideons during the cheating scandal and later went to Crim, worries she was deprived of a full education.

“They need to teach us about things that’s going to get us further in life,” Coats said.

“It’s a fact that much attention was given to students that were affected by the cheating scandal,” said Deanna Rogers, APS remediation and support coordinator. “At the end of the day, their goal is to get them graduated.”

To do so, Rogers said the initiative aimed to reduce the course failure rate and increase the graduation rate. While the graduation rate has increased, Georgia State University researcher Tim Sass found that Target 2021 has had a minimal impact on attendance, grades and test scores. Sass also found the initiative had “no impact on the likelihood of graduation” and “either no impact or a negative effect on the likelihood of attending college within one year of graduation.” Despite those findings, APS spokesperson Seth Coleman said the program still had a “positive impact” on students — citing a satisfaction survey taken by 109 parents who felt their children benefited from the Target 2021 services.

"All of us could have done more," Westmoreland said. "It's up to the school system to provide as many resources available as possible to help these students."

***

From Kindezi’s second-floor administrative office, just above where Gideons parents pick up their kids, Washington recognizes her students need more than just hands-on coursework. That’s why Kindezi has sought to not only care for the students but their entire families.

Listening to her radio scanner, Washington lists how the school works to make families whole. Educators at Kindezi and APS have bolstered after-school tutoring services, and made available tablets and computers during class to students whose parents can’t afford electronic devices. Her team also fires off automated text messages to parents so they can be kept informed about the progress of their children at school. If problems arise, teachers meet with their students’ guardians to create an action plan. One Gideons staffer even recalled a teacher driving to pick up a student who missed the school bus.

Beyond that, APS allows social service providers to operate inside Gideons. LaKeta Whittaker, a Pittsburgh resident who works as an Atlanta Volunteer Lawyers’ Foundation community advocate, provides resources and educational materials to reduce housing instability for families in the area. Because of Kindezi’s flexibility as a charter school operator, Washington created a policy allowing students to stay at Gideons, even if their family is displaced from Pittsburgh. According to Washington, school turnover has dropped from nearly half to around 30 percent since her first day at Gideons.

Green, Loyal’s grandmother, says her family has felt the heartfelt embrace of Kindezi. Early on, Gideons referred Loyal to for counseling related to her behavioral issues. After steady progress, they discontinued counseling in part because of the improvements. Seeing how they cared for Loyal, Green felt inspired to be more engaged at Gideons. As educators slowly rebuild trust, Green feels like everyone involved is focusing more on what matters most: the children.

In a few weeks Loyal, who's entering sixth grade, will head to the Coretta Scott King Young Women's Leadership Academy, a Westside STEM school. For Washington, the work continues. Instead of teaching students in a temporary location — the former Parks Middle School — Kindezi educators will hold class at the original Gideons campus, which had undergone a $16.5 million renovation. Washington will be there to greet them inside a school designed to be "bright, light and gorgeous." Like the school's aesthetic, Washington believes students will someday shed the shadow cast by APS' darker days. When that happens, they'll no longer be seen as victims of a past scandal, but as students with a future.

“I want students to leave here prepared to know excellence,” Washington said. “And I want people who see them to say, ‘Oh, that student went to Gideons.’”

About the Pittsburgh Journalism Project:

The Pittsburgh Journalism Project is a media training initiative that seeks to improve the quality of local journalism by having experienced journalists partner with community members to produce more relevant and representative stories. Pittsburgh previously had no journalist of its own. And journalists from outside Pittsburgh often focused on the community's deficits — mortgage fraud, crime, displacement — instead of painting a fuller picture of life there. So the PJP asked 10 residents to weigh in on what stories they'd like to see covered in their community. Their top choice: A story that looked at how Pittsburgh children are faring in school four years after the APS cheating trial ended. From there, the PJP paid three residents with writing and research experience to learn how to report and write a news feature. The hope is that, once this training ends, these community journalists will have the tools to keep telling stories about Pittsburgh. — Max Blau, founder of the Pittsburgh Journalism Project. (Contact us at pittsburghjournalismproject@gmail.com.)

About the authors:

Braddye Smith, a native of Pittsburgh, is a supervisor with DeKalb County government, managing cases for an accountability and diversion court. Since her teenage years, she has enjoyed writing poetry.

In her professional life, she writes training manuals for the positions in her office, pulling from her deep knowledge of criminal justice. She hopes to challenge herself by learning about the field of journalism and to gain professional writing skills. By becoming a community journalist, she wants to be a positive voice for the Pittsburgh community, which will allow readers to obtain complete, accurate and unbiased news from an invested resident. Her daughter graduated from Carver Early College in 2013.

Chandra Harper-Gallashaw, who lived in Pittsburgh for over a decade, spends her days working as a community leader and a researcher at Georgia State University. She believes the journalism training will help her in the process of writing a memoir. By becoming a community journalist, she hopes to find a way for people in Pittsburgh, where her daughter now lives, to shed light on the positive parts of the community.

William "Mr. Bill" King, who has lived in Pittsburgh for about 30 years, has been involved with almost every neighborhood organization from the Civic League to the Pittsburgh Neighborhood Association. He wrote for a couple of college newspapers and the Pittsburgh Master Plan newsletter. He is currently working on a book about his life and more importantly about Jesus, what William thinks is going on in the world today, and what we might do about it. He hopes this experience will help tell the Pittsburgh story while honing his writing skills.